This is the continence of the issues on Wednessday. I laid out a major point

I. The authority of Teaching for the Tradition

II. Eye Witness Testimony

A. Community as Author.this leaves us with second sub point:

(B) Gospel behind the Gospels.

The Gospels we have now that we take for granted as the first and most authentic are constructed by communities, not individuals,(due to redaction, the editing process). They are composed from prior documents meaning that many of the very same reading were not the original words of authors named "Matthew, Mark, Luke, John" but already existed and already circulated in other forms. In other words, there are older "pre Gospel" Gospels. that can be dated as earlier as mid first century or so. We know this through a variety of sources.

The circulation of Gospel material can be showen in four areas:

(1) Oral tradition

(2) saying source Material

(3) Non canonical Gospels

The Great scholar Edgar Goodspeed held that oral tradition was not haphazard rumor but tightly controlled process, and that all new converts were required to learn certain oral traditions and spit them from memory.(4) traces of pre Markan redaction(PMR) (canonical material that pre-date Mark, assumed the to be the first Gosple)

Oral tradition in two major sources

(1) Pauline references to sayings

Two problems: (1) This does not confirm to a canonical reading; (2) it seems to contradict the order of appearance of the epiphanies (the sitings of Jesus after the resurrection). In fact it doesn't even mention the women. Nevertheless it is in general agreement with the resurrection story, and seems to indicate an oral tradition already in circulation by the AD 50s, and probably some time before that since it has had tome to be formed into a formulamatic statement.

An Introduction to the New Testament

By Edgar J. Goodspeed

University of Chicago Press

Chicago: Illinois.Published September 1937.

This web page is placed in the public domain by Peter Kirby and Wally Williams

Our earliest Christian literature, the letters of Paul, gives us glimpses of the form in which the story of Jesus and his teaching first circulated. That form was evidently an oral tradition, not fluid but fixed, and evidently learned by all Christians when they entered the church. This is why Paul can say, "I myself received from the Lord the account that I passed on to you," I Cor. 11:23. The words "received, passed on" [1] reflect the practice of tradition—the handing-down from one to another of a fixed form of words. How congenial this would be to the Jewish mind a moment's reflection on the Tradition of the Elders will show. The Jews at this very time possessed in Hebrew, unwritten, the scribal interpretation of the Law and in Aramaic a Targum or translation of most or all of their Scriptures. It was a point of pride with them not to commit these to writing but to preserve them.

example

1 Corinthians 15:3-8 has long been understood as a formula saying like a creedal statement.

For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures;

1Cr 15:4 And that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures:

1Cr 15:5 And that he was seen of Cephas, then of the twelve:

1Cr 15:6 After that, he was seen of above five hundred brethren at once; of whom the greater part remain unto this present, but some are fallen asleep.

1Cr 15:7 After that, he was seen of James; then of all the apostles.

1Cr 15:8 And last of all he was seen of me also, as of one born out of due time.

The problem with showing oral tradition is that we have to find it in writing and this is essentually impossible. But we do find references to it in Paul. We find the doxology and other sayings that to which he alludes.

The nature of the pericopes themselves shows us that the synoptic gosples are made up of units of oral tradition. Many skpetics seem to think that Mark indented the story in the Gospel and that's the first time they came to exist. But no, Mark wrote down stories that the chruch had told for decades. Each unit or story is called a "pericope" (per-ic-o-pee).(2)The nature of pericopes

On this basis Baultmann developed "form cricisim" because the important aspect was the form the oral tradition too, weather parable, narration, or other oral form.

Prof. Felix Just, S.J.

Electronic New Testament Educational Resources

pronounced "pur-IH-cuh-pee") - an individual "passage" within the Gospels, with a distinct beginning and ending, so that it forms an independent literary "unit"; similar pericopes are often found in different places and different orders in the Gospels; pericopes can include various genres (parables, miracle stories, evangelists' summaries, etc.)

Saying Source Material

Above we had oral tradition sources. The first one was Paul. This is about written saying sources. Again one of them is from Paul. But first "Thomas."

(1) Gospel of Thomas

The Gospel of Thomas which was found in a Coptic version in Nag Hammadi, but also exists in another form in several Greek fragments, is a prime example of a saying source. The narratival elements are very minimul, amounting to things like "Jesus said" or "Mary asked him about this,and he said..." The Gospel is apt to be dismissed by conservatives and Evangelicals due to its Gnostic elements and lack of canonicity. While it is true that Thomas contains heavily Gnostic elements of the second century or latter, it also contains a core of sayings which are so close to Q sayings from the synoptics that some have proposed that it may be Q (see Helmutt Koester, Ancient Christian Gospels). Be that as it may, there is good evidence that the material in Thomas comes from an independent tradition,t hat it is not merely copied out of the synoptics but represents a PMR.

