Helmutt Koester

This is my contribution to a book Called Defending the Resurrection edited by J.P. Holiding. I urge the reader to buy it as there are many fine arguments made in it. Not all of this article was used. This is its original form it was changed substantially in several ways, such are the needs of editors.

Introduction

Skeptical machinations are endless, anytime the tide turns toward the apologist the skeptic will take a further step back and seek to change the ground rules in a fundamental way. So it is with the perennial resurrection debate since the tide was shifted by McDowell and then by Craig, years ago. One of the major tactics used by skeptics to change the ground rules has been to uproot all points of the compass so the apologist can’t get his/her bearings as to what events are actually historical and thus defensible. To accomplish this, the skeptic has partly pulled off a resurrection of his own, by resurrecting old ninetieth century clap trap that was dismissed ages ago. One of the major examples is the historical nature of the empty tomb. McDowell then Craig both did fine jobs of demonstrating that if the facts about the tomb are in place the debate goes to the apologist. But then the atheists used the Jesus myth idea, long disproved and discarded, to set up a new round of doubt about the historicity of the tomb. For skeptics today the four Gospels are not even factors, they are totally ignored as though they offer no evidence at all, and all that they proclaim is regarded as pure fiction. It is of paramount importance, therefore, to establish some historical facts about the case and to nail down some of the points of reference. In this department of points of reference pertaining to the narrative there can be no more important point of reference than the issue of when the story of the empty tomb began to circulate. This is a crucial issue for several reasons: (1) it’s the lynch pin upon which is hung all the empty tomb logic arguments of the major apolitical moves of the last fifty years. That means two things: (a) it would mean the writing is too early for the events to allow for development of elaborate myth; (b) it would mean that a large number of eye witnesses were still around, depending of course on how close to the events the writing could be placed. (2) The earlier the date the more it would undermine the Earl Doherty’s Jesus myth theories by distorting their time table. Thus in this article I will be focusing upon the one issue: when did the empty tomb story begin to circulate in writing?

There are a few assumptions that must be discussed up front. Why focus on writing if we can assume it was told orally first? Obviously whatever point at which the writing started, we can assume the material was orally transmitted before that point. Writing gives us a concrete means of pinning down a time frame. There’s no way to trace oral tradition as to when it began except in the most general of terms. But dating a text, however, we can be much more precise as to when the circulation began. The other major assumption that must be understood is that no one single individual wrote the Gospels. There were redactors and they came out of the communities and the communities are regarded as the authors now, not merely individuals. These communities of which I speak are those into which the earliest follows of Jesus began to group after the events which ultimately come to be represented in the Gospels. Each of the Gospels is taken by scholars today as representative of its own community.[1] So there was a Matthew community, a Mark community, a John community, and perhaps a Luke community, although I tend to attribute Luke to the Pauline circle as a whole and to the individual Luke himself. The problem this sets up for the Evangelical apologist is that it may open some other areas of conflict depending upon how deeply committed one is to an inerrant view of the Gospels. I have encountered atheists who just assert that redaction itself is proof enough that “it was all made up.” No serious scholar believes this and it’s simply a matter of understanding the more adult and sophisticated view to dismiss that bit of amateurish thinking. Yet accepting the liberal assumptions may create more problems for apologetics than it solves, this is a major issue that must be solved, and it must be solved it in the most decisive way. I will suggest solutions to the problems that are more evangelical friendly, and I assert these positions for the sake of argument, to show that even granting the assumptions of liberal scholarship the resurrection still enjoys the support of the evidence. Be that as it may my one overriding concern in this article is in proving that the resurrection circulated, in writing, by mid first century period. Therefore, I will be using the assumptions of liberal scholarship and the evidence of liberal scholars. My reason for doing this is to demonstrate that the case can be made not merely with materials from writers skeptics expect to take the conservative side, but with fairly liberal scholars who skeptics would expect to be skeptical.

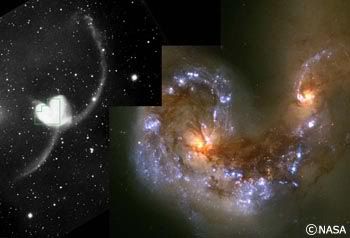

In order to understand what we need to answer we must first understand the skeptical claim. The major point undermining the historicity of the empty tomb is the argument form silence; the tomb is never mentioned as such in any of the epistles or any other early Christian literature until the middle of the second century. Dale Allison remarks: "Paul did not know about Jesus' grave, and if he did not know about it, then surely no one else before him did either. The story of the empty tomb must, it follows, have originated after Paul."[2] For certain kinds of skeptics that seems like a crushing indictment. It’s actually not as powerful as it seems since it’s only an argument form silence, and argument from silence doesn’t prove anything. The apologist is apt to answer that some of the passages in the Pauline corpus imply the empty tomb, even though they don’t actually speak of it directly. While these are good points, we can do better. There’s some pretty strong evidence that the story of the empty tomb was circulating, in writing, as part of the end to the Passion narrative as early as middle of first century. The great scholar Helmutt Koester argues for a conclusion of textual criticism that can be demonstrated by scholarly methods. The point he’s making is that all four canonical Gospels and the non canonical Gospel of Peter all share mutual connection to an earlier text that included the passion narrative and that ended with the empty tomb. He says:

"Studies of the passion narrative have shown that all gospels were dependent upon one and the same basic account of the suffering, crucifixion, death and burial of Jesus. But this account ended with the discovery of the empty tomb.[3]

[and again]

"John Dominic Crosson has gone further [than Denker]...he argues that this activity results in the composition of a literary document at a very early date i.e. in the middle of the First century CE" (Ibid). Said another way, the interpretation of Scripture as the formation of the passion narrative became an independent document, a ur-Gospel, as early as the middle of the first century![4]

He is talking in both cases about the original passion Narrative of “Ur Gospel” that he sees standing behind these five works. Here he tells us that this original work, this “Ur gospel” was circulating at the mid century point and that it contained the story of the empty tomb. Thus, the empty Tomb was part of the Gospel narrative as early as mid century. If we take the conventional accepted dates it was within 20 years after the original events. How does he prove this?

The argument Koester is making comes from another scholar named Jurgen Denker, a textual critic. The basic proof of the argument is the result of textual criticism. Textual criticism is a science. Though many on both sides of the fence, skeptics and apologists find textual criticism assailable, they both assume and use it when it suits them. The atheists who argue for Q as a proof that “it’s all made up” have to accept the validity of textual criticism in order to support the idea of Q. Evangelicals, who quote Josh McDowell talking about how the NT text is 98% reliable, are actually accepted whole sale the validity of textual criticism, because that is how such a figure is arrived at. The evidence of an Ur Gospel in the passion narrative comes from readings in several manuscripts which seem to date from periods much latter than the canonical Gospels. This is deceptive, however, because even though the texts are latter than the canonical gospels, the readings in the texts are much earlier. That sounds contradictory but it is not because the manuscripts (MS) are copied from earlier readings. The earlier readings leave traces of their original sources in the way they read. In other words if we had a book written in 1950 it would probably read like a 1950’s book. The speech, the form of the language, the slang would all be like the 50s. But suppose parts of that book were copied from a book written in Shakespeare’s time. In addition to the fifties slang you would have some parts that would read like Elizabethan English. Those parts would be easy to pick out and we would know that the author was either copying something old or trying to sound old. The situation with these MS is similar. For example one of them called “The Diatessaron” is an attempt by Tatian at making a harmony of the four Gospels. This attempt dates to about 170 AD. But some readings in the Diatessaron seem to from a much earlier time. So we know by this that they are copied form very early copies that were written in a more Jewish style.

