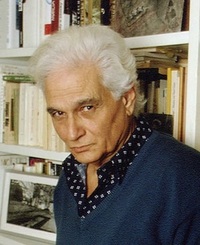

Jacques Derrida (1930-2004)

I will actually start making the argument on Monday

Jacques

Derrida (1930-2004)

is perhaps the closest thing to the major voice of postmodernism. If

we were to try to sum up in one sentence a single idea emblematic of

postmodernism we could not do better than to say postmodernism is the

view that three are no meta narratives. Derrida, working in the

philosophical

heritage of Edmomnd Husseral. “Given this ontological

critique, which Derrida claims pervades all of western philosophy,

Derrida asserts a sort of post-metaphysical, post-foundational,

perspective of reality that is not so much a new philosophy, but

rather one that no longer naively accepts the arbitrary metaphysical

claims of western thought.”[1] Derrida holds that western

thought has always assumed

a logos, or a transcendental signified. “For

essential reasons the unity of all that allows itself to be attempted

today through the most diverse concepts of science and of writing,

is in principle, more or less covertly, yet always, determined by an

historico-metaphysical epoch of which we merely glimpse the

closure.”[2]

Rather

than seeking to destroy all truth he seeks to show that the modern

metaphysical referents to which the assumptions of logos pertain are

inherently problematic.

To explain the meaning of the transcendental signified with reference to the article itself as well as my previous understanding of this concept, I can say that Derrida assumes that the entire history of Western metaphysics from Plato to the present is founded on a classic, fundamental error. This error is searching for a transcendental signified, an “ external point of reference” ( like God, religion, reason, science….) upon which one may build a concept or philosophy. This transcendental signified would provide the ultimate meaning and would be the origin of origins. This transcendental signified is centered in the process of interpretation and whatever else is decentered. To Derrida THIS IS A GREAT ERROR because... 1. There is no ultimate truth or a unifying element in universe, and thus no ultimate reality (including whatever transcendental signified). What is left is only difference. 2. Any text, in the light of this fact, has almost an infinite number of possible interpretations, and there is no assumed one signified meaning.[3]

For

Derrida, as

with Davies,

there is nothing outside of the realm of signifier

that we can latch onto and pull ourselves out of the

quagmire of signs and signification. There is no touchstone of

meaning outside of that realm

because all meaning is

based

upon the shifting sands of signifier and differance.[4] So modern though is between a

rock and a

hard

place. We are either trapped in the world of signification where

meaning is arbitrary and always differed to the next signifier which

is also arbitrary, or we are stuck in the Cul-de-Sac

of scientific reductionism.

Jacob

Gabriel Hale asserts

that Cornelius Van Til (1895-1987) has the answer. Van Til was a

Philosopher and Reformed Theologian best known for the transcendental

Argument for God (TAG).[5] Hale

compares Derrida to Van Til. Both understand modern thought to be

trapped in the same dead end seeking a logos but unable to connect

with

it. While

Derridia's answer is to give up on logos and tear down hierarchies

and be stuck like a character in a Becket play, Van Til understands

God as the true presupposition to logic.[6] Thus Van Til fills in the blank of the logos with the Christian

Logos. The

Christian intellectual tradition has always regarded God as the basis

of logic

probably going back to the Greeks and their idea of logos. It's a

concept very reminiscent of St. Augustine in his association of God

with truth.

Augustine

expresses the concept of the super-essential Godhead many times and

in many ways. Augustine was a Platonist. In that regard perhaps his

greatest innovation was to place the Platonic forms in the mind of

God. That is a major innovation because it trumps the Neo-Platonistic

following after Plotinus, who conceived of a form of the forms. In

Augustinian understanding the equivalent of the “the one” the

form that holds all other forms within itself is the mind of God.

Augustine never made an argument for the existence of God because for

him God was known with certainty and immediacy. God is immediately

discerned in the apprehension of truth, thus need not be “proved.”

God is the basis of all truth, and therefore, cannot be the object of

questioning about truth, since God is he medium through which other

truths can be known.[7] Paul Tillich reflects upon Augustine’s concept:

Augustine, after he had experienced all the implications of ancient

skepticism, gave a classical answer to the problem of the two

absolutes: they coincide in the nature of truth. Veritas is

presupposed in ever philosophical argument; and veritas is

God. You cannot deny truth as such because you could do it only in

the name of truth, thus establishing truth. And if you establish

truth you affirm God. “Where I have found the truth there I have

found my God, the truth itself,” Augustine says. The question of

the two Ultimates is solved in such a way that the religious Ultimate

is presupposed in every philosophical question, including the

question of God. God is the presupposition of the question of God.

This is the ontological solution of the problem of the philosophy

of religion. God can never be reached if he is the object of a

question and not its basis.

Augustine says God is truth. He doesn’t so much say God is being as

he says God is truth. But to say this in this way is actually in line

with the general theme we have been discussing, the one I call

“super-essential Godhead,” or Tillich’s existential ontology.

Augustine puts the emphasis upon God’s name as love, not being.

Since he was a neo Platonist he thought of true reality as beyond

being and thus he thought of God as “beyond being.” This makes no

sense in a modern setting since for us “to be” is reality, and to

not be part of being would meaning being unreal. But in the platonic

context, true reality was beyond this level of reality and what we

think of as “our reality” or “our world” is only a plane

reflection of the true reality. We are creatures of a refection in a

mud puddle and the thing reflected that is totally removed from our

being is the true reality. It was this distinction Tillich tried to

preserve by distinguishing between being and existence.[8]

Augustine

looked to the same passage in Exodus that Gilson quotes in connection

with Aquinas. Augustine’s conclusions are much the same about that

phrase “I am that I am.” This is one of his key reasons for his

identification between God and truth. He saw the nature of God’s

timeless being as a key also to identifying God with truth. The link

between God and truth is the Platonic “one.” Augustine puts the

forms in the mind of God, so God becomes the forms really. The basis

of this identification is partly God’s eternal nature. From that

point on it’s all an easy identification between eternal verities,

such as truth, eternal being, beauty, the one, and God. The other

half of the equation is God’s revelation of himself as eternal and

necessary through the phrase, for very similar reasons to those

listed already by Gilson, between I am that I am and being itself (or

in Augustine’s case the transcended of being). “He answers,

disclosing himself to creature as Creator, as God to man, as Immortal

to mortal, eternal to a thing of time he answers ‘I am who I am.’”[9]

Problems with TAG

I

am about to present am argument that also uses the term

“transcendental.” Both arguments argue for belief in God. The

difference being that TAG proceeds from presuppositional apologetics,

while my argument is made

on an

evidential

basis.

Both assume that God is at the basis of all knowledge and meaning.

This is what is meant by “transcendental,” it refers to the basis

of the system of thought. My argument uses the TS as an evidential

basis for belief while the presupositional argument merely assumes

the truth of the argument then rejects the presuppositions

of other views. TAG says nothing about signifier.

To understand the insufficiency of TAG (thus they need for a new

argument) we must examine TAG more closely. Greg

Bahnsen was the champion of TAG[10]. Van Til never really makes the argument, never actually states it.[11] TAG is basically just the assumptions of Van Til's presupositional

approach, he wants to scratch starting from a point of neutrality

and

trying

to prove truth and asserting the presuppositions we believe:

“ He

maintained that because God, speaking in his word, is the ultimate

epistemological starting point, there is no way of arguing for the

faith on the basis of something other than the faith itself. God's

authority is ultimate and thus self-attesting.”[12]

That is really the basis of TAG. The problem is he never bothers to

prove it. That is an instant turn off for most atheists, and since he

never states the argument clearly, it's not real clear what it is. I

like the idea of not being stuck with a phony neutrality because most

atheists, at least new atheists lionize their assumptions, at least

in my experience those I've dealt with tend to do that. I don't seek

to argue for total proof but rational warrant for belief. This

argument I will present in terms of the best explanation.

I

think the approach I'm taking will offer a couple of things that Van

Til doesn't. First, In dealing with Derrida’s world of signifiers

and it's concept of the TS we are in a better position to insist that

God is the presupposition, because all the Derridians agree Western

metaphysics accepts TS and that is basically another version of God.

So the difficulty in getting the secular thinker to accept the

premise that God is the presupposition is not as great a gap to cover

if we can start out assuming the tradition affirms a God-like premise

in a logos anyway. Secondly, I don't think Van Til get's us out of

the closed in world of his presuppositions. He asserts that the

Triune deity is the presupposition to all logic, truth, and meaning

but why would an unbeliever assume it? If my argument is successful

it should become apparent that God is the best explanation.

Modern

secular thought can't make the leap outside itself to find God

because it either rejects God or uses itself as the standard of

truth. Of course this is inadequate because that is the problem in

the first place. God is truth but that's not obvious because it's too

transparent, we are too close to the reality. St. Augustine made an

argument that might be considered transcendental in that it assumes

God as the presupposition to truth. Paul Tillich summarizes this

argument:

Augustine,

after he had experienced all the implications of ancient skepticism,

gave a classical answer to the problem of the two absolutes: they

coincide in the nature of truth. Veritas is presupposed in

every philosophical argument; and veritas is God. You cannot

deny truth as such because you could do it only in the name of truth,

thus establishing truth. And if you establish truth you affirm God.

“Where I have found the truth there I have found my God, the truth

itself,” Augustine says. The question of the two Ultimates is

solved in such a way that the religious Ultimate is presupposed in

every philosophical question, including the question of God. God

is the presupposition of the question of God. This is the

ontological solution of the problem of the philosophy of religion.

God can never be reached if he is the object of a question and

not its basis.[13]

One

might ask why, if God is so basic to be synonymous with truth we

can't all recognize it? That is the reason, it's so basic. So it is

with being, we write it off as “just what is” and go on looking

for this “God” who can’t be found because we don’t understand

he’s nearer than our inmost being. Such is the pitfall of

scientific empiricism. The point of course is that God is too basic

to our being, too much a part of the existence we share that we don't

see any indications of presence. We take for granted the aspects of

being that indicate God's reality. Some of the indications might be

physical or cosmological, such as fine tuning or modal necessity.

Others are experiential. The atheists pointed out that water is

physical and can be detected. It's only an analogy and all analogies

break down at some point. Analogies are not proofs anyway. I don't

offer this as proof but as a clarification of a concept. In so

clarifying we find a link to being; the connection between God and

Being itself.

Heidegger

approaches being in this manner, it is ready-to-hand, too basic to

notice. In other words like a carpenter using tools we find being so

inherently part of our experience, so ready-to-hand that we don't

notice it. Paul Tillich worked in the vain of Heidegger, he used the

philosopher to translate classic Christian theology into modern

thought. In that vain we are too close to being, it's too fundamental

to what we are to realize that our place in it is to be contingencies

based upon the reality of God. God is also "detectable" but

of course, not in the sense that physical objects are. Like a fish in

water, being is the medium in which we exist. Given certain

assumptions we can understand the correlation between experience of

presence and the nature of eternal necessary being. When we

experience the reality of God through the presence of holiness we

experience the nature of being as eternal and necessary. All we need

to do is realize the necessary aspect of being to realize the reality

of God. This is why Tillich says:

The name of infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of our being is God. That depth is what the word God means. And if that word has not much meaning for you, translate it, and speak of the depths of your life, of the source of your being, of your ultimate concern, of what you take seriously without any reservation. Perhaps, in order to do so, you must forget everything traditional that you have learned about God, perhaps even that word itself. For if you know that God means depth, you know much about Him. You cannot then call yourself an atheist or unbeliever. For you cannot think or say: Life has no depth! Life itself is shallow. Being itself is surface only. If you could say this in complete seriousness, you would be an atheist; but otherwise you are not."[14]

"Depth

of being" and being itself are synonymous. Depth just means that

there's more to being than appears on the surface. The surface is the

most obvious aspect, that things exist. The existence of any given

thing is the surface level. If we go deeper to probe the nature of

being that entails the realization of the eternal necessary aspect of

being and thus being has depth. Then we realize our own contingent

nature and thus, we are at one and the same time realizing the

reality of God (that is after all the basis of the cosmological

argument and the ontological argument as well. This is why God

seems to be hidden. God is not hiding himself. According to

Hartshorne, "only God can be so universally important that no

subject can ever wholly fail or ever have failed to be aware of him

(in however dim or UN-reflective fashion)."[15] Now the issue of why God doesn't hold a "press conference"

has do do with the fact that God does not communicate by violating

normal causal principles. In process terms, the "communication"

of God must be understood as the prehension of God by human beings. A

"prehension" is the response of an occasion to the entire

past world (both the contiguous past and the remote past.) As God is

in every occasion's past actual world, every occasion must "prehend"

or take account of God.

- It should be noted that "prehension" is a generic mode of perception that does not necessarily entail consciousness or sensory experience. There a two modes of pure perception --"perception in the mode of causal efficacy" and "perception in the mode of presentational immediacy." If God is present to us, then it is in the presensory perceptual mode of causal efficacy as opposed to the sensory and conscious perceptual mode of presentational immediacy.[16] That is why God is "invisible", i.e. invisible to sense perception. The foundation for experience of God lies in the nonsesnory non conscious mode of prehension. So now, there is the further question: Why is there variability in our experience of God?. Or, why are some of us atheists, pantheists, theists, etc.? Every prehension has an initial datum derived from God, yet there are a multiplicity of ways in which this datum is prehended from diverse perspectives.

- I agreed with Hume that sense perception tells us nothing about efficient causation (or final causation for that matter). Hume was actually presupposing causal efficacy in his attempt to deny it (i.e., in his relating sense impressions to awareness).[17] Causation could be described as an element of experience, but as Whitehead explains, this experience is not sensory experience. From Hume's own analysis Whitehead derives at least two forms of non-sensory perception: the perception of our own body and the non-sensory perception of one's past.

- But this is at an unconscious level. However, in some people, this direct prehension of the "Holy" rises to the level of conscious experience. We generally call theses people "mystics". Now, the reason why a few people are conscious of God is not the result of God violating causal principle; some people are just able to conform to God's initial datum in greater degree than other people can. I don't think that God chooses to make himself consciously known to some and not to others. That would make God an elitist. Now, the question as to why I am a theist as opposed to an atheist does have to do with me experiencing some exceptional religious or mystical experience; it does not have to do with amazing experiences that prove. Rather, I believe that these extraordinary experiences of the great religious leaders are genuine and that they do conform to the ultimate nature of things. It's not necessarily a "blind leap" of faith, as my religious beliefs are accepted, in part, on the basis of whether or not they illuminate my experience of reality.

- The experience of no one single witness is the "the final proof," but the fact that there are millions of witnesses who, in differing levels from the generally intuitive to the mystical, experience must be the same thing in terms of general religious belief, the argument is simply that God interacts on a “human heart” (deep psychological) level, and the experiences of those who witness such interaction is strong evidence for that conclusion. This does not, however, remove the usefulness of deductive argument. The argument could be made as an inductive argument based upon religious experiences, yet with greater uncertainty. While deductive veracity is assurance of the truth of a statement, that assumes the premises are true, that's hard to establish with no basis in the empirical. that's hard to do if one finds it hard to believe that deduction can prove God we don't need to argue that. It can establish a rational warrant. For example we can't prove by observation weather the moon was a fragment of Earth or a captured meteorite, until we invent time travel we can't know empirically but we deduce a theory that makes sense. We might never know with certainty but we can have an indication that makes sense. So with deductive argument and God belief. Deductive argument can give us rational warrant for belief. The difference in warrant and proof is the difference in really knowing how the moon came to be and reaching a rational conclusion based upon deductive reasoning. One might ask “where does warrant get us in terms of belief in God?” It doesn't prove but may clear away the clutter so that we can come to terms with God on an existential level.

[1] Jacob

Gabriel Hale, “Derrida. Van Til, And the Metaphysics of

Postmodernism,” Reformed Perspectives Magazine, Volume

6, number 19 (Junje 30 to July 6, 2004) Third Medellin Ministries,

on line Resource URL

[2]

Jaques

Derrida, The End of

the Book and the Beginning of Writing,

New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovonovitch, trans. Gayatri Spivak 1967

in Contemporary Critical Theory, ed. Dan Latimer, 1989, p.166

[3] Ayman

Elhallaq. “Tramscemdemtal; Signiofioed as the basis of

Deconstruction theory,” Literary Theory in Class,

(July 17, 2005) bloh URL:

http://iupengl752-elhallaqayman.blogspot.com/2005/07/transcendental-signified-as-basis-of.html

accessed 5/19/16

[4] Hale,

op cit,

Derrida intentionally spells “difference”

with an “a” to remind the reader that the meaning signifier is

not based upon an essential correspondence between signifier and

signified but is arbitrary and meaning is always referenced by

another word that is itself arbitrary. His overall point is that

there is no ultimate meaning,

[5]

Michael R. Butler.“The

Transcendental

Argument for God's Existence,” online resourse,

URL:http://butler-harris.org/tag/,

viewed 7/3/15.

Mike

Butler is Professor of Philosophy and Dean of Faculty at Christ

College, Lynchburg, Virginia.

[6] Ibid

[7] Donald Keef, Thomism and the Ontological Theology: A Comparison of

Systems. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J. Brill, 1971,140.

[8]

Paul

Tillich, Theology

of Culture,

New

York: Oxford University press,1964

12-13.

[9] Carl Avren Levenson,

John Westphal, editors, Reality: Readings

in Phlosophy.

Indianapolis,

Indiana:Hackett

Pulbishing company, inc. 1994, 54

“…St. Augustine’s view

that God is being itself is based partly upon

Platonism (“God is

that

which truly is” and partly on the Bible—“I am that I am”).

The transcendence of time as a condition of full reality is a

central theme…[in Augustine’s work].”

[10] Greg L. Bhansen.

Pushing the Antithesis, Powder

Springs, Georgia:

American Vision Inc. 2007Ibid.,

6-7

[11] Gordon H. Clark, in Nash, op

cit 301.

original,

Gordon

H. Clark,

"Apologetics," Contemporary

Evangelical Thought (Carl

F. H. Henry, ed.),140.

[12] Butler,

op.cit.

[13]

Paul Tillich, Theology

of Culture,

London, op cit

[14]

Paul Tillich. The Shaking of the Foundations. Eugene

Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2012, 57.

[15] Charles Harthorne, The Divine Relativity: A Social Conception of

God, New

Haven: Yale University press, 1982, 70.

[16] Jon

Mills. “Harthorne's Unconscious Ontology,” oneline,URL:

http://www.processpsychology.com/new-articles/Whitehead.htm

accessed,7/3/15.

[17] This

is common knowledge of Hume's take on causality that we don't see

causes at work. This is the pojnt of the billiard balls.

2 comments:

"Hume was actually presupposing causal efficacy in his attempt to deny it "

While it is common to read Hume as a causal skeptic (or even a causal anti-realist), it is also possible to read Hume as a causal realist. In fact, much of what he says (especially his critiques of superstition) appear to presuppose a causal realist perspective. I think the problem arises from confusing two questions: (1) "What is causation?" and (2) "What is the experiential basis of the idea of causation?"

I also read Hume as a pragmatist (or as having a very strong pragmatist streak) (I also read Kant this way). So for Hume the only proof (or actually 'warrant' - along the same lines as your argument) of causal realism is pragmatic ('custom is the great guide of life', Hume says).

Eric I really wonder what Hume would make of the studies on mystical experience that I talk about I see that as a programmatic argument.I don't say Hume was skpeticalabout causation but e thought we can;t observe it happen in,we have to assume it he didn;t say it wasn;t real. I know there re other ways to read Hume,I value your insight,

Post a Comment