(2) Pauline references

Quoted on Peter Kirby's Early Christian Writtings

KIrby quoting:Ron Cameron comments on the attestation to Thomas (op. cit., p. 535):

"The one incontrovertible testimonium to Gos. Thom. is found in Hippolytus of Rome (Haer. 5.7.20). Writing between the years 222-235 C.E., Hippolytus quoes a variant of saying 4 expressly stated to be taken from a text entitled Gos. Thom. Possible references to this gospel by its title alone abound in early Christianity (e.g. Eus. Hist. Eccl. 3.25.6). But such indirect attestations must be treated with care, since they might refer to the Infancy Gospel of Thomas. Parallels to certain sayings in Gos. Thom. are also abundant; some are found, according to Clement of Alexandria, in the Gospel of the Hebrews and the Gospel of the Egyptians. However, a direct dependence of Gos. Thom. upon another noncanonical gospel is problematic and extremely unlikely. The relationship of Gos. Thom. to the Diatessaron of Tatian is even more vexed, exacerbated by untold difficulties in reconstructing the textual basis of Tatian's tradition, and has not yet been resolved."

(Ron Cameron, ed., The Other Gospels: Non-Canonical Gospel Texts (Philadelphia, PA: The Westminster Press 1982), pp. 23-37.)

Kirby--In Statistical Correlation Analysis of Thomas and the Synoptics, Stevan Davies argues that the Gospel of Thomas is independent of the canonical gospels on account of differences in order of the sayings.

In his book, Stephen J. Patterson compares the wording of each saying in Thomas to its synoptic counterpart with the conclusion that Thomas represents an autonomous stream of tradition (The Gospel of Thomas and Jesus, p. 18):

(Kirby quoting Patterson)"If Thomas were dependent upon the synoptic gospels, it would be possible to detect in the case of every Thomas-synoptic parallel the same tradition-historical development behind both the Thomas version of the saying and one or more of the synoptic versions. That is, Thomas' author/editor, in taking up the synoptic version, would have inherited all of the accumulated tradition-historical baggage owned by the synoptic text, and then added to it his or her own redactional twist. In the following texts this is not the case. Rather than reflecting the same tradition-historical development that stands behind their synoptic counterparts, these Thomas sayings seem to be the product of a tradition-history which, though exhibiting the same tendencies operative within the synoptic tradition, is in its own specific details quite unique. This means, of course, that these sayings are not dependent upon their synoptic counterparts, but rather derive from a parallel and separate tradition."

Stevan L. Davies, The Gospel of Thomas: Annotated and Explained (Skylight Paths Pub 2002)

Lost Gospels

Koster theorizes that Paul probably had a saying source like that of Q avaible to him. Paul's use of Jesus' teachings indicates that he probably worked from his own saying source which contained at least aspects of Q. That indicates wide connection with the Jerusalem chruch and the proto "Orthodox" faith.

Parable of Sower 1 Corinthians 3:6 Matt. Stumbling Stone Romans 9: 33 Jer 8:14/Synoptics Ruling against divorce 1 cor 7:10 Mark 10:11 Support for Apostles 1 Cor 9:14 Q /Luke 10:7 Institution of Lord's Supper 1 Cor 11:23-26 Mark 14 command concerning prophets 1Cor 14:37 Synoptic Apocalyptic saying 1 Thes. 4:15 21 Blessing of the Persecuted Romans 12:14 Q/Luke 6:27 Not repaying evil with evil Romans 12:17 and I Thes 5:15 Mark 12:12-17 Paying Taxes to authorities Romans 13:7 Mark 9:42 No Stumbling Block Romans 14:13 Mark 9:42 Nothing is unclean Romans 14:14 Mark 7:15 Thief in the Night 1 Thes 5:2 Q/ Luke 12:39 Peace among yourselves 1 Thes Mark 9:50 Have peace with Everyone Romans 12:18 Mar 9:50 Do not judge Romans 13: 10 Q /Luke 6:37

Story by Kay Albright, (785) 864-8858

University Relations, the public relations office for the University of Kansas Lawrence campus. Copyright 1997

LAWRENCE - Fragments of a fourth-century Egyptian manuscript contain a lost gospel dating from the first or second century, according to Paul Mirecki, associate professor of religious studies at the University of Kansas.

Mirecki discovered the manuscript in the vast holdings of Berlin's Egyptian Museums in 1991. The book contains a rare "dialogue gospel" with conversations between Jesus and his disciples, shedding light on the origins of early Judaisms and Christianities.