There are a couple of other aspects of this copying phenomenon that need to be understood. First of all, one often hears conservatives saying things like “there is no textual evidence for Q.” The reason for that is that when Q was incorporated into the synoptic people stopped copying it and eventually stopped using it, because it was incorporated into a text that seemed more complete. Overtime the copies of Q rotted away and on one bothered to copy it further. Secondly, as to the assumption that redaction (which simply means “editing”) in and of itself is proof that “It was all made up,” this is manifestly wrong. The assumption is based upon the fallacy that no one could purposely combine two holy books without believing that they were not “inspired.” But the reason this is a fallacy in relation to the New Testament is because at the time the process of redaction on the Gospels started the redactors did not imagine that they were editing “the New Testament!” They were not regarded as holy books. While some might think that’s a green light to make things up, its’ also reason why they would not make things up, because while they did not have a concept that they were writing the Bible (thus no need to conjure up the fabricated essence of a new religion) it does not prove in any way that they had no respect for the truth. They were neither making up the Bible nor creating the rudiments of a new religion; they had no idea of either of those things. They were merely producing a sermonic document for the edification of the community. They intended these works to be read by people they were living with and perhaps to spread into a larger circle of those who worshipped with them. But they did not think of themselves as writing “the Bible.” The process is more analogous to a modern preacher writing a sermon for Sunday; he doesn’t want to fabricates thing that aren’t true, but he’s free to change certain aspects of the order, combine different portions of other “sermons” and place ideas in different contexts and create a document that will hold the audience’s attention and teach them things, but in so doing communicate truth and a story they already knew. No intention of “make things up” need be read into it.

This is not to say that the redactors did not have great reverence for the sources they used. They saw the prior sources as testimonies of holy men signifying holy truth, even if they did not see them as scripture. As we move up in time to the post apostolic age they have an ever greater reverence for anything that tells them about the origins of the faith and the words of Christ. Yet that doesn’t mean they thought of themselves as writing the Bible. They were free to quote and blend the quotes in with other quotes from other valuable sources, but not free to “make thing up,” not free to lie or fabricate. Thus we have the creation of the works we know as the canonical Gospels as “patch works” put together out of prior sources. They didn’t see themselves as producing the canonical Gospels, they saw themselves as accurately reflecting truth for the edification of their flocks, and pulling together the great sources of truth left to the church into their own little humble sermonic contributions. In so doing they left traces of early versions and as their products were copied some of those traces hung on and they continue to testify to us of the earliest roots of the faith. Several traces of these early documents, these lost “Ur gospels” show up in the latter works of non canonical gospels, some of which are tainted with Gnosticism. The famous Nag Hammadi find The Gospel of Thomas is such a work. While it is clearly set within a heavily Gnostic framework of the third century, some of the passages prove to be an early core some of which are thought to be authentically spoken by Jesus, some of which have been theorized as making up the Q source. While Thomas is Cleary Gnostic some very anti-Gnostic traces are left. The same process of redaction we see at work in the canonicals is also at work in the non canonical gospels. So we find traces of an earlier age. Of more direct bearing on the resurrection story is the non canonical Gospel of Peter.

Gospel of Peter and the Empty Tomb

The Gospel of Peter (aka “GPet”) was discovered in the ninetieth century at Oxryranchus, Egypt. It was probably written around 200 AD and contains some Gnostic elements, but is basically Orthodox. There are certain basic differences between Gospel of Peter (GPet) and the canonical story, but mainly the two are in agreement. Gpet follows the OT as a means of describing the passion narrative, rather than following Matthew. Jurgen Denker uses this observation to argue that GPet is independent and is based upon an independent source. In addition to Denker, Koester, Raymond Brown, and John Dominick Crossan also agree.[5] It is upon this basis that Crossan constructs his "cross Gospel" which he dates in the middle of the first century, meaning, an independent source upon which all the canonical and GPet draw. But the independence of GPet from all of these sources is also guaranteed by its failure to follow any one of them. Raymond Brown, who built his early reputation on study of GPet, follows the sequence of narrative in GPet and compares it in very close reading with that of the canonical Gospels. He finds that GPet is not dependent upon the canonical, although it is closer in the order of events to Matt/Mark rather than to Luke and John. Many Christian apologists think it’s their duty to show that GPet is dependent upon the canonical gospels, but it is basically a proved fact that it’s not. Such apologists are misguided in understanding the true apologetic gold mine in this fact. The fact that GPet is not dependent enables it to prove common ancestry with the canonicals and that establishes the early date of the circulation of the empty tomb as a part of the Jesus narrative. As documented on the Jesus Puzzle II page, and on Res part I. GPet is neither a copy of the canonical, nor are they a copy of GPet, but both use a common source in the Passion narrative which dates to AD 50 according to Crosson and Koester. Brown follows the flow of the narrative closely and presents a 23 point list in a huge table that illustrates the point just made above. I cannot reproduce the entire table, but just to give a few examples:

Helmutt Koester argues for the “Ur Gosepl” and passion narrative that ends with the empty tomb. He sees GPet as indicative of this ancient source. Again, the argument is not that GPet is older than the Canonicals but that they all five share common ancestry with the Ur source. There is much secondary material in Gpet, meaning, additions that crept in and are not part of the Ur Gospel material; the anti-Jewish propaganda is intensified, for example Hared condemns Jesus rather than Pilate.[6] Koester believes that the epiphanies (sightings of Jesus after the resurrection) are from different sources, while the passion narrative up to the empty tomb is from the Ur Gospel. It is on this latter point that he Differs with Crosson, who believes that the epiphanies were part of the Cross Gospel.[7] GPet was at first thought to be a derivative of the four canonicals but some scholars began to doubt this because it seemed like a collection of snippets from the four and as Brown pointed out, that’s not the way copying is done. Koester points out that Philipp Vielhauer following Martin Dieblius,[8] noticed that in GPet the suffering of Jesus is described in terms of the OT (though literary allusion) and lacked the quotation formulae (such as “he said to him saying” or “as it has been written”) which indicated that it came from an older tradition, since it would not be nature to take those out. Koester also points out that Jurgen Denker argues that GPet is dependent upon traditions of interpretation of the OT rather than it is the four canonicals, it shares these traditions with the canonicals because they all share the same prior source.[9] Crossan uses Denker and takes it further, they both see dependence upon Psalms rather than the canonicals as a sign of being earlier than the canonicals, but Crossan theorizes the date as mid first century. Koester says in describing it, “he argues that this activity resulted in the composition of a literary document at a very early date, in the middle of the first century,” (notice he does not say “around” mid century but “in the middle”).[10] He argues that the earlier source (the Ur Gospel) was used by Mark as well as Matthew and Luke and even John, as well as Gpet.

Koester agrees with Crossan and Denker about the passion narrative (what he calls the Passion Narrative—which includes the empty tomb) circulating early. He disagrees with three specific points none of which negates this basis thesis. The three points are these: (1) Reliability of the text (of Gpet) which comes to us from one latter fragment and could have been influenced by oral traditions and the canonical gospels as read by latter copyists. (2) Crossan believes that all the variations in Gospel tradition came from a core nucleolus of very early writings that form the cross Gospel and that is the basis of the canonical Gospels (combining a saying source (Q) with a narrative Gospel). But Koester believes that the oral tradition was still going up to the early part of the second century,[11[and that it was a fountain of information for various gospel writings all along the way. (3) Crossan holds that the epiphanies (resurrection sightings) were all from the Cross Gospel; Koester holds that they were from various sources. But none of them negates the basic core thesis which all three of them hold to, which is that the Ur Gospel passion Narrative includes the empty tomb and that it circulated early, perhaps mid century. Koester tell us his true opinion when the sates at the end of his list of these three problems:

“The account of the passion of Jesus must have developed quite early because it is one and the same account that was used by Mark (and subsequently by Matthew and Luke) and by John and as will be argued below by the Gospel of Peter, However except for the story of the discovery of the empty tomb, the different stories of the appearance of Jesus after his resurrection in the various Gospels cannot derive from one single source. They are independent of one another. Each of the authors of the extant gospels and of their secondary endings drew these epiphany stories from their own particular tradition, not from a common source.”[12]

What is he saying? First he is not disputing that the story of the empty tomb circulated early, he affirms it. He says “except for the story of the empty tomb” he means that is included with the original material, the other resurrection related sightings came from other sources.[13] Are those other sources fictional? In Koester’s mind they may be, but his conclusions are based upon the logic derived from the texts and the fragments of readings found in them, so they could be fictional or factual. They just don’t happen to be from that one original Ur Gospel; there’s noting in logic that prevents them from being part of other eye witness accounts. When he says the authors got these stories from their “own particular tradition” he means each of the communities that produced the individual canonical gospels has their own tradition sources, so these could well have been eye witness sources. Let’s bracket this for now and get back to it toward the end of the essay.

Koester sets out to demonstrate his first objection to Crossan by showing that the evolution of the gospel traditions were not set in stone and were fed by the oral tradition, I am not conserved with, but in so demonstrating he also illustrates one of the major arguments through which we know that there was an Ur Gospel passion narrative that preceded the canonical gospels. His argument against Crossan on the side point also serves to illustrate the major issue here before us in this essay. By “gospel traditions” he does not mean new fictional material was being made up, he means the way the story is told. By mid century how one told it was just as important as the content. The particular order, and traditions these were still evolving but were shaping up into a style and the style was being codified. That point is alluded to earlier where it is said that reliance on the psalms to describe Jesus suffering is earlier and that lack of certain kinds of quotation allusions are earlier than the canonical writing, that’s saying that telling it a certain way was forming up and when we see that formation not present that is an indication of an early source. When he says that Jesus’ suffering is described in terms of the psalms he is not saying the psalms gave them the idea of making up Jesus’ suffering. This is close to the idea of midrash. The Jews liked to tell things about history in terms of the Scriptures, it was like reinforcing the truth to show that what God is doing today unfolds in ways that allude to earlier acts of God. So they tell the story by making a bunch of literary allusions to the scripture.

Two such examples: the way Pilate speaks corresponds to Psalms and the response of the people to Jesus’ crucifixion is patterned after Deut. 21:8 in guilt of the people is expressed in tones that mock the prayer in the ritual:[14]

Matt 27: 24-25 Ps 26: 25-26

“so when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing….he took water before the crowd saying: ‘I am Innocent of this man’s blood, see to it yourselves.’ I hate the company of evil doers and I will not sit with the wicked, I wash my hands in innocence and go about thy alter, O lord.

“and all the people answered, his blood be upon us and upon our children.” “Set not the guilt of innocent blood in the midst of thy people O Israel.”

In acculturating these points Koester also, without explicitly saying it until latter, shows that no one would copy anything in this way. Ray Brown will make the same point as well and with a much more elaborate chart. Here are elements from one of Koester’s small charts that demonstrate the point; this deal with the mocking of Jesus after the trail before Pilate.

Gpete 3:6-9

And they put him in a purple robe Mark 5:17 they dressed him with a purple robe

Matt 27:28 they stripped him and put a scarlet robe upon him

Luke 23:11 they put a shining garment on him

John 19:2 and arrayed him in a purple robe

And sat him on the judgment seat and said judge righteously o King of Israel. John 19:13 and he sat down on the judgment seat

And one f them brought a crown of thorns and put it on his head Mark 27:15 /Matt 27-19 and plaiting a crown of thorns John 19:2 and the soldiers plaited a crown of thorns and put it on his head.

And others who stood by spat on his face Mark 14:65 one of the servants standing by struck Jesus with his hand

The supposition most skeptics will make is that the author of Gpete merely copies the existing gospels that were already known, changing a bit here and there to suit his own taste. The problem is there are so many allusions it’ clear the author was copying a tradition, and it’s a tradition a kin to the canonicals in some way, either as the common source they used or the canonicals themselves directly. No one copies in the way that it that it seems to have worked. No one would say “I want to talk about the purple robe so I’ll copy ‘they dressed him with a purple robe’ from Mark but I’ll say ‘put’ rather than dressed like Luke does.” No one copies by breaking down actual sentences from the difference sources and using a word from this and a phrase from that to make nuclear fragments like a sentence all the way thought the whole document. It could be that one would take a chapter from one and chapter from another and wedge in between still another segment from a third source, not for each and every sentence. This is a disproof of the idea that the author of Gpete merely copied the canonicals. No one copies this way. As Raymond Brown states in The Death of the Messiah:

GPet follows the classical flow from trail through crucifixion to burial to tomb presumably with post resurrection appearances to follow. The GPete sequence of individual episodes, however, is not the same as that of any canonical Gospel...When one looks at the overall sequence in the 23 items I listed in table 10, it would take very great imagination to picture the author of GPete studying Matthew carefully, deliberately shifting episodes around and copying in episodes form Luke and John to produce the present sequence. [Brown, Death of the Messiah,[15]

"IN the Canonical Gospel's Passion Narrative we have an example of Matt. working conservatively and Luke working more freely with the Marcan outline and of each adding material: but neither produced an end product so radically diverse from Mark as GPet is from Matt."[16]

Brown proves the tradition that Gpet follows is old and independent. It’s much less likely that the author of Gepet merely copied all his material form the canonicals. One copies an exegetical tradition, and that tradition by the time of Gpet (late second century) was already formed up in one way, and GPet shows examples of another form which should be considered earlier because it’s based upon the Psalms not upon Mark or Matthew. No one would copy in such a way as to instill all four from of the canonicals into the text, but traces of an original might be combined with latter works in that way. The arguments that Brown makes are elaborate, he presents several huge charts (no. 10 mentioned above). I can’t reproduce them here, but the marital is very important. The arguments Koester makes are extremely intricate. I do not have the time or space here to present these arguments because they take up whole books, but suffice to say many scholars, in fact the majority agree with Koester on these points. “Nevertheless, the idea of a pre-Markan passion narrative continues to seem probable to a majority of scholars. One recent study is presented by Gerd Theissen in The Gospels in Context, on which I am dependent for the following observations.”[17]

The issues are enormously complex and due to their complexity they lead to confusion when people try to argue and prove things. May of Koester’s statements have been misinterpreted by skeptics seeking to refute my use of his material merely because they don’t read the book or consider the context. I urge the reader to read Koester’s book, Ancient Christian Gospels, and Brown’s book Death of the Messiah, as Well as Crosson’s Cross Gospel.

"The Gospel of Peter, as a whole, is not dependent upon any of the canonical gospels. It is a composition which is analogous to the Gospel of Mark and John. All three writings, independently of each other, use older passion narrative which is based upon an exegetical tradition that was still alive when these gospels were composed and to which the Gospel of Matthew also had access. All five gospels under consideration, Mark, John, and Peter, as well as Matthew and Luke, concluded their gospels with narratives of the appearances of Jesus on the basis of different epiphany stories that were told in different contexts. However, fragments of the epiphany story of Jesus being raised form the tomb, which the Gospel of Peter has preserved in its entirety, were employed in different literary contexts in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew."[18]

The other major reason for assuming the earlier date for readings in Gpet, aside from the fact that no one would copy the synoptic the way the readings indicate it would have to be copied if it was based upon the synoptic, is that the reliance of these readings upon the OT indicates a stage of transmission prior to the development that would obtain after the synoptic. In other words, as said above, the story comes to be told in a certain way; even historically true stores develop hermeneutical traditions. When a reading demonstrates characteristics prior to that development, we know it was written earlier. The Synoptic do show some reliance on the Psalms. That’s because those are traces hanging on from the Ur Gospel that show up in the synoptic. The four canonical gospels and Gpet all use these readings as they draw from the Ur Gospel but they also use other readings and had Gpet been dependent upon the canonicals exclusively it would not show such total reliance upon the Psalms but would include a great dependence upon the canonicals. Brown’s charts prove this reliance of Gpet upon the Psalms and not upon Matthew or the other canonicals.[19]

Koester shows that the scenes of mocking Jesus were based upon Isaiah 50:6, Zach 12:10 and the scapegoat ritual are also brought into it. One can understand the meaning in drawing parallels between Jesus passion and the scapegoat of atonement for Israel. The robe and the crown of thorns are derived form the scapegoat ritual as well.[20] The Gospel of Peter reveals a close relationship between the mocking to the exegetical scapegoat tradition. He argues that these parallels are closer than those drawn between that tradition and the canonicals. He presents a fairly large chart to prove it. This compares seven examples between the scapegoat tradition, Gpet and all four canonicals.[21]

“It is evident that alone in the Gospel of Peter all three Items form the Isaiah passage appear together while John only includes the first and second (scourge and strikes) and Mark and Matthew only the first and third (scourge and spitting). Moreover, only the Gospel of Peter contains the same Greek terminology for scourging in agreement with Isaiah while Mark and Matthew substitute the common Roman term for this punishment only Isaiah and the Gospel of Peter mention the cheeks explicitly with respect to the strikes.” The piercing with the reed from the scapegoat allegory is preserved only in the Gospel of Peter while John has used this item for the piercing of Jesus’ side after his death; Mark and Matthew misread the tradition and change it to “strikes with a reed.”…the relationship of the Gospel of Peter to the parallel accounts of the canonical gospels cannot be explained by a random compilation of canonical passages. It is evident that the mocking scene in this gospel is a narrative version that it is directly dependent upon the exegetical version of the tradition which is visible in Barnabas.[22]

That tradition he argues is earlier than the canonicals by virtue of his greater adherence to the OT. The date of mid first century fro the circulation of the Ur Gospel with empty tomb is based upon old rule of thumb assumptions that textual critics always work by, ten years for copy time and ten years for travel time. In other words, travel time means the time it took for it to be copied and travel times mean the time it too to circulate to other places. Counting back from the 70, the standard assumption for the Date of Mark, twenty years is about 50 years. That is how Koester explains it.

[1]Stephen Neil, The Interpritation of the New Testament 1861-1961. London, NY: Oxford University press, 1964, 239.

[2]Dale C. Allison, Resurrecting Jesus: “The Earliest Christian Tradition and It’s Interpreters,” Journal for the Sutdy of Pseudepigrapha: supplement. T & T Cllark Publishers (September 30, 2005) 305-6.

[3]Helmutt Koester, Ancient Christian Gospels, Their History and Development. Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1990, 208.

[4] Ibid. 220

[5] Ibid, 218

[6] Ibid. 217

[7] Koester, find

[8] Ibid, 218

[9] Ibid.

[10]Ibid

[11]That’s based upon Papias reportedly saying he enjoyed hearing the voices of the great men speaking the words more than reading it on paper. That does indicate that there was some use or oral tradition at that time but if Papias was really old then he could have been referring to practice that had died out in his youth.

[12]Ibid, 220

[12] Ibid., 231 fn 3 he again clarifies his position from that of Crossan. Atheists reacting to material on my website where I speak of this habitually quote Koester assuming that the issue between him and Crossan is Koster’s objection to the idea of a pre Mark redaction that includes the empty tomb. That is not it at all. He makes It quite clear he agrees with that. The issue is entirely about how material after the initiation discovery of the tomb cam to be in the account, was it original (Crossan) or latter (Koester).

[14] Ibid, 221

[15]Raymond Brown, Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave, A commentary on the Passionnarratives in the Four Gospels. Volume 2. New York: Dobuleday 1994 1322

[16]Ibid. 1325

[17] Peter Kirby, Early Christian Writings, Website, URL: http://www.earlychristianwritings.com/passion.html last visited Jan 3, 2010.

[18] Koester, 240

[19] Brown, find

[20] Koester, 224-25

[21] Ibid, 226

[22] Ibid, 226-227