Bergman

Through a Glass Darkly is is the first of Bergman's Trilogy, the other two parts being Winter Light, and The Silence. Even Bergman put a great deal of time and effort into these three films and considered them seminal for his film effort, none of them turned out to be his greatest films. like Filini's Eight and A half, Through a Glass Darkly is boning, hard to watch and tedious, but at the end in the final scene it all comes together in a cumulative effect; you suddenly realized you have struggled through to find that it is a great film after all and you feel proud of yourself for making the effort. The title refers to St. Paul's statement in 1 Corinthians "though we see through a glass darkly, when that which is perfect is come I will know even as I am known, face to face." The reference is to a mirror in the ancient world. They did not have good mirrors and one could not get a good image of one's own face. The idea of Bergman's film is subtle psychological implication about knowing first ourselves, then others, finally reality itself and even God. God is all over the film but in a subtle way. Bergman was an atheist, but since his father was a minister and spiritual adviser to the Queen of Sweden he could never let go of the question of God. Bergman rebelled against his father's faith as a young man, as a middle film maker he showed a lot more sympathy for the question of belief than a lot of atheists I find on the internet.

Bergman first made a name for himself as a young directing coming of theater in the late 40s. His films were not popular and he was known as one of the "angry young men," the group of artists in Europe who challenged convention and took up early counter culture themes. Through a Glass Darkly is a change for Bergman. He went with a new look as he was not able to work with his usual cinematographer, Gunnar Fischer. It was Fischer who gave Bergman's films their look, the look for which art films of that era are constantly mocked and parodied; one candle power wroth of light and brooding figures in black playing chess. On this project Bergman was forced to go with Sven Nykvist. Nykvist prefered natural light. The movie is much brighter than previous Bergman movies, lots of out door scenes and nice windows. This is sense light flooding the inner chambers reinforces the themes of psychological searching.

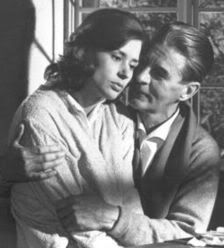

Harriet Andersson (Karin),

Gunnar Björnstrand (David--the father)

Bergmanorama:

The film describes 24 hours in the life of a family on an isolated island in the Baltic where they spend their summer holidays. The family consists of four people: the father, an author (Gunnar Björnstrand), his adolescent son (Lars Passgård), his daughter (Harriet Andersson), and her husband (Max von Sydow). The daughter is the central figure—she is a latent schizophrenic, and her father, her husband, and her brother are involved in and share her fate each in his own way.

At the center of the family is the father (David). He is a loved and revered figure but hardly has time for his family. He's always absent. The inadequacy of his Fatherly devotion is illustrated in his pathetic attempt to give gifts early in the film. They are dining outside and the subject of his absence comes up. To take their minds off it he distributes his gifts which he bought for them on the last trip. But as he goes inside for something, his camera, we find that the gifts are woefully inadequate, one has the thing given, one is given something the was given last time, one is given something trivial. But as we move inside to what the father is doing we find he is weeping profusely. He then spreads his arms wide apart, his silhouette lit by the window and his body forming a cross. From this we have a subtle religious image and our first hint that something is up psychologically with the character.

After dinner the sun Minus (pronounced Meen-noes) and the sister Karin put on a little play that Minus wrote. It centers on a conflict between perfect decimation to one's art vs the need to live life. A prince is confronted by a ghost of a queen who offers him eternal life if he will agree to die and be entombed with her that night. He at fist affirms the greatness of the choice, since romantic love is his art from and his art is much more important than life. Then he parades through string of excuses and finally backs out. This represents the conflict in all of Bergman's films between true artistic devotion and the need to compromise with life.

The father wishes to be a great writer. He is a doctor but he writes novels. Early in the morning the daughter rises and goes secretly to an old abandoned room. The walls and gritty the book floor ever old and musty, there is nothing in the room but a chair and the floor is uneven and warped. The girl presses tightly against the wall and talks to someone who is not there. Then she goes to her father's room and reads is diary. We find out latter that a voice told her to do this. Her father has written about her conditions, which is hopeless. We are not really told what her problem is but it's some form of degenerative disease that results in insanity and death. She knew she was sick and had been in a mental institution before. In her father's diary, however, she sees that he conditions is hopeless. What really disturbs her is that her father written some absurd statement about recording her reactions to the disease and how me might contribute to medical science if he studied her demise. She of course reacts with horror as though he is only concerned with her an organism to study.

We find out in a latter conversation that the father is extremely repentant about ever having written this. The son in law (Martin) confronts him and tells he he has always arrogant and cold toward his children. David tells Martin, and us< that he knows this but recently has undergone change which he can't expalin and now only seeks to be there for his family. Meanwhile throughout the movie the son Minus voices the usual adolescent sense of failure and hopelessness at feeling so unattractive to the opposite sex, his sister seems to have an incestuous fixation and is always hanging on him and kissing him (which he hates of course). All of this underscores the theme voiced by Minus that we seek to know the ultimate truth, we seek the basic meaning of life and the sense of validation all the time. That validation he wants to find in the relationship with his father. He expresses the thought "if only I could really talk to father, I wish Papa would talk to me."

In the end Karin tells Martin that she goes "behind the wall" in the abandoned room where strange people are waiting there for God. This makes her feel calm and happy and she will be allowed to wait in that room for God to come. She goes into the abandoned room and seems in rapture waiting for God. She has already exhibited ear marks of break down so they have summoned the care flight. We see the example of Sweden's wonderful universal medical care system, their socialized medicine, the best int he world. The care flight comes the vibrations of the helicopter cause the closet door to open by itself (it was not latched). Karin totally freaks out. He just goes hysterical. We find out soon enough that in her delusional state she saw the "god" who turned out to be a giant spider who tried to climb inside her.

In the final scene at the end of the day, Karin and Martin are gone and the father and son are there alone. They begin to talk and the father tells him his theory of God. He has come to see by means of a revelatory experince that God is love; this includes all forms of love. Any kind of love that is pure love is God. As they discuss this concept the father says good night and goes to his women the son looks astonished and says "Papa talked to me!" Of course we should probably understand that more than just the earthly father is hinted at here.

Through A Glass Darkly is not as fun to watch as Bergman's great films, The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries (my two favorite movies) or the Virgin Spring But I do recommend it. I think it's important because is illustrates how the question of God's existence can be carried on by an atheist and how one can bring a kind of answer to solution that is not anti-religious while not embracing a religious tradition or even a theology. While fundamentalists might scough at his as counterfeit of truth, and certainly I would not present it as my credo at seminary I see it as hopeful becasue it demonstrates that even in a secular society and among atheist types people still think about God and find answers that at least set them in the right direction.

No comments:

Post a Comment