When I first began my PhD work t UTD I had a professor in oneof the frst classes I took there who lecturedon different wayso f knowin, It seemed intutative to me that there are different ways of knowing. I had not thought about it reallybut that prf had many ways.I feel two aresufficent, One can subdivide but there are two major categoroes. Actual frst hand experiemce and abstract learning. Or experoecimg vs "book learning." I think I can prove the Greeks made this distinction.

Returning to facebook I got several responses that idicate the atheists are pi to their old tricks, deying the personal dimension and tryimg to mae scentifc fact the standard of all knowledge.

On Face book I recieved this comment:

Boris Badenoff

"Joe Hinman There are not different ways of knowing. There's knowing and not knowing, that's it. Religious belief is not knowledge, it's not wanting to know."

Joe Hinman

Boris Badenoff no that is wrong. There are different ways of knowing. I know my mother loved me without doing a single truth table or vin diagram. You are trying to lionize your deal that you do so you will know it all.

Top fan

Boris Badenoff

"Joe Hinman You know your mother loved you because you had evidence if that."

Joe Hinman

Boris Badenoff it wasn't formal logic. there are different types of evidence and there are different ways to know.

The evidence of mother's love is experieced not communicated abstractly as in books. That dichotony itself proves different ways of knowing. He never answers this.

Boris Badenoff

Joe Hinman Nope. There are not different ways of knowing. Just knowing and not knowing.

Joe Hinman

Boris Badenoff yes they are love is feelings logic is not those are different they are both kinds of knowledge'.

He's just reguritating at this point.

Boris Badenoff

Joe Hinman Nope. Feelings don't produce knowledge. They produce beliefs and superstition.

I just proved they do prodice knowledge

I scientisemists are into this posiotion ofone form of knowig becausethey think of course scientific knwoing will domimate that will gve them power. It's an ideologcal postion.

Joe Hinman

to Boris Badenoff Yes it does, you know love because you feel. take it from those of us who do love. Your position is obtuse, It doesn't make you cool or smart, It's quite thick.

Joe Hinman

see my book on Amazon

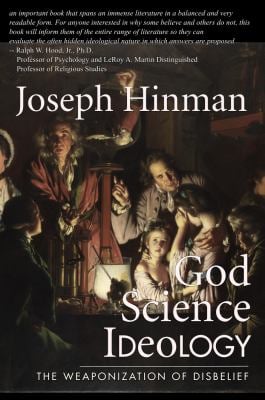

Joseph Hinman's new book is God, Science and Ideology. Hinman argues that atheists and skeptics who use science as a barrier to belief in God are not basing doubt on science itself but upon an ideology that adherer's to science in certain instances. This ideology, "scientism," assumes that science is the only valid form of knowledge and rules out religious belief. Hinman argues that science is neutral with respect to belief in God … In this book Hinman with atheist positions on topics such as consciousness and the nature of knowledge, puts to rest to arguments of Lawrence M. Krauss, Victor J. Stenger, and Richard Dawkins, and delimits the areas for potential God arguments.

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

Tuesday, July 05, 2022

My New book God, Science and Ideology is out!

This is a review of the book from Philosophy in Review Vol. 42 no. 2 (May 2022).

Joseph Hinman. God Science Ideology: Examining the Role of Ideology in the Religious-Scientific

Dialogue. Grand Viaduct 2022. 647 pp. $59.99 USD (Hardcover ISBN 9780982408766).

If any area of current philosophy is so incendiary as to teeter on violence, it is argument about an

omnipotent divine being’s existence. The ‘debate’—too gentle a term here—becomes so vehement

it echoes the doctrinal tree-shaking that led to so many religious wars. Certainly, professional

philosophers tend toward protocols of respect and charitability among one another. But the internet

has provided history perhaps the most immense battlefield for doctrinal dispute. Hinman’s lengthy,

vehement, if generally sober offering to this battle is almost definitive of the field.

It is likely one of the most thorough religious apologetics in contemporary times. It merits a serious consideration and is certain to draw some rabid fire. A quick thumbing through blogs, blog comments, message boards, and chat rooms reveals an astonishing, if not unsettling, anger, and even hatred. After centuries of highly Christianized Western philosophy, upon the advent of Darwin/Wallace theory, sides quickly started forming. While ancient Greece tolerated few atheists, such outlook had only shaky grounds until 1859: a magnificently cogent theory of life’s origins and development required no ultimate mover. It seems the religious have since then taken up arms, both metaphorically and, in the case of World Trade Center and its imitators, literally. In turn, growing atheist movements reacted against such defensive measures. For reasons beyond this review’s scope, this upsurge in side-taking and regrouping, like so many buffalo facing predators, evidences a powerful human need for settling the issue, pace the few agnostics gazing on bewildered. A peek at the arguments reveals a mess.

One of the advantages of Hinman’s new work is that it attempts, among other goals, to order the mess somehow. While he is professedly theistic, the work exudes care and some respect for the various perspectives. Its sheer breadth and depth of scholarship and capacity in articulating it attests the generally due respect of the many sides, which often exhibit the rational and irrational in one commentator. The central theme, which ties the various sub-arguments together, is that ideologies outside of the sciences themselves are informing science-based, evidential arguments about divine existence. Many sides of the debate, including the monotheistic, are equally guilty. Hinman’s ideology-scorning approach, in the end, exerts notable force and a new voice in the controversy. His book has brought together many positions in the debate. Hinman’s most persistent targets are the contemporary theories maintaining that a divine’s existence can be decided solely by scientific theories. Most thinkers, except possibly extreme agnostics, seem to harbor ideologies. Perhaps ideologies have their place somewhere in the life of the mind. That caveat, and whatever place ideologies may hold, are not the point here. Rather, it is that too many researchers in this area either do not admit their own ideology or deny its importance to the discussion of divine existence. Hinman details how many a contribution to the discussion is steeped in ideology, without their authors’ acknowledging—or even seeing—it. Only by bringing these ideologies explicitly into the discussion can it gain significant traction to get the discussion out of the mud.

see the rest: https://philpapers.org/archive/MILJHG.pdf

Copyright: © 2022 by the author. License University of Victoria. This is an open access article distributed under the terms and 22 conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license 4.0 (CC BY-NC) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

It is likely one of the most thorough religious apologetics in contemporary times. It merits a serious consideration and is certain to draw some rabid fire. A quick thumbing through blogs, blog comments, message boards, and chat rooms reveals an astonishing, if not unsettling, anger, and even hatred. After centuries of highly Christianized Western philosophy, upon the advent of Darwin/Wallace theory, sides quickly started forming. While ancient Greece tolerated few atheists, such outlook had only shaky grounds until 1859: a magnificently cogent theory of life’s origins and development required no ultimate mover. It seems the religious have since then taken up arms, both metaphorically and, in the case of World Trade Center and its imitators, literally. In turn, growing atheist movements reacted against such defensive measures. For reasons beyond this review’s scope, this upsurge in side-taking and regrouping, like so many buffalo facing predators, evidences a powerful human need for settling the issue, pace the few agnostics gazing on bewildered. A peek at the arguments reveals a mess.

One of the advantages of Hinman’s new work is that it attempts, among other goals, to order the mess somehow. While he is professedly theistic, the work exudes care and some respect for the various perspectives. Its sheer breadth and depth of scholarship and capacity in articulating it attests the generally due respect of the many sides, which often exhibit the rational and irrational in one commentator. The central theme, which ties the various sub-arguments together, is that ideologies outside of the sciences themselves are informing science-based, evidential arguments about divine existence. Many sides of the debate, including the monotheistic, are equally guilty. Hinman’s ideology-scorning approach, in the end, exerts notable force and a new voice in the controversy. His book has brought together many positions in the debate. Hinman’s most persistent targets are the contemporary theories maintaining that a divine’s existence can be decided solely by scientific theories. Most thinkers, except possibly extreme agnostics, seem to harbor ideologies. Perhaps ideologies have their place somewhere in the life of the mind. That caveat, and whatever place ideologies may hold, are not the point here. Rather, it is that too many researchers in this area either do not admit their own ideology or deny its importance to the discussion of divine existence. Hinman details how many a contribution to the discussion is steeped in ideology, without their authors’ acknowledging—or even seeing—it. Only by bringing these ideologies explicitly into the discussion can it gain significant traction to get the discussion out of the mud.

see the rest: https://philpapers.org/archive/MILJHG.pdf

Copyright: © 2022 by the author. License University of Victoria. This is an open access article distributed under the terms and 22 conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial license 4.0 (CC BY-NC) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)