The lost gospel, whose original title has not survived, has similarities to the Gospel of John and the most famous lost gospel, the gospel of Thomas, which was discovered in Egypt in 1945.

The newly discovered gospel is written in Coptic, the ancient Egyptian language using Greek letters. Mirecki said the gospel was probably the product of a Christian minority group called Gnostics, or "knowers."

Mirecki said the discussion between Jesus and his disciples probably takes place after the resurrection, since the text is in the same literary genre as other post-resurrection dialogues, though the condition of the manuscript makes the time element difficult to determine.

"This lost gospel presents us with more primary evidence that the origins of early Christianity were far more diverse than medieval church historians would tell us," Mirecki said. "Early orthodox histories denigrated and then banished from political memory the existence of these peaceful people and their sacred texts, of which this gospel is one."

Mirecki is editing the manuscript with Charles Hedrick, professor of religious studies at Southwest Missouri State University, Springfield. Both men independently studied the manuscript while working on similar projects in Berlin.

A chance encounter at a professional convention in 1995 in Philadelphia made both men realize that they were working on the same project. They decided to collaborate, and their book will be published this summer by Brill Publishers in the Netherlands.

The calfskin manuscript is damaged, and only 15 pages remain. Mirecki said it was probably the victim of an orthodox book burning in about the fifth century.

The 34 Gospels

Bible Review, June 2002: 20-31; 46-47

Charles W. Hendrick, professor who discovered the lost Gospel of the Savior tells us

Mirecki and I are not the first scholars to find a new ancient gospel. In fact scholars now have copies of 19 gospels (either complete, in fragments or in quotations), written in the first and second centuries A.D— nine of which were discovered in the 20th century. Two more are preserved, in part, in other andent writings, and we know the names of several others, but do not have copies of them. Clearly, Luke was not exaggerating when he wrote in his opening verse: "Many undertook to compile narratives [aboutJesus]" (Luke 1:1). Every one of these gospels was deemed true and sacred by at least some early Christians

These Gospels demonstrate a great diversity among the early chruch, the diminish the claims of an orthodox purity. On the other hand, they tell us more about the historical Jesus as well. One thing they all have in common is to that they show Jesus as a historical figure, working in public and conducting his teachings before people, not as a spirit being devoid of human life.Hendrick says,"Gospels-whether canonical or not- are collections of anecdotes from Jesus' public career."

Many of these lost Gospels pre date the canonical gospels, which puts them prior to AD 60 for Mark:

Hendrick:

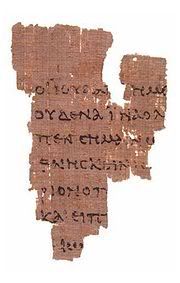

The Gospel of the Saviour, too. fits this description. Contrary' to popular opinion, Matthew, Mark, Luke and John were not included m the canon simply because they were the earliest gospels or because they were eyewitness accounts. Some non canonical gospels are dated roughly to the same period, and the canonical gospels and other early Christian accounts appear to rely on earlier reports. Thus, as far as the physical evidence is concerned, the canonical gospels do not take precedence over the noncanonical gospels. The fragments of John, Thomas and theEgerton Gospel share the distinction of being the earliest extant pieces of Christian writing known. And although the existing manuscript evidence for Thomas dates to the mid-second century, the scholars who first published the Greek fragments held open the possibility that it was actually composed in the first century, which would put it around the time John was composed.

The unknown Gospel of Papyrus Egerton 2

The unknown Gospel of Egerton 2 was discovered in Egypt in 1935 exiting in two different manuscripts. The original editors found that the handwriting was that of a type from the late first early second century. In 1946 Goro Mayeda published a dissertation which argues for the independence of the readings from the canonical tradition. This has been debated since then and continues to be debated. Recently John B. Daniels in his Clairmont Dissertation argued for the independence of the readings from canonical sources. (John B. Daniels, The Egerton Gospel: It's place in Early Christianity, Dissertation Clairmont: CA 1990). Daniels states "Egerton's Account of Jesus healing the leaper Plausibly represents a separate tradition which did not undergo Markan redaction...Compositional choices suggest that...[the author] did not make use of the Gospel of John in canonical form." (Daniels, abstract). The unknown Gospel of Egerton 2 is remarkable still further in that it mixes Johannie language with Synoptic contexts and vice versa. which, "permits the conjecture that the author knew all and everyone of the canonical Gospels." (Joachim Jeremias, Unknown Sayings, "An Unknown Gospel with Johannine Elements" in Hennecke-Schneemelcher-Wilson, NT Apocrypha 1.96). The Unknown Gospel preserves a tradition of Jesus healing the leper in Mark 1:40-44. (Note: The independent tradition in the Diatessaran was also of the healing of the leper). There is also a version of the statement about rendering unto Caesar. Space does not permit a detailed examination of the passages to really prove Koster's point here. But just to get a taste of the differences we are talking about:

| Egerton 2: "And behold a leper came to him and said "Master Jesus, wandering with lepers and eating with them in the inn, I therefore became a leper. If you will I shall be clean. Accordingly the Lord said to him "I will, be clean" and immediately the leprosy left him. | Mark 1:40: And the leper came to him and beseeching him said '[master?] if you will you can make me clean. And he stretched out his hands and touched him and said "I will be clean" and immediately the leprosy left him. |

| Egerton 2: "tell us is it permitted to give to Kings what pertains to their rule? Tell us, should we give it? But Jesus knowing their intentions got angry and said "why do you call me teacher with your mouth and do not what I say"? | Mark 12:13-15: Is it permitted to pay taxes to Caesar or not? Should we pay them or not? But knowing their hypocrisy he said to them "why do you put me to the test, show me the coin?" |

Koster:

"There are two solutions that are equally improbable. It is unlikely that the pericope in Egerton 2 is an independent older tradition. It is equally hard to imagine that anyone would have deliberately composed this apophthegma by selecting sentences from three different Gospel writings. There are no analogies to this kind of Gospel composition because this pericope is neither a harmony of parallels from different Gospels, nor is it a florogelium. If one wants to uphold the hypothesis of dependence upon written Gospels one would have to assume that the pericope was written form memory....What is decisive is that there is nothing in the pericope that reveals redactional features of any of the Gospels that parallels appear. The author of Papyrus Egerton 2 uses independent building blocks of sayings for the composition of this dialogue none of the blocks have been formed by the literary activity of any previous Gospel writer. If Papyrus Egerton 2 is not dependent upon the Fourth Gospel it is an important witness to an earlier stage of development of the dialogues of the fourth Gospel....(Koester , 3.2 p.215)

Gospel of Peter

Fragments of the Gospel of Peter were found in 1886 /87 in Akhimim, upper Egypt. These framents were from the 8th or 9th century. No other fragment was found for a long time until one turned up at Oxyrahynchus, which were written in 200 AD. Bishop Serapion of Antioch made the statement prior to 200 that a Gospel had been put forward in the name of Peter. This statement is preserved by Eusebius who places Serapion around 180. But the Akhimim fragment contains three periciopes. The Resurrection, to which the guards at the tomb are witnesses, the empty tomb, or which the women are witnesses, and an epiphany of Jesus appearing to Peter and the 12, which end the book abruptly.

Many features of the Gospel of Peter are clearly from secondary sources, that is reworked versions of the canonical story. These mainly consist of 1) exaggerated miracles; 2) anti-Jewish polemic.The cross follows Jesus out of the tomb, a voice from heaven says "did you preach the gospel to all?" The cross says "Yea." And Pilate is totally exonerated, the Jews are blamed for the crucifixion. (Koester, p.218). However, "there are other traces in the Gospel of Peter which demonstrate an old and independent tradition." The way the suffering of Jesus is described by the use of passages from the old Testament without quotation formulae is, in terms of the tradition, older than the explicit scriptural proof; it represents the oldest form of the passion of Jesus. (Philipp Vielhauer, Geschichte, 646] Jurgen Denker argues that the Gospel of Peter shares this tradition of OT quotation with the Canonicals but is not dependent upon them. (In Koester p.218) Koester writes, "John Dominic Crosson has gone further [than Denker]...he argues that this activity results in the composition of a literary document at a very early date i.e. in the middle of the First century CE" (Ibid). Said another way, the interpretation of Scripture as the formation of the passion narrative became an independent document, a ur-Gospel, as early as the middle of the first century!

Corosson's Cross Gospel is this material in the Gospel of Peter through which, with the canonicals and other non-canonical Gospels Crosson constructs a whole text. According to the theory, the earliest of all written passion narratives is given in this material, is used by Mark, Luke, Matthew, and by John, and also Peter. Peter becomes a very important 5th witness. Koester may not be as famous as Crosson but he is just as expert and just as liberal. He takes issue with Crosson on three counts:

So Helmutt Koester differs from Crosson mainly in that he divides the epiphanies up into different sources. Another major distinction between the two is that Crosson finds the story of Jesus burial to be an interpolation from Mark to John. Koester argues that there is no evidence to understand this story as dependent upon Mark. (Ibid). Unfortunately we don't' have space to go through all of the fascinating analysis which leads Koester to his conclusions. Essentially he is comparