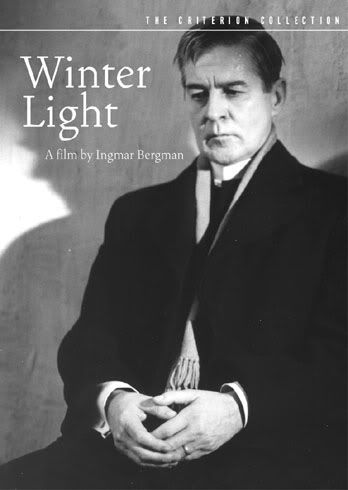

Gunnar Björnstrand

I have reviewed several Bergman films on this blog, starting with my review of his death two years ago ("Greatness has Left the Planet: Ingmar Bergman Dies"). Since getting Netflix last Summer I've been watching what I consider to be the greatest films from the the greatest age of art films. From the late 40s, beginning with Italian Neo-Realism, which followed the lead of Viscanti, to the mid 50s in French "new Cinema" and on to the end of the 60s film make reach it's peak in terms of artistic direction. A host of great filmmakers cranked out sublime creations, the greatest among them was Sweden's Ingmar Bergman. Bergman has a special sensitivity to religion. He was an atheist, he did not pull punches about his feelings of angst at the lack of a God (in his world view) but he was not one of these message board Dawkies. He approaches it with a sensitivity that preserves the dignity and intelligence of the believer.

My favorite example of that sensitivity is from my second favorite film, "Wild Strawberries," and there is a scene I love in that film where two young men are competing for the effectiveness of a young lady. Their contest takes the place of an intellectual debate which grows more angry in every scene. Finally they break into a fist fight and both have black eyes. They are angrily corralled by their companions and put in the back seat with the girl between them. She casually turns to the young seminarian and says "so, does God exist?" Bergman shows sensitivity in a scene where all the travels are together at a table the old doctor quotes poetry about religious belief, the atheist doesn't get it the seminary guy does. So even though he's an atheist he still acknowledges that Belief has its reasons and those reasons appeal to the heart, that doesn't make them stupid. Bergman's father the Chaplin to the Queen of Sweden, but privately he was abusive to the young Ingmar as he grew up. Bergman thus had a sympathy for the religious life but also a revulsion and an acute awareness of the personal struggles that go on in the psyche of believers and seeking unbelievers.

Björnstrand and Thulin in

Winter Light

"Winter Light" is the second in Bergman's Trilogy: "Through the Glass Darkly," "Winter Light," and "The Silence." I have reviewed Thought he Glass Darkly on this bog, and also another Bergman film "The virgin Spring." One of his greats. The review of his death included a review of his greatest work, "The Seventh Seal." That is my favorite film of all time bar none. I am almost having a mystical experince just thinking about that film.

Winter light is like setting out for a wonderful vacation in a great setting such as the south of France, and suddenly finding yourself in a dentist chair for four hours screaming in pain. It has all the slow agonizing tedious built up to nothing of a root canal. Well, one might ask, "what's so great about that, it sounds like a crap movie." The first time you watch it is. But it grows on you. If you think about it latter you come to realize you did see a fine film. I wouldn't not put it in the ranks of the Seventh Seal, or the the Seven Samurai for that matter, but it is a great film. That intense tedium that goes nowhere is intentional. Bergman wants you to feel that. That's the Katharsis. He also wants the film to look dismal, soul crunching, cold, barren, stark, bleak and it does. The setting is a small Island off the coast of Sweden. It has modern convinces but everything is shabby and gritty and the people are isolated and the region is a backwater.It's the kind of place that one begins a practice in (say in medicine) because there's no where to go from there but up.

The first scene is in a church as the Sunday service begins. In fact, the whole film takes place on that Sunday between the noon service and the evening service which is only bout three and half hours. The building is interesting, the service is dismal. The building is old and crumbling with vaulted sealing and very Norse looking statues of Christ on the cross. There are only seven people in the whole church and they are spread out around the sanctuary. The only people who sit together are one couple, the others all lonely individuals who have no one to sit with even in spite of their being a small enough group to have an intimate service. The service is anything but intimate. It's mechanical, and legalistic, formal and by the book. The people in the service, with the exceptions of an old woman and a a hunchback who seem moved by it all.

