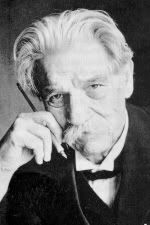

Albert Schweitzer

This is probably the best article I ever wrote. It was published under the name J.L. Hinman (my name) and published in Negations, Winter of 1998. That was the academic journal that I published. It was peer reviewed. I know it's long, but hey this is my real work here. This is my academic career. In a couple of days we will get back to God stuff. Although I believe this is theological.

... The ethical ideas on which civilization rests have been wandering about the world, poverty stricken and homeless. No theory of the universe has been advanced which can give them a solid foundation...--Albert Schweitzer

Before there was Mother Teresa, there was Albert Schweitzer. At the time of his death in 1965, he was the household symbol of the best sacrificial instincts in humanity, a man who gave all he had to serve among the poorest of the poor. Unlike Mother Teresa, however, Schweitzer gave up not one, but four brilliant careers to became a doctor in equatorial Africa. Today he is chiefly known for his medical mission, and secondly as the theologian who shaped our modern view of early Christian eschatology.1 Yet, in addition to being a theologian, minister, and concert organist, Schweitzer was also a philosopher. Yet today, his philosophy has been forgotten. When he went to Africa, it became easy to tuck him away as a convenient symbol of humanitarian sacrifice, and to ignore the bothersome notions which had shocked thinkers of his day: Schweitzer argued (as early as 1900), that civilization was already dead, and that we live in a barbarous society. In so arguing, he anticipated much of Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man, and C. Wright Mill's notion of the "cheerful robot," as well as the decline which now besets our society. In 1923 he published, The Philosophy of Civilization2 While many of Schweitzer's ideas are quaint, seemingly outmoded, even naive, they contain a profound nature. In an age when "civilization" is either vilified as hierarchical, exploitive and environmentally unsound, or it is reduced to a sociological examination of cities, it may help to know that, at least according to Schweitzer, we are beating the wrong dead horse. Schweitzer argues that the concept of civilization has been forgotten, and the material infrastructure which accompanied it historically has been put over as the thing itself.

Schweitzer was born on January 14th, 1875 at Kayserberg in Upper Alsace, his father was a minister from a long line of ministers, and he was the older cousin of Jean-Paul Sartre. He grew up in Gunsbach in the Muster valley. In October of 1893 the young Albert became a student at Strasbourg University. He attended the lectures of Heinrich Julius Holtzman (New Testament), Wilhelm Windelband, and Theobald Ziegler (history of Philosophy), all of whom became his academic advisers and close personal friends.3 In July 1899 he took his doctorate, and shortly after that he began a position on the theological faculty at Strousbourg, and another position as an assistant minister at a small church near by. He began work on his best known book, Quest of the Historical Jesus4 in 1901, it was published in 1906. By that time, he had already declared his intention to become a jungle doctor (which he announced to family and friends in October of the previous year). The decision was a bombshell for all who knew him, (Ziegler burst into tears) and everyone tried to discourage the idea. Schweitzer himself said that the decision was based on a natural realization one morning as he woke up, he had been allowed a happiness and success that the vast majority of people never know, and now it was time to do something concrete for the happiness of others.5 He began work as a medical student in 1905, while continuing to do some of his greatest theological scholarship, including a revision of the Quest. Some where along the way he also found time to write a book on Bach, and a book on Organ building. He continued his intellectual work and music throughout his life, writing The Philosophy of Civilization while a jungle doctor in Africa (completing the work in 1923).

The Philosophy is divided into two parts, The Decay and Restoration of Civilization (also published as a single volume by Unwin books) and Civilization and Ethics. In part I, Schweitzer argues that we live in a barbarous society because the concept of civilization has been forgotten. The notion has become confused with the trappings of the material infrastructure of civilization; the "modern" industrialized world of technological production. But, civilization is not merely in-door plumbing, telephones, and sky scrappers, it is a notion built on ethical assumptions. In part II, Civilization and Ethics, Schweitzer deals with a long and detailed analysis of the failure of ethical thinking which led to the decline of civilization. Schweitzer defines Civilization as "the sum-total of progress made by `mankind' in every sphere of action and from every point of view, in so far as this progress is serviceable for the spiritual perfecting of the individual. It's essential element...is the ethical perfecting of the individual and the community" (translation notes, 69). This definition, is fraught with the baggage of a terminology long outdated, and laced with the metaphysical assumptions of an age which we are coming no longer to understand. Nevertheless, it encodes the philosophical givens of Schweitzer's day ("progress," "individual," "spiritual"); they are anathema in our time. Rather than try and unpack these definitions at this point, because that would require unraveling an entire world view, it would be better to use them operationally at the moment, and to explain Schweitzer's use of them in the context of his notion of civilization.

For Schweitzer, civilization consists in the efforts of individuals, as part of the mass, to overcome the struggle for existence and to establish favorable conditions for living. But, "favorable conditions for living" involve more than food and housing, but also the situations in which the artistic and intellectual ("spiritual") freedom of the individual can flourish as well.6 The struggle is twofold: to overcome the limitations imposed by nature which make living burdensome (physical survival), and that of conflicts between people. This latter suggests the necessity of ethical content, it also implies something more than mere survival, since humans seem to be constituted such that mere survival is not enough. We also create culture, and when culture reaches a level such that the intellectual and artistic is able to flourish, and the ethical level obtains a degree of moral excellence, we are civilized (Decay, 41). Schweitzer's notion of "progress" was not Hegelian, not based on some inevitable telos, but based upon a more practice desire to solve problems. In the late 19th century, however, according to Schweitzer, the grand metaphysical systems of the day collapsed, and in so doing, took the ethical assumptions they had co-opted with them. Having stripped the "spiritual" dimension from the equation, all that remained was a physical definition of civilization; civilization came to be seen as overcoming nature and establishing highly organized and viable living conditions in a purely physical sense. In other words, the totality of the twofold struggle is reduced to its material components alone, and the concept of civilization is limited purely to its material dimension.

Schweitzer saw the results of the loss of civilization taking shape in concrete interactions between society and the material conditions imposed by economic forces. "[hindrances to civilization] are to be found in the field of spiritual as well as economic activity, and depend above all on the interaction between the two" (9). Civilization is the result of people thinking out the ideals of progress and fitting them to the concrete situation of their lives (Ibid.). Civilization, therefore, depends upon freedom of thought and action. "Material and spiritual freedom are closely bound up with one another. Civilization presupposes free men [and presumably women] for only by free...[individuals] can it be thought out and brought into realization. But today both freedom and the capacity for thought have been diminished" (10). Just as C. Wright Mills and Herbert Marcuse7 would argue four and five decades latter, Schweitzer saw an inverse correlation between freedom and capacity for thought on the one hand, and the rise of material abundance and prosperity on the other (Ibid.). The struggle for abundance, the imposition of material conditions for survival in an industrialized society, and ideas of self-interest which result from this way of life, subsume the ideals of civilization, and the energy and time it takes to ponder them.

In much of his analysis Schweitzer sketches out a sense of modern life which anticipates Marcuse's One-Dimensional Man. In the opening lines of that work, Marcuse speaks of "a smooth, easy, reasonable democratic unfreedom...,"8 so Schweitzer observers, "...through revolutions in the conditions of life...[humans] become in ever greater numbers, unfree instead of free" (87). He sketches an historical development of capitalism with almost Marxian overtones.

The type of man who once cultivated his own bit of land becomes a worker who tends a machine in a factory; manual workers and independent tradespeople become employees. They lose the elementary freedom of the man who lives in his own house and finds himself in immediate connection with Mother Earth. Further, they no longer have the extensive and unbroken consciousness of responsibility of those who live by their own independent labor. The conditions of their existence are therefore unnatural. They no longer carry on the struggle for existence in comparatively normal relations in which each one can by his own ability make good his position whether against Nature or against the competition of his fellows, but they see themselves compelled to combine together and create a force which can exert better living conditions (87-88).

Perhaps Schweitzer lacked Marx's faith in the nature of class struggle, but he understood that the industrial age, in so far as it had crated a streamlined version of class antagonisms, and moved workers from their own sphere of life and work, into the factory or the office as cogs in the machine. As Marx stated, "The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society... all that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned."9

Moreover, the pace and tension of this way of life, a life that counterfeits civilization in the techniques which have built the material apparatus of a once civilized society, place such demands upon our mental energy and time that the ideal of civilization, and the practices of freedom are forgotten. In time we come to accept the material abundance and the rigors of maintaining the infrastructure as a replacement for the thing itself. "Overwork, physical or mental or both is our lot. We can no longer find time to collect and order our thoughts. Our spiritual dependence increases at the same rate as our material dependence" (88). He speaks of the growing power of the state, of the increase in political organization, and economic forces which strangle the individual and necessitate conformity (Ibid.). While Marx sees class struggle as an inevitable result of capitalistic ownership, Schweitzer sees it as a threat to peace, a problem necessitated by growing industrialization and the greed of ownership. Where Marx saw class struggle as a logical social outcome, Schweitzer saw it as a necessary although problematic and dangerous reaction to a situation which had no other solution, yet he places the blame squarely on the shoulders of the capitalists: "...it was machinery and world commerce which brought about the war (WWI) "(Ibid.). But in the final analysis, he is arguing that all of these ills, class oppression, war, and economic deprivation, are the result of losing the concept of civilization, and of mistaking the historically bound material conditions which accompanied it for the thing itself.

Schweitzer argues that in so far as workers are separated from the total production process, the individual becomes a mere "cog in the Machine." This holds true for office work as well as factory work. The office worker shuffling papers (or pounding the key board) is also left out of the over all production process, so that there is no sense of craftsmanship, no sense of the overall purpose. A mentality is cultivated in which the "bottom line" is all that matters. The reason for producing the product in the first place is lost. Profit margins become the reason for all our endeavors. As people become their jobs, plan careers around orbitrating production problems and maintaining cost effectiveness, etc. the notion grows gradually that the commodified product is the standard model against which all of life may be judged. "Excellence" in life becomes greater efficiency in production.

The resulting affects upon popular culture transform leisure time and entertainment into even greater anti-civilizing forces. Predicting the sound-bite and the "dumbing down" that we now see all around us, he comments on the simplification of newspapers compared with those of the nineteenth century, the result of time constraints on readers (12). He speaks of how the worker must spend leisure hours in vein entertainment since his/her energies have been drained to the point that any serious contemplation is futile "To spend the time left to him for leisure in self-cultivation, or in serious...[conversation] or with books, requires a mental collectedness and self-control which he finds difficult" (11). Schweitzer's words reflect an interest in books as a part of mass culture which is unknown today. Of course, they didn't have as many ways to waste their time in 1923, and so they tended to read more. But, the nature of an ever expanding entertainment and leisure market have meant a totally different way of life, one in which it is natural to expend energies on fruitless and pointless entertainments, and attempts at serious conversation are often a serious social transgression.

As civilization is lost conceptually, it is replaced conceptually by a shift to the organizational structure of its own physical infrastructure. Organizational structure comes to be seen as civilization itself, and organizational strategies come to replace ideals. Learning and thinking become specialized and segmented(16). On this point he anticipates C. Wright Mills argument that the rise of organizational bureaucracy limits freedom. As the arms of bureaucracy stretch forth, as workers lose the global vision of their activities, the goals and ends of their lives, they come to rationalize their lot in the overall scheme of things. The opportunity to reason about life is replaced with rationalization, no one can follow the big picture. The system takes on a life of its own, even the leaders, "like Tolstoy's generals, only pretend to know what's going on." (Mills, op. cit.). Specialization of knowledge and scientific reductionism are the result of the decay of our concepts of civilization. "Most clearly perhaps in the pursuit of science, we can recognize the spiritual danger with which specialization threatens not only individuals, but the spiritual life of the community...education is carried on now by teachers who have not a wide enough outlook to make their scholars understand the interconnection of the individual sciences, and to give them a mental horizon as wide as it should be" (13).

In the latter part of the 20th century, these trends in education and reductionist thinking have reached critical mass, they have created a situation in which the loss of a concept of civilization creates further erosion of civilizing forces. A hefty portion of the work of professors now consists in trying to fill in gaps left by the educational system. Still more alarming, however, is the realization that the educational system itself is being dismantled and replaced with a corporate training system. A study by the National Alumni Forum found that two thirds of the colleges and Universities answering the survey do not require English majors to learn the Western literary canon. The emphasis has been shifted from Homer and Dante to boxing stories, gangster films, and soap operas. Only 23 of 67 schools responding required Shakespeare.10 It is not that society will fall apart because people don't read Shakespeare, but, the perpetuation of civilization as a concept requires at least passing familiarity with the greatness of the past. When Graduate students can spout off reams of regurgitation about Derrida or Lyotard, but have never heard of Dante, there might just be an indication that something is wrong. As it will be argued further down, civilization is passed on through the tradition of letters. Knowing the tradition as a continuous chain of literary and philosophical links is part of the process of maintaining it (and losing the links, Schweitzer argues, is part of the problem). While many of the respondents site student choice as the main reason for dropping requirements of canonical writers, others refer to the trendy ideologies of the day (Ibid.). The canon is hierarchical, we must not privilege one writer over another. Of course the effect is that boxing stories are privileged over Faulkner or Joyce.

More and more, universities are becoming the servants of corporate finance. Originally, state universities were conceived as a way for working class kids to get a college education. As the consequences of Reagan's tax revolt continue to work their magic, however, fewer tax payers are willing to foot the bill. Education is no longer viewed as a means of passing on a repository of knowledge in culture, but merely a means of job training. State Universities are more often forced to seek private funding, which ties them to corporate needs and expectations. The results of this trend are devastating for academic freedom. "Knowledge that was free, open and for the benefit of society is now proprietary, confidential and for the benefit of business. Educators who once jealously guarded their autonomy now negotiate curriculum planning with corporate sponsors... [emphasis mine] ...Professors who once taught are now on company payrolls churning out marketable research in the campus lab, while universities pay the cut-rate fee for replacement teaching assistants... University presidents, once the intellectual leaders of their institutions, are now accomplished bagmen."11

Moreover, the avenues of learning which once offered the working class a means of entry into the rarefied world of letters, are being dismantled. As a case in point, the State University of New York, (SUNY) once offered affordable education to the poor, and many students who began in the humblest of circumstances wound up getting Ph. D's. But, SUNY is being taken apart, it's funding curtailed, and it's future tied to corporate leadership. Mayor Rudy Giuliani has called for an end to open admissions at CUNY, (City University of New York) which is also being overhauled. "In recent months, SUNY and CUNY have come under a barrage of attacks from anti-tax activists and right-wing think tanks and from the Republican politicians whose budget-cutting frenzies they feed..."12 Solomon documents the involvement of the Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation, the John M. Olin Foundation (a mega funder of right-wing think tanks) Scaife Family Foundations, the Manhattan Institute, and many others. The major reason for "reform" cited by the Mayor, is that the system is a failure--remedial courses, only 9% of the students graduate in four years (which is true of most baccalaureate graduates now days, as the Center for Educational Statistics shows (Ibid. 6) and only 1% from the cities community colleges in two years. The content of courses is also sited, the emphasis upon popular culture rather than the classics, but the "reformers" are not replacing these remedial courses with Dante and Milton. They infuse corporate need into University life, and orient the program along the lines of a job training program. "They speak of the degrees they grant as `products' and their students as `customers' and insist upon `productivity measures' that are more appropriate to widget manufacturing than to broadening students' knowledge and critical faculties."13

While academics try to justify abandonment of the Western tradition of letters with the most ideologically trendy line, the economic realities lurking behind the problem speak for themselves. The American publishing industry is going under, with sales of adult hardcover trade books slipping 7% in one year (1996-1997). The sale of Randomhouse to the German company Bertelsmann is a prime example. It is not that publishers are selling so few books that they can't stay in business, rather, the expectations of booksellers are not being met. Publishing has changed profoundly over the past 30 years. "Today's books are more like grocery products than works of literature. Publishers scrutinize an author's sales history and before buying a new title they consult with the marketing and sales departments about the books chances."14 As the concept of civilization collapses, art and literature are reduced to commodities. A rash of corporate takeovers in the `80s and early `90s transformed the publishing industry. "Under corporate ownership, the cultural appeal of books began to give way increasingly to bottom line considerations. Media czars, expecting books to yield the same 15%-20% profits as their other current businesses..." (Ibid.). Thus, publishers try to compete with other forms of media by holding publishing hostage to market research. While there is a valid question of causality involved here--is the failure to teach and respect the canon the cause or the result of this cultural drift away from serious reading?--it is not hard to see that Universities and other institutions of "higher learning" are doing precious little to prevent the consequences. Not only are the very people who should be furthering the tradition, seeking the theoretical means to justify its demise, but the University itself is imperiled.

One might add to the litany the state of the arts. While the explosion in small presses has brought with it an abundance of very prosaic poetry and a flourishing small press movement, the situation for artistic institutions is very different. "Every major cultural institution, from the metropolitan Museum of Art to the New York Public Library to Lincoln Center would collapse immediately if it were at the mercy of market forces...now a handful of entertainment conglomerates have become the main suppliers of cultural products, and even popular arts, it is argued, have suffered under their watch."15 "High culture," is an acquired taste. Society is no longer very interested in passing on that taste, thus, the market cannot support it. As we grow more dependent upon market forces, the emptiness of the culture begins to feed upon itself. The educational system must work twice as hard, it must battle both the tax revolt, and the culture itself; a culture which has been taught to despise learning and thinking. Without the concept of civilization, all aspects of life are reduced to commodities, and the commodification becomes the only valid pursuit, dominating all taste, all vision, and all aspirations.

The common link in each of these problems is between the loss of civilizing influences and their affects upon society. Each new problem which emerges becomes in turn a new source of the loss of civilization. Popular culture is a good example. As the culture itself takes on a reduced aspect in its "spiritual" milieu, (capacity for free thought and artistic expression), the resulting popular culture creates mazeways through which the next generation grows up even more separated from the ideals and pursuit of civilized life. The next generation grows up thinking of civilization as freeways and flush toilets, with no concept that it could be an ideal of behavior or of individual thought, and with no concept that spare time might be a source of intellectual renewal, rather than the chance to play. As C. Wright Mills remarked, alienated from work, the average person is alienated from leisure.16 The generation after that grows up thinking of civilization as one of those old fashioned hierarchical things we were smart to get rid of, and the generation after that one will grow up never knowing the term existed. The specialization of knowledge is an even better example. While specialization itself is necessitated by technological advancement, the disconnected nature of knowledge results from the loss of a global view. We do not have "learning," we merely have "information," because the ideals of having a civilization are missing. Students are not taught to have an inter-related world view, but to cram bits of knowledge into their heads so that they might find a job. The University ceases to be a "little universe," but becomes a honeycomb of specialized interests, and increasingly the pet project of industry. In turn, knowledge becomes even more specialized under the demands of meeting the burden of the already overly specialized fields. Thus, the loss of civilization becomes a "snowball" effect. Ultimately, however, Schweitzer traces the original core of the snowball back to the failure of 19th century philosophy.

"Ethics and Civilization," Part II of The Philosophy, is a survey of Western ethical thought (Socrates to Schweitzer himself). The survey of ethical thinking is crucial because, in Schweitzer's view, civilization is primarily an ethical matter, thus, he must explain its failure in terms of an ethical failure in Western thought. Throughout Western history, but especially in the 19th century, thinkers had tried to ground their ethical axioms in metaphysical systems, or in an understanding of the workings of the world. But, axioms based on these principles never succeeded in achieving any sort of consensus, or withered away with the systems upon which they were based. A mere understanding of the world fails to connect the axiom to any principle of grounding, and stems from the failure to achieve a metaphysical system. Metaphysical systems, however, only succeed in creating a dualism; subjecting experience of life to knowledge of the world, or abstractions which subjugate reality to the dictates of the system. Thinkers such as Hegel and Fichte tied ethical thinking to their systems so closely that, in Schweitzer's view, when those systems collapsed, ethical theory went with them (3).

Fichte, Hegel, and other philosophers, who for all their criticism of rationalism, paid homage to its ethical ideals, attempted to establish a similar ethical and optimistic view of things by speculative methods, that is by logical metaphysical discussion of pure being and its developing into a universe...doing violence to reality in the interest of their theory of the universe...Since that time the ethical ideas on which civilization rests have been wandering about the world, poverty-stricken and homeless...The age of philosophical dogmatism had come definitely to an end, and after that nothing was recognized as truth except the science which described reality. Complete theories of the universe no longer appeared as fixed stars; they were regarded as resting on hypothesis, and ranked no higher than comets (4).

(103). When the idealist systems collapsed and their ethical valuations went with them, the resulting vacuum was filled by the only metaphysical system still standing, that of scientific reductionism.

There were attempts at constructing a "scientific" ethics, biological and sociological.These attempts Schweitzer denounces as absurd, "there is no such thing as a scientific system of ethics, there can only be a thinking one." Thus, Western thought was left with an outlook which was pessimistic in relation to understanding anything beyond the mere physical workings of the world. For Schweitzer, this attempt at constructing "biological ethics" is symptomatic of the cynical approach of modernity itself.

Though pessimistic, modernity garbs itself in the disguise of optimism; a hallow, empty technological optimism based purely on control of the material conditions of life and a relationship to "things," (96-97). It is a pessimistic view because it gives up on an understanding of life, and despairs of knowing anything save the mundane aspects of control within the immediate material world. It substitutes instead, mere manipulation for actual understanding, "information" for real knowledge, and buying power for freedom. The false optimism of modernity is the essence of one-dimensionality. The result is the notion of civilization which we know today, the technical production of civilization's infrastructure, the world of "modern convenience," the thing Gilligan and the cast-aways wanted to get back to when they spoke of "getting back to civilization." In this sense the 1939 world's fair mentality, which predicted the brightest future for humanity based on technological fixes for everyone, was the most pessimistic view in human history. The view of civilization which seeks domination over nature is, in reality, a counterfeit notion of civilization, one which wearies the happy persona of material convenience and prosperity over a nature mired in despair.

Just as civilization is primarily ethical, so Schweitzer argues that the state of ethical theory in his day reflected the pessimistic roots underlying the er zots notion of civilization. What he had reference to, in 1923, was the rise of "emotivism" with G.E. Moore, at the turn of the century. Emotivism tried to rid ethics of its "emotive" aspects and to replace them with "scientific" ethics. One of the emotive aspects being replaced was the concept of morality. Schweitzer had also seen the early rise of linguistic analysis. In the decades that followed the publication of the Philosophy, the linguistic analysis of Year and Dewey brought in a purely descriptive form of ethical theory; normative ethics were dismissed as "outmoded." The situation today has not changed radically since the emergence of the descriptive trend. While there are normative ethics being done, especially in areas such as medical ethics, animal rights, and feminist ethics, and while many ethicists still try to ground their axioms in one principle or another (reason, nature, etc.) there is no common consensus. Then, there are the Derridians, who feel that any sort of grounding principle is, a priori, impossible and even oppressive. The pessimism of the Derridians and the "negative" side of postmodernism is a logical conclusion to that of modernity. Postmodernism, for good or for ill (and it is both) stems largely from a disillusionment with modernity. This pessimism is reflected in Derridian based versions of postmodern ethical theory.

The works of Richard Rorty are a prime example of this pessimism. Like Schweitzer, Rorty is disenchanted with metaphysical idealism. Rorty wants to present the notion of a "liberal utopia" free from the cruelty of the past; ethical, open, and democratic, and based, not upon the logocentric clap-trap of the past, but upon a Derridian reading of social need. He determines that since there are too many good descriptions of the world, and since no one of them can gain leverage enough to be privileged as truth, there is no truth.17 Since there is no truth, there is no telos to move toward. Therefore, one should simply mouth the bromides of the community while holding fast in one's heart the realization that all ethical values are false. Values are merely metaphors for lack of truth; or for the desires and will of the community. No thought is given to the nature of the community, to its justice, or lack there of.18 When confronted with the charge that he is merely relativizing ethical judgements, he answers: "...My strategy will be to try to make the vocabulary in which these objections are phrased look bad, thereby changing the subject, rather than granting the objector his choice of weapons and terrain by meeting his criticisms head on" (when the subject is saying something Rorty likes, it becomes "she--" obsessively).19 While he does stipulate that the beliefs of his "utopia" would be fostered by "free and open encounters" and that cruelty would be abolished, (along with religion of course) he also stipulates that "what comes to be believed" in the community would define the nature of truth.20 While this is no different from the current socially constructed reality, in which "truth" is "what has come to be believed," Rorty puts a spin on it which takes his "utopia" a step further into barbarism. "To see one's language, one's conscience, one's morality, and one's highest hopes as contingent products, as literalizations of what once were accidentally produced metaphors..." defines truth seeking in the "liberal utopia."21 In this context he is not simply speaking of being open minded, he is talking about giving away our most cherished self-definitions and sense of personal telos.

Rorty's views, while not intended to be representative of the current state of ethical theory, seems to be symptomatic of modernity's one-dimensional thinking. First, he closes the realm of discourse around the social project, maintaining his "liberal utopia," to the point that all truth and value is a mere function of the desires of "the community" (whatever that is). Secondly, he states that in his utopia no one would compare competing values to determine their moral worth, because, after changing the "vocabulary" "there will be no way to rise above the culture, language and institutions, and practices one has adopted and view all these as on a par with all the others."22 (Italics mine). Presumably, this means limiting discourse to the immediate localized community, with no reference to a larger tradition, since truth is merely the metaphor of communal desires, and no larger tradition posses anything we need in the way of "truth;" in other words, what Marcuse calls "a closed realm of discourse," the basic condition of one-dimensional society.23 Moreover, Rorty goes on to quote Donald Davidson as saying that one cannot look beyond language and culture.24 Rorty bends this quotation out of context, to imply that there is no need to compare competing values, because all values are mired in the same social constructs (therefore, capitalism is socialism, black is white, good is evil, ect.).Of course, Davidson is speaking of the necessity of language to thought (no intentionality of the speaker--Derrida's argument in Speech and Phenomina), while Rorty is speaking of imposing a particular social agenda through the manipulation of his vocabulary--which amounts to little more than a subtle Orwellian manipulation of thought, which is then defined as "free exchange" because it occurs within Rorty's blessed community. And what of the nature of the community, what if it is a fascistic community? No doubt, after the advent of "Rortyspeak" that will no longer be a danger.25

Schweitzer offers an alternative to such cynicism, one that is heavily dominated by three influences: Nietzsche, Schoupenhouer,26 and the 18th century philosophes. While he was a Christian theologian, he is able to embrace such a strange collection of interests because his theology represents the best in an otherwise problematic revisionary tradition, that of 19th century German liberalism.27 Thus, he combines the life-affirmations of Neitzsche with the ego purging of Schopenhauer. He jettisons the Dimonic fury of Neitzsche, and the life-escaping tendencies of Schopenhauer. Thus, in a sense, he creates a positive and selfless Nietzschian Ubermenche.28 From the 18th century he takes a love of reason as framed by a love of nature (nature=reason, "natural light") which is the cornerstone of an elemental thinking that results in his own "nature mysticism."29

But, the philosophical outlooks which he struggles against are Hegelian idealism and scientific reductionism. Schweitzer loved science, and undertook some scientific study in his youth (he did become a doctor). What he opposed, however, was the fragmentation of science into a reductionistic attitude which ignored a global philosophical view, and which reduced the experience of human being to mere description of the world. For Schweitzer, ethical thinking must proceed in an "elemental way," from "life-view" to "world view "(221-235). "Dr. Schweitzer himself defines worldview (`Weltanschauung') as the sum-total of the thoughts which the community or the individual think about the nature and purpose of the universe and about the place and destiny of...[humanity] in the world."30 While he embraces the search for a weltanschauung, he is concerned that world view be predicated upon "life view" rather than upon a theory of knowledge. The mistake he finds again and again in Western thought, as with Hegel and the idealists, is to try and base too much upon epistemology and metaphysics. World view is given in life-view. But, Western thought has tried to work things the other way around, to predicate a view of life on the metaphysical structures of its world-view. (75-77). The subjugation of life-view to Weltanschauung creates several problems for ethical thinking, and for civlization.To predicate the view of life (that is, one's understanding of his/her own life, its purpose and goals, in relation to the context or his/her life-world) upon a metaphysical world-view, is to impose preconceived categories upon reality.

Even though he never used the term "phenomenology," he demonstrates a phenomenological attitude, which can be seen in the development of his understanding of religious experience which eschews abstraction and systematizing, and proceeds from an attempt to allow the phenomena to suggest their own categories out of the experience of human being in concert with nature. "The Essence of Being, the Absolute, The Spirit of the Universe [Hegelian] and all similar expressions denote nothing actual but something conceived in abstractions which for that reason is also absolutely unimaginable. The only Being is that which manifests itself in Phenomena" (4). Schweitzer's ethical thinking was derived from this sense of "phenomenological oppression" of the "will to live." Knowledge derived from the will to live is rooted in our experience as human being, and thus should allow reality as we perceive it to dictate the categories of thought to us. "My knowledge of the world is a knowledge from outside, and remains forever incomplete. The knowledge derived from my will-to-live is direct, and takes me back to the mysterious movements of life as it is in itself" (282). In order to avoid the mistakes of idealist systems, ethical thinking must "not lapse into abstract thinking, but must remain elemental, understanding self-devotion to every form of living being with which it can come into relation" (307). Schweitzer's "elemental thinking," proceeds from one's own inward experience of the will-to-live, turned outward toward a "reverence for life." The term "will-to-live," which is a Schpenhaurian term, sounds as though it refers only to the struggle of an organism for its own survival, but, even though it is rooted in this notion, Schweitzer turns it outward, toward concern with the survival of others. It is an optimistic and intuitive (pre-cognative, pre-given) sense that life is important, has meaning, and can be approached through goodwill, toward the betterment of all life.

The will-to-live prompts an attitude of affirmation of all life, through an immediate organic connection (280). The will-to-live can remain on the level of struggle for survival, in a pessimistic outlook, but it can also be taken to a higher level through the recognition of life in the midst of all life. He rejects as arbitrary first principles such as Descartes' Cognito, but instead, grounds his ethics in an "immediate" and "comprehensive" fact of consciousness, "which says, `I am life which wills to live, in the midst of life which wills to live.' This is not an ingenious dogmatic formula. Day by day, and hour by hour, I live and move in it...Ethics consists in my experiencing the compulsion to show to all will-to-live the same reverence as I do to my own" (309). Thus, in order to turn outward toward others the urge to protect the will-to-live, Schweitzer does not resort to some means of abstract logical or metaphysical first principle, but he begins with an organic sense of reality. There is an urge to protect life, there is compassion toward others, these are pre-given, pre-cognitive realizations. When we do start to think about them, however, they form the basis of a morality. "There we have given us that basic principle of the moral which is a necessity of thought; it is good to maintain and encourage life, it is bad to destroy life or to obstruct it," (Ibid.).

The seeds of reverence for life must be cultivated, as they grow through society, by means of civilization. In so doing, the civilizing tendencies of reverence for life levin the culture, through a higher application of life-affirmation. Since protection of life involves a desire for the individual to flourish, quality of life must be protected as well. The highest quality of life involves freedom, and the opportunity of the individual to be fulfilled. Thus, reverence for life is expanded to form the basis of a social philosophy. It promulgates values beyond those of mere survive, such as peace, freedom, and social justice: Schweitzer was perhaps the first philosopher to support a philosophical basis for animal rights, and he castigates all of Western philosophy for not "taking animals seriously."31 He supported a reverence for nature, which furnishes the basis for an ecological outlook, and he saw domination of nature as the product of the counterfeit notion of civilization (333).32 Finally, he denounced the thinking of his time which saw people of color as less than fully human and fully deserving of all the rights of humanity. Schweitzer understood this failure to overcome the bigotry of the past as the result of civlization's demise, (The Decay, 32). He argues that civilization is not merely the privilege of an elite, and that the masses do not exist simply to provide the elite with the obtainment of their goals. Through a progressive approach to reverence for life the principles of the highest quality of life and human dignity are extended to all people (335).33 Thus, Schweitzer's social agenda culminates in reverence for life as the basis for solidarity with the poor and the worker, and perhaps an approach to some form of social democracy (he does hint at this, but does not spell it out) (Ibid.).

The immediate connecting link between an ethics of life-affirmation and a social agenda is the "outmoded" twin combination of civilization and "progress." This is a dangerous pair. In Schwetizer's day it had come to mean tearing down the natural world and imposing mechanical and human-structures upon all of life; these terms, "civilization" and "progress" came to justify everything from the exploitation of the worker, to the ecological devastation of urban sprawl. These twin values are the bain of the ecology movement, and they are the epitome of everything Schweitzer was against, but of course, not the way he uses the terms! It should be clear by now what he meant by "civilization;" the ethical content of the struggle to improve life on every level, form physical survive, to artistic freedom and moral excellence. The links from life-affirmation, to civilization, to social agenda run like so: life affirmation equals affirmation of quality of life for others, the struggle to improve and obtain such quality creates the affects of civilization, and civilization itself secures the goal of a social agenda because it is, part and parcel, the building of a way of life in which the values of human dignity, freedom, etc. are being cultivated. These values are being cultivated, or we do not have civilization. They are cultivated through the exercise of civilization upon culture, both in its popular and "higher" forms. Schweitzer is saying, if we have civilization, and we are aware of what it means, we are working on making things better for people; "making things better" includes not only housing and jobs, but also voting rights and political involvement, as well as symphony orchestras and artistic exhibitions, because these improve the quality of life, and they are expressions of our search to come to terms with our human being.

Progress in the Schweitzerian sense means, not flush-toilets or imperialistic expansion of markets, In the 19th century, progress came to be conceived of as a rumbling fright train which ploughed under everything anyone could care about, as it moved inexorably toward some undefined, lofty, abstract goal; in the film version of H.G. Wells' Things to Come, the tortured denizens of a "Buck Rodgers" style future utopia howl "how long must we endure this progress? Wont you let mankind rest?" (this is just before the first manned trip to the moon is made in a giant bullet fired from an enormous cannon--supposedly in the 21st century). Progress came to be seen as a rationalization for the bad effects of development, when woods are destroyed for the sake of freeways, "well, that's progress, you can't fight progress." "Progress," in Schweitzer's view, is not an inevitable march toward some ill-defined state of affairs which no one wants and which makes everything "perfect" by making life unlivable. As Simone Weil point out, the image of progress which views its inevitability as economic expansion comes, not from an ideal, but from the necessity of expanding economic production, which is itself necessitated by the need to constantly diversify production and therefore labor.34 Economic expansion is confused with civilization because it involves expanding the infrastructure of civilization, which is all that is left of the concept after reductionism. The infrastructure of civilization [the er zots civilization--material production] is a necessity, a practical result of organized living conditions, but it must be thought of only as one means of mediating the concept of civilization, not a substitute for the thing itself, and it must be curtailed to accommodate nature. Nor was Schweitzer trying to lay out a grand theory of history, his use of the term "progress" does not imply an inevitable telos, no "footprints of God in the sands of time."

Progress was, for Schweitzer, the development of an understanding of life-affirmation which constantly seeks to expand the concept and work out its meaning on a higher level [i.e., as we move from the rudimentary level of physical survival, to the "spiritual" level, freedom, artistic expression, and making these things part of our world view and available to everyone--we are making "progress"]. Schweitzer believed that the organic connection of this elemental thinking, the basis in experience of life-affirmation, was a more solid foundation than had been attempted in Western thought since the enlightenment. He defines progress in civilization as "supremacy of reason over the dispositions of men" in the struggle for life. By that, of course, he means moral supremacy, not megalomaniacal control (the Decay, 41). He admits that the relative progress we accrue in the struggle to survive over the conditions of nature brings with it also disadvantages of putting us at odds with nature (Ibid.). The "supremacy of reason"35 is the ability of life-affirmation to mitigate conflict and to secure peace, (Ibid.).

Schweitzer mediates his view of reason with a realization about its shortcomings. Like the early 19th century romantic opposition to the Aufklarung and to rationalism "we can see...the world dominated by a barren intellectualism, convictions governed by mere utility, a shallow optimism,...in a great deal of the opposition which it offered rationalism, the reaction of the early 19th century was right..."(Decay, 78). As we are children of both romanticism and the enlightenment, we still view rationalism as arid, and from the enlightenment, we cling to a shallow optimism based upon our understanding and manipulation of the physical world. Rationalism, for Schweitzer, was not the stolid enterprise the romantics made it out to be, but it had to be tempered with life-view. Rationalism, for Schweitzer, must involve a passionate living out of insights gained from the phenomenological attitude of live-view amid a rational framework of world view.36 An appropriate image for Schweitzer's notion of the failure of rationalism might be taken from Goethe's Faust, part II, where the workmen set to building an earthly paradise with picks and shovels. They set out to build a new world with primitive tools which were little better than anything previously known. Like those workmen, rationalism laid a good foundation with the first implements it found, but when it became apparent that the task was too great, and a finer set of tools was needed, it refused to seek anything else. Rationalism purported to interpret the world based purely on reason alone, yet it refused to venture into any territory beyond that which could be established by its own procedures and assumptions. When confronted with an avalanche of questions it couldn't answer, rationalism became overwhelmed and gave way to escape into romanticism and then idealism (Decay, 80).

The crucial role of reason and progress in Schweitzer's theory are their relation in building "world view." His entire analysis of the loss of civilization hinges on the assumption that we have lost the capacity for world view and have began to think that we can get along without one, or that we do not need one which embraces anything more grandiose than utility. Worldview is essential in restoring civilization, because we are, as a society, ultimately limited by the world view in which we live. World view is the conceptual limit upon our ability to infuse into society an attitude of struggle toward civilization. "That world view is optimistic which gives existence the preference as against non-existence and thus affirms life as something processing value in itself. From this attitude to the universe results the impulse to raise existence...to its highest level of value. Thence originates activity directed to the improvement of living conditions of individuals, of society, of nations and of humanity, and from it spring the external achievements of civilization..." (Decay, 83). As C. Wright Mills observed, the loss of rational capacity handicaps people in thinking about the goals and ends of their lives; people come to live for nothing more than the role of "cog in the machine" (op. cit.). So Schweitzer ends The Decay, and again ends The Philosophy with the argument that, in order to re-claim civilization, individuals must once more take up the question of the ends and goals of their lives. In other words, and he puts it in corny fashion, "we must think about the meaning of life" (82).

Of course, this question is going to be played out in light of metaphysical assumptions; but it is only in contemplating the nature and "meaning" of life that we can formulate an understanding of how our lives, both individual and communal, fail to serve the good, both for ourselves as individuals and as members of a community, and to understand how our lives have been circumvented and rooted into the good of an uncaring and pointless system. Our lives are lived in service to a false utility, one which only seeks the temporal security of an elite, and which replaces reason with mere rationalization about the role we play in maintaining that system. It is only through returning to an understanding of human being and communal being that we can free ourselves from this technological serfdom. This is the rudimentary beginning of world view. Reason is essential because it motivates and elevates the line of thought from mere rationalization to real searching. The notion of progress is essential because it provides the connecting links from the lot of one person that of society, and from the notion of survive alone, to that of quality of life.

While Schweitzer clearly thought in terms that employ all the modernist buzz-words that are bound to open problems in the current Postmodern climate, "reason," "progress," "civilization," etc., he was not nieve or unsophisticated in his use of these terms. He understood the limitations of reason, the pretense of rationalism, and the tendencies of humanity to construct rationalizations which justify its frailty. Nor does he use these terms in the way that most Postmoderns object to, "civilization" is not lionized environmental destruction or imperialist expansion, "reason" is not a mask for the pretense of an "all-knowing" hierarchy with an imposed agenda, and "progress" is not an inevitable march toward some pre-set metaphysical goal. In a certain sense reviving Schweitzer's view can be accomplished through a change in vocabulary. Rather than "progress," one might speak of "change," or opening up possibilities. The concept of progressive change in Schweitzer's view is not necessarily in a temporal direction, but moves from a more basic level of survival to a "higher" level of "spiritual" accomplishment. Progress is not a movement of history toward a goal, but the movement of society toward dealing with loftier questions and furnishing more sophisticated needs. This does assume, of course, that aesthetic and ethical "needs" are somehow "higher," as though they are more than mere accidental constructs but exist already and await fulfillment. That implies a certain take on human nature, and it means that reason serves a crucial function because human nature is such that reason is its orbitor. All of this smacks of a kind of metaphysical assumption many today are unwilling to make.

Schweitzer was, after all, a child of the enlightenment, and of the 19th century. By all standards, his ideas are "outmoded" and "quaint:" his praise of reason is truly a praise of reason, logocentric and rational. His notion of progress is progressive, and assumes that certain states of affairs are to be valued, others dissolved. His notion of civilization does require idealistic assumptions; on the whole, Schweitzer's view does require one to say that some things are better than others. There is no way around this reality, and if that is enough to kill Schweitzer's project before it can be re-born, that is probably the way he would have it, rather than pretend that it is just more pre-Postmodern language game in modernist garb. Moreover, there are even bigger problems with Schweitzer's view than his 19th century roots.

First, one might argue that all this talk of life-view and will-to-live is fine, but the link from one's own will to live to the externalized desire to protect the will-to-live of others fails to furnish a real grounding for an ethical system, to the same extent that any other basis in grounding has failed. Even more tenuous is the link from protecting will-to-live, to a full blown social agenda. By the time we are dealing with actual social policy, many re-interpretations can take place. One person's social betterment is another person's Orwellian nightmare. There is no guarantee that all members of society are going to agree on the nature "letter living," at Schweitzer's "higher level," and there is every reason to think they wont. Secondly, one might ask, is not this not merely a case of the saint asking everyone else to be a saint? Nevertheless, the alternative seems to be staying on the course which is rapidly transforming this planet into an environmental hell with the growing possibility of wars of mass destruction. In any case, Schweitzer might be viewed as just a starting point, a springboard to new directions, and a point of departure for re-examination of our assumptions about the goals and ends of our social existence.

It is easy to dismiss Schweitzer, his ideas really are based on the assumptions of a by gone era. His notions of nature could easily be taken to task by the Derridians, because they are undermined by other statements about controlling nature for survival. His notion of civilization assumes enlightenment notions of reason, and human nature. Moreover, our society is far too jaded to sit around thinking about the "meaning of life," we prefer our lives to be meaningless, and we work at making them appear that way. Schweitzer himself was aware of this, and expressed the notion, in Out of My LIfe and Thought, that his ideas would be forgotten because he was working against the spirit of the age. Nevertheless, as he puts it in The Decay:

But, perhaps it may be objected, we shall end in the resignation of agnosticism, and shall be obliged to confess that we cannot discover any meaning in the universe or in life. If thought is to set out on its journey unhampered, it must be prepared for anything, even for arrival at intellectual agnosticism....Still this painful disenchantment is better for it than persistent refusal to think out its position at all....There is, however, no necessity whatever for such an attitude of resignation. We feel that a position of affirmation regarding the world and life is something which is in itself both necessary and valuable. Therefore, it is at least likely that a foundation can be found for it in thought. Since it is an innate element of our will to live, it must be possible to comprehend it as a necessary corollary to our interpretation of life...we must strive together to attain a worldview affirmative of the world and of life...may become retempered, and thus become capable of formulating, and of acting on, definite ideals of civilization... (The Decay, 91).

This does not mean, however, that Schweitzer has nothing to offer. His notion of civilization is a point of departure, a place to begin thinking about the re-birth of civilization. In this context, there are two notions which are most crucial to consider: reverence for life, and the conceptual meaning of civilization. Taken together, they set up the realization that, however jaded, we are capable of being good to the other. We are capable of finding reasons to value life, and to find meaning in the over all scheme of things, even if we have to invent it (and there are those of us who think that we don't have to invent it). Civilization, then, is the struggle to free ourselves of encumbrances which would mire us in cynicism, and to work out the meaning of being good to others. Civilization is an organized playing out of that struggle, one which communicates itself, through the development of culture, to future generations who must come to understand the value of what has been gained and extend it into their own situation. The fear is that, having lost the concept, having reduced civilization to mere material convenience, humanity to genetic effects, and human experience to numbers, we might at worst lose the capacity to engage in this struggle, and at best, we wont be capable of taking part in it. The hope is, that by restoring the conceptual content of civilization, we might open the possibility of better things. Working out the particulars of what all of this means is the function of this journal, we invite dialogue.

Notes

1 He shaped the modern view of the historical Jesus. In the 19th century Christ was seen as a 18th century rational man, just a bright fellow who understood reason in way not unlike the way in which Voltaire or Kant understood it. Schweitzer realized that Jesus of Nazareth was rooted in a 1st century Palestinian context, and as such, saw his own mission as eschatological; it was the end of times, the Kingdom of God would soon manifest on earth, God would call the Romans to account for their oppression of the Jews, and the Jews to account for their faith, or lack thereof. In short, Schweitzer placed Christ in the milieu of an essene or zealot, whose mission was quasi-political, and based on the late hour in human history. This is still the basic historical view which dominates theology in the liberal protestant tradition, and which informs liberation theology. See In Quest of the Historical Jesus.

2 Albert Schweitzer, The Philosophy of Civilization. Translated C.T. Campion, Buffalo, New York: Prometheus Books. 1980 (originally 1923). The work is divided into two sections, the "Decay and Restoration of Civilization," and "Ethics and Civilization." Unwin has published the first section as an independent volume entitled The Decay and Restoration of Civilization. Because this is the main text used in this paper I am using parenthetical notes for that source, and documenting other sources as textual end notes.

3 Holtzmann was famous for the "Marcian hypothesis," the theory that the Gospel of Mark was written first, and that the others follow its basic plan and outline. This theory has become the standard outlook in Biblical scholarship, and is considered such a basic aspect of knowledge that the few scholars who still dare to challenge it are outside the mainstream view. Schweitzer's schooling was disrupted for a brief bought of military service. He took his Greek New Testament with him on maneuvers, and managed to do such valuable work that he made a major contribution to the synoptic problem, and earned the respect of Holtzmann, even though it contradicted part of his own theory. For all biographical information, see Albert Schweitzer, Out of My Life and Thought. New York: Mentor Books, originally published by Henry Holt and co. no copy right date given, the Post Script dates from 1932 and 1947.

4 Albert Schweitzer, The Quest of the Historical Jesus: A Critical Study of Its Progress from Reimarus to Wrede. New York: MacMillan, originally 1906, MacMillan paperbacks 1961, eighth printing, 1973.

5 Albert Schweitzer, Out of My LIfe and Thought. New York: Mentor Books, no date given, 69.

6 The word "spirit" is, of course, the German word giest--which is usually translated as "mind." But it can mean more than mind. Paul Tillich says that it refers to the total "dynamism of the individual." (see The History of Christian Thought). It is artistic, intellectual, and ethical sensibilities, and Schweitzer uses the term in all of these senses.

7 C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination.

8 find

9 Karl Marx, The Communist Manifesto. New York: International Publishers, 1948, 12.

10 Fewer U.S. Colleges Make English Majors Study Leading Writers," The Dallas Morning News, Sunday, Jan. 5., 1997, 6A.

It is not my wish to open this can of worms in this paper. The doctoral program in which I have been ensconced these past several years is one which prides itself on the trendy view point of multiple readings and alternate canons, so I am well aware of this kind of thinking. My main point is just that it is great to let new works into the canon, let's let everything in that we can, and it is fine to understand the notion of multiple readings, I don't have the only true reading. But, without an understanding of what came before, these concepts lose all meaning (and they will eventually lose their avant guard value). Moreover, we should not forget what came before, preserve the greatness of the past, while finding new greatness.

11 John Harris, "Universities for Sale," This Magazine (Sept.) 1991.

12 "Enemies of Public Education," Alisa Solomon with Deirdre Hussey, Village Voice Education Supplement, April 21, 1998, 2.

13 Ibid. 4.

14 "The Book on Bertlesmann," by Stacy Perman, with Andrea Sachs and Peggy Salz-Trautmann. Time, April 6, 1998, 54-56.

15 Edward Rothstein, "Nays and Ayes for Capitalism as Purveyor of Culture," New York Times, Monday, April 27, 1998,

16 C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination.

17 Richard Rorty, Contingency, Irony, Solidarity. Cambridge: Cambridge Univeristy Press, 1989, 4-5.

18 Ibid., 61.

19 Ibid. 44.

20 Ibid., 68.

21 Ibid., 61.

22 Ibid., 50.

23 Ibid., 50.

24 Rorty, 50.

25 Rorty has backed away from the position in Contingency, Irony, Solidarity, and has changed his tune quite a bit. See the book review in this issue, "Having his Cake and Eating it too," by Kevin Mattson. Nevertheless, has Rorty changed his tune because he really saw the problems with his book, or because the community is now mouthing a different set of bromides?

26 With the influence of Schoupenhouer, Schweitzer draws upon the thinking of the East, he especially liked Chinese thought, he was well read in a host of Chinese thinkers, and seems to like Lao-tse and schwan-tse the best. He was also well read in Indian thought.

27 Tillich traces the line from Lessing and the Socinians of the 18th century, through Strauss, Schleiermacher, to Weiss, Schweitzer, and finally to Baultmann. This tradition fought against a calcified orthodoxy and in favor of a liberal version of textual criticism. (Tillich, 292). It is very problematic in that it tends to be deistic at its roots, a charge most of its defenders might deny. As is reflected in this essay, Schweitzer's own view seems somewhat deistic, and almost in anticipation of the latter Whiteheadian style of process thought which came to be process theology.

28 Schweitzer never uses this term in connection with his own thinking, only as a description of Neitzsche's thought. He is not really trying to create his own Ubermenche, and lacks the aristocratic exclusion of Neitzsche.

29 He admires the French philosophes, and the British Minute philosophers. His favorite ethical thinker of the late 17th-early 18th century England is Schaftisbury, whose notion of natural goodness in connection with nature influenced the French, Dederoit, Condorcer, and others.

30 Campion, in Philosophy..., trans. notes, 68.

31 This quotation is found in the Philosophy, section, Ethics and Civilization.

32 "From our knowledge comes power over the forces of nature...by the power we obtain over the forces of nature we do indeed free ourselves from nature and make her serviceable to us, but at the same time we also thereby cut ourselves loose from her, and slip into conditions of life whose unnatural character brings with it manifold dangers" (333).

33 One way in which Schweitzer was not ahead of his time was in his total lack of consciousness in terms of women. He rarely even mentions women, and he writes in the vernacular of his day, so that in statements about human dignity for everyone, he invariably phrases it in a way that would be sexist in our day (dignity for "men"). But, one might easily extend the concept, women are, after all, part of life, and are possessed of the will to live.

34 Find

35 Schweitzer's love of reason, rationalism, and the enlightenment is not apt to win him much approval in the current Postmodern climate. And unlike the situation with the terms "civilization" and "progress," when Schweitzer uses the term "reason," he means pretty much "reason" as we understand the term. Nevertheless, his attitude toward reason is not as odious to Postmodern assumptions as one might think. He was not so nieve as to imagine that "reason" alone offered any sort of "objective" window on reality, and he agreed with the image romanticism painted of the results of rationalism as arid and barren and suppression of the inner life. But, for Schweitzer, those were the results of rationalism as it was practiced, not the limits of what reason might be for us if we understood elemental thinking. Schweitzer was a nature mystic, he saw reason as the foundation of a mystical journey, and he understood the limitations of privileging reason as the only orbitor of reality. (see the Decay, 74-84).

36 "And yet, although the two [reason and mysticism] refuse to recognize each other, the two belong to each other./it is in intellect and will, which in our nature are mysteriously bound up together, seek to come to a mutual understanding. The ultimate knowledge that we seek acquire is knowledge of life, which intellect looks at from without, and will looks at from within. Since life is the ultimate object of knowledge, our ultimate knowledge is necessarily our thinking experience of life. But this does not lie outside the sphere of reason, but within reason itself. Only when the will has throughout its relation to the intellect, has come, as far as it can into line with it,...is it in a position to comprehend itself...as part of the universal will to live and part of being in general...reflection, when pursued to the end leads somehow to a living mysticism...which is a necessary element of thought" (Decay, 81).

Read about my legs

Comments

2 comments:

This may be the first blog I run across that's longer-winded than mine, in both posts and comment threads. Actually, my posts are no longer long, although my threads can still get complicated.

A couple thoughts - obviously to disregard if the kind of responses you're getting are what you want.

Create shorter posts. For example, what about a summary of your article's main points? You could amplify according to what kind of comments you get.

Visit more blogs and start a blog roll - maybe you've already got that, I didn't check - for a greater variety of commentators.

It's good to run into another intelligent blog. Personally, I found it worthwhile to make mine more "reader-friendly."

This may be the first blog I run across that's longer-winded than mine, in both posts and comment threads. Actually, my posts are no longer long, although my threads can still get complicated.

A couple thoughts - obviously to disregard if the kind of responses you're getting are what you want.

Create shorter posts. For example, what about a summary of your article's main points? You could amplify according to what kind of comments you get.

I don't think the point of having a blog is to get comments. I like comments and I want them, but the point of the blog is so you can read my brilliant words, not vice versa.

the problem with the world today is the dumbing down of everything. People need to read more long hard to understand thought provoking articles, not more sound bites.

Visit more blogs and start a blog roll - maybe you've already got that, I didn't check - for a greater variety of commentators.

I have tons of ther blogs listed is that what it is?

It's good to run into another intelligent blog. Personally, I found it worthwhile to make mine more "reader-friendly."

no it sounds like you made it more unread person friendly.

Post a Comment