Originally Posted by Westvleteren View PostI had said that by historical critical methods we can corroborate the Gospels as historical evidence of Jesus' existence. I also laid out an extensive criteria for determining what is mythology and what is not. I didn't claim the Bible corroborates itself. There is obviously a method or no book could ever be corroborated. That method is called "historical critical method." This is so basic and these guys act like I made it up. They are practically saying there's no such thing as historical criticism. This more than more than anything else shows the Orwellian nature of atheism. Anything that they can't out argue by reason or historical fact they merely claim doesn't exist and make to go away because they don't like it. They just brain wash their mentions into thinking "there can't be such a thing as historical critical methods."

There is no method that allows the Bible to corroborate itself, as soon as you said that it nullified any possible argument you could make. Quite simply it is asinine. And no I could not care less that you are a PhD candidate as it has no bearing on the validity of your assertions.

Doesn't it seem really imbecilic to think that there's this one book that can't be corroborated? I used three different senses in which a book can be corroborated in order to show how foolish it is to make the statement "no method could exist that would do this." Each sense in which the Gospels can be corroborated (use the Gospels since the historical Jesus was the issue) I use another kind of book. Let's look at the three aspects of the historical critical method that verify the Gospels, and then at the criteria for understanding mythology from historically based writing. Three ways of corroborating the Gospels:

I. The authority of the teaching for the tradition

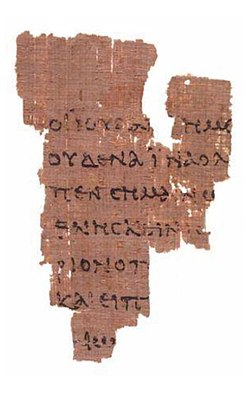

Most scholars point to the fact that the four canonical Gospels were already used by most of the church by the time of the canon[Martin Franzmann (The Word of the Lord Grows, St Louis: Concordia, 1961, 287-295)]. They bear the stamp of approval of those who were in charge of the teaching for the tradition. The problem is modern skeptics refuse to accept the facts, despise the truth, refuse to accept any sort of defense regardless of how good it is and basically refuse to even investigate the facts. If one actually examined the facts there is no way one can conclude other than that the four canonical gospels are the most logical choices of all the writings we have. Of the 34 lost gospels of which we have copies, fragments, theories, or any sort of inking only the four canonical Gospels makes sense as candidates for the canon. The Gospel according to Thomas has a historical core that probably goes back to the time of late first century. Yet it also has obviously late, maybe 3d century, heavily gnostic material. The Gospel of Peter had material that is corroborated as independent of the synoptic or of of John (see Ray Brown, Death of the Messiah) yet it encases this material in a clearly late framework. Only the canonical Gospels can be bore out as early dated, the trend is to even earlier dates, and at the same time has this vast body of attestation including the final inclusion in the canon. Skeptics also overlook the extent to which these 34 lost gospels supplement and corroborate the canonical Gospels. Most of the historical core of Thomas is in agreement with the synoptic.

American Theological Library Association

More than half of the material in the gospel of Thomas (79 sayings) is paralleled in the canonical gospels:

*

27 sayings are in Mark & the other synoptic

s; *

46 parallel Q material (in Matthew & Luke)* *

12 echo material special to Matthew; & *

1 is only in Luke.

* [Q parallels include 7 sayings where Mark has a variant version]

Thomas is important for synoptic studies for two reasons:

Form: It proves that collections of Jesus sayings with no narrative were known in the early church. Thus, it gives indirect support to the hypothesis of a synoptic sayings source, Q. *

Contents: Its version of some Jesus sayings is simpler than the synoptic parallels.

For the past 40 years scholars have debated whether Thomas is directly dependent on the synoptic gospels or not. Some have maintained the traditional view that Thomas is a 2nd or 3rd c. gnostic composition whose author extracted Jesus sayings from a Coptic translation of the NT & edited them to fit a gnostic worldview. Most recent experts on Thomas, however, regard it as an early sayings collection based on oral tradition rather than any canonical text.

There are four main reasons why scholars who have studied Thomas conclude that it is independent of synoptic tradition:

No narrative frame: If the compiler of Thomas drew these sayings from the canonical narrative gospels, he removed every trace of the stories in which the synoptic writers embed them. *

Non-synoptic order: If the compiler of Thomas drew these sayings from the synoptic gospels, he totally scrambled them, separating adjoining sayings & scattering them at random. No one has yet proven that the sayings in Thomas are arranged according to any logical pattern. *

Random parallels: Sayings in Thomas sometimes echo Mark, sometimes Matthew, sometimes Luke. There is no clear pattern of dependence on any one text. *

More primitive form: Sayings in Thomas are often logically simpler than their synoptic counterparts. If the compiler drew these sayings from the synoptic gospels, he edited out the traits characteristic of each writer. While some synoptic parallels in Thomas have gnostic embellishments, these are easily removed.

Together these traits of Thomas make it highly unlikely that any synoptic gospel was used as its source. In fact, the random, eclectic character of the contents of Thomas makes it a more primitive composition than the synoptic sayings source that scholars call "Q." While many individual sayings in Thomas may be of late gnostic origin, the core of the collection (sayings with synoptic parallels) is probably as old or older than the composition of the canonical gospel narratives (50-90 CE). To date this gospel any later makes it hard to explain the general lack of features dependent on the synoptics.(Copyright © 1997- 2008 by Mahlon H. Smith All rights reserved.)

[For more details see Crossan, J.D. Four Other Gospels (Sonoma CA: Polebridge Press, 1992) pp. 3-38 or Patterson, S. J. in Q-Thomas Reader (Sonoma CA: Polebridge Press, 1990) pp. 77-127.]

The old independent core of Peter supports the idea of guards on the tomb, meaning it also supports the crucifixion, the tomb, and the resurrection, empty tomb.

What this means for us so far is that the stamp of approval given by inclusion in the canon means several things:

(1) it means the church as a whole already recognized those books as valid based upon the teaching handed down from the Apostles through the Bishops.

(2) That is corroborated historically and can be verified by the extra canonical materials that agree with the readings, such as Thomas and Peter.

(3) The very fact inclusion in the canon is a priori testament to this fact, since apostolic affirmation was part of the criteria.

An examination of how the canon came to be will bear this out. This is written by me based upon the Franzman source above. It's found on my website Doxa> Bible> The Canon: how do they know the got the right books?

this was originally part ofa much longer work, to see the whole thing here's a link: https://religiousapriorijesus-bible.blogspot.com/2011/08/historical-validity-of-gospels-part-1.html