The opening of the film and the slow unfolding of conflict imply a real slap in the face to Christian belief. The minister, by played by Bergman's best friend Gunnar Björnstrand, mutters under his breath "what a ridiculous image" as he gases at the cross.Everything is old and falling apart, ony two out of seven parishioners who bother to show up really get anything out of it, the rest is all perfunctory because it's expected. The minister (Thomas) stays to talk to the one couple who sat together. The man is a fisherman played by Max Von Sydow (the Father in Virgin Spring, also the exorcist himself in that fim). The fisherman's problem is that he's depressed, to the point of suicide, because he's fretting about the bomb. This is a very periodized anxiety of that era. In that day it would have spoken to the audience. But the minister is totally inept at dealing with the man's problems. He gets him to agree to come back latter and talk to him in private session without his wife. The couple leaves and the minister's girl friend (Marta--Ingrid Thulin) comes in. She is clinging and mothering and hovering and suffocating. She gets him to read a letter which he reads before the return of the fisherman. The content of the letter is a sketch of all the problems in their relationship. The intensity builds as the text of the letter is acted by Thulin. The scene is a masterpiece as Bergman does not allow the camera to stray from a close up of her face as she speaks the text which the minister is reading. This is violation of all the rules of film making. The close up grows in intensity as the problems of the couple are revealed. The viewer wants to move on but can't. The intensity of the letter is drilled into the face of the audience.

Thomas is sick, he has fever but he's pushing himself. In real life Bergman got the doctor to prescribe ineffective medicine for Björnstrand's bronchitis so he would really appear sick. While we might give Thomas some points for sticking to his duty we have to subtract Thomas again because his councilmen technique was total inept. He did not talk about the man's problems at all. Instead he told the fisherman about his own problems. He confessed his lack of belief and all but said things are pretty hopeless. He talked about is ideas of God but not in a way that shed theological light but in an intensely private way that could only be described as self indulgent.The man leaves clearly more distraught than when he came. Surprise, he goes right out and shoots himself.

There is a great scene, the only real outdoor scene where Thomas goes to issue last rights and help with the body. The Fisherman has shot himself in front of a stream which is moving very swiftly. There are mountains around, but none of it is beautiful. Of cousre it's black and white but even so nature can be beautiful in black and white, the great open outdoor forested scenes of Virgin Spring are wonderfully Beautiful, this is not. The stream looks cold and bleak and like one might drawn. The mountains look gritty, everything looks gritty, snowy stark and bleak. This is of course, the way Bergman wants it to look. The American Title is "Winter Light" so named because the quality of light in the film is muted. this is the light of the winter in Sweden, dark, somber not happy sunshine but cloudy and stark. The scene focuses on a body being put in a body bag. Thomas doesn't seem shaken as much as bored. He's so self absorbed even this guy's doesn't make him re think what he's doing.It's clear he has no calling. He's just a guy doing a job. He could be a plumber. One can't help but wonder if this wasn't Bergman's feeling about his father's ministry.

The arch of conflict come after this scene where Thomas and Marta have a showdown int he school where Marta teaches and lives in the back. Thomas basically lets her have it. He doesn't like her. he tells her so. He is humiliated her, she's clinging and so forth. She has a habit of calling "poor little Thomas" and hanging to his back. But it's clear if we read between the lines that her main sin is she is not his dead wife. He was really in love with his wife, he says, he will never get over her. He speaks of her "mockery of my dead wife." Marta looks helpless and breaks off her sobbing to say "I didn't know her." To me that means he does see a similarity between the two, but resents it. Marta does have some qualities that his wife had, but she's not the right woman.

Before the evening service Marta sits in the pew and talks to one of the seven, now six members of the church, a little hunchback guy who plays the organ. The hunchback, payed by Johan Allan Edwall, tells her that Thomas and his wife had the same problems that she and Thomas have. Thomas has exaggerated his love for her becasue she's gone and though guilt built her into a saint while she was actually clinging and smothering. He also observes that Thomas talk of searching, is there a God and so forth is just a way of keeping at bay the realizations about his own character flaws. His search for certainty is a false search because he's using God as a scape goat and search for certainty of himself not God. The real Swedish title of the film is a word meaning "the communicants." That has a double meaning because it applies to the parishioners of the church doing communion but also to the communication between the characters: in both cases it's an ironic title because their doing of communion is hollow and without feeling and their communication is non existent. The only real communicating done in the film is he little hunchback's analysis of Thomas and his revelation to Marta that Thomas and his wife also had the same kind of relationship. The Hunchback is also the only real religious character in the movie. He's the only one (other than perhaps the old woman who is only in it for one fleeting close up at the beginning) for whom faith is really a way of life and really moving.

The film ends with the beginning of the evening service. There are only three people there for the service, the hunchback, the minister and the former girlfriend. But Thomas goes on anyway. He begins "Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God almighty..." as though those meaning anything to him. Another formalistic service by wrote, never mind that the audience is only one person (the other guy plays the music). As long as one person is there the service must go on. We can take this in two ways, either "the show must go on" a dig at Christianity becasue they are so pathetic that even with just three people they still can't depart from the script. Or we can see it as hope because even if only one person receives it the word of God is not lost.

The devastating critique of Christianity and its' position in Swedish culture in this film are obvious. What can be seen if one looks closer are the points of Bergman's sensitivity to religious belief. The only really "together" character was the only religious character who sums it all up in a knowing way and does only actual communicating in the film. The hopeful aspect of the end, even though a bleak winter kind of hope, that even if only one person hears God is still there, the word is not spoken in vein. Of course Bergman didn't believe God was there, but what he actually did believe is unclear, what is clear is that he actually did have a sense of admiration and sympathy for the true believer and the true seeker.

This film reminds me of the life of great theologian Carl Barth. Barth came out of seminary typical nineteenth century liberal. The triumphalism of post millennial was shattered by WWI and he had nothing to say to an audience. He was put in charge of a parish where only three old women came tot he service. But he didn't go by wrote, he formed an intimate little service and discussed what to do about it. He learned from these women what they needed to hear why they believed, why the modern church had nothing to day to people. From there he launched his revolution in neo-Orthodoxy whic brought people back to the churches.

Winter light is a great film, even though I wont put it on a level with Bergman's greatest, ironic since he wanted it to be part of the great Trilogy, like all great films it leads one to think about great ideas.

8 comments:

You said, "So even though he's an atheist he still acknowledges that Belief has its reasons and those reasons appeal to the heart, that doesn't make them stupid."

Bravo for him, and you for sharing.

Your commentary is very well written, actually the only good one we have managed to find of Winter Light and it is obvious you really get into the film and its meaning. It is very refreshing to read thoughtful critiques instead of mere sypnosis of the plot or anti-religious raging vagaries.

You would like to give you an excuse to watch the film again to clear out a couple of minor confused memories of the last scenes. There are actually four characters in the chapel in Frostmass (frost instead of Crist +mass= not a mass of\for\from Christ, but of frost, that is if frost is frost in Swedish.... The hunchback is the sexton, not the organ player. The hunchback seems to be a religious person, and the only one who is actually reading the Bible (though he started for all the wrong reasons, and used it as a sedative to go to sleep. He has got interested by the passages about the passion, and comments on the emphasis on the physical suffering of Christ (which is actually not so much so in the biblical accounts). He points that Christ's spiritual suffering must have been much greater: loneliness, indifference to him from friends, being deserted,feeling abandoned by God the Father himself). He implies that Christ Himself must have doubted (mmmm, partial interpretation?,we are forgetting about Psalm 22 and fulfilment of prophecies, the role of Christ as substitute, and the horror of suffering for human sins...) Anyway, that is seen to strike home with the minister, who then goes into the chapel and does his performance again, with Martha(the diligent, obsequious servant), the deformed sexton (neurotically exacting in his ritualism, but having gained an ever so small speck of insight), and the cynical bufonesc organ player.

I agree on the multiple possible readings: the show goes on, it is a show alright. But then it is the unbelieving that makes it a show, a vain ritual, not faith. The irony is that the unbelivers cling to the ritual unable to free thamselves. The chapel is empty of believers, except maybe, the sexton, but then why shoul true believers attend this mockery of spiritual communion? Martha's prayer before the service begins is, well considered, the truest prayer: an honest humble recognition of failure, helplessness, self-abhorence. The closest thing in the film to the possessed boy's father who said to Jesus "I belive, Lord, help my unbelieve" (Mark, 9:24), though not quite there. It may also hint that to these wretched people, even this pitiful scrap of the Gospel is better than no Gospel at all.

I was an atheist until 32, brought up by an atheist Father who has come close to taking orders and a Roman Catholic mother whom I never saw read the Bible, do other than recited prayers once a year to bless Christmas dinner and who did not, at that time,any meaningful spiritual relationship with God either in theory or in practice.

Like Martha in the film, there came a point when the revelation to my conscience of human crookedness, more so of my own, brought me down to my knees. I too, like Thomas, a doubting Thomas, was angry against a God I swore I didn't believe in.

Like the deformed sexton, I too am pathetic in my every effort to do good. Like the cynical organ player, I too feel the compulsion to give myself over to sin and the apparent sense of liberation of not following Christ. But having been there, I know what to expect of myself and the world, and having tasted just a little bit of the Jesus who said "Love your enemy", "come to me, you the overwhelmed and fed-up", "Father forgive them", "Love one another as I loved you",and "Those that listen to me are my mother and brothers and sisters", I'd rather stay out of the palace and the city and in the tents with God.

Keep up the excellent writing and pithy comments.

With respect and affection in Jesus,

Cristina Newton

thanks for your kind words. I am so glad my film reviews meaning something to someone. Yes I really love great film and Bergman is my favorite.

Bergman was an atheist. he wasn't making a Christian allegory. He was not the kind of hateful little mocking ridicule artist we find on message boards. He admired religious people and tried to stay as close to religion as possible without actually being religious. If he hinted at some kind of believing subtext, and I'm not saying he did, we can expect it to be very liberal. If he had a view of God it was probably an existentialist view.

“Winter Light” by Ingmar Bergman (1962) is the second part of his “religious trilogy” (the first, “Through Glass Darkly” – 1960, and the third, “Silence” – 1962). In the first film, the basic (for achieving enlightened life) human abilities – to love without psychological defensiveness and to be vital without de-sublimation, that together as a sacred combination make human beings spiritual creatures, leave the existential circumstances of human life and retreat to “heavens”. In the third film of the trilogy “god” (the form in which the unity of human love and human vitality take place outside life) has “died” and human beings have to start from the beginning. But “Winter Light” depicts the situation when “god is silent”, and human beings slowly grow towards understanding that it is up to them to return their libidinous vitality back into the (earthly) life. In all of the films of trilogy Bergman’s points about spiritual life are mediated by the scrupulous psychological analysis of the characters.

“Winter light” is a metaphor of light of love/vitality in a condition of being distant from human life. The film depicts the Christian faith of seven characters – Pastor Tomas Ericsson and the six parishioners of his Church (three men and three women). Each protagonist‘s faith is uniquely created by their individual intelligence and will in the unique circumstances of each of their lives. Bergman approaches each character’s religious belief as sacred reality, as a precious creation. Some of the personages he personally admires, some he respects and others are objects of his “loyal criticism” that is full of empathy and good faith.

The frankness and gracious intensity with which the director depicts the human destinies and encounters between the characters are overwhelming, as much as actors’ performances make each individual soul radiate its own truth. Each personage is represented as having been formed by life and human history, nothing is fabricated in order to entertain or sentimentally please the audience. With all seriousness, the film is so congruent with human emotions that it is taken inside human soul as naturally as air for our lungs.

The film addresses Christians of various denominations, as much as people of other beliefs and non-believers with equal authority, and is an icon of not only a philosophical, but a humanistic cinema.

The film confirms that Bergman’s cinema is made for 21st century even more than it was for 20th century.

By Victor Enyutin

how does that really differ from what I said?

Post a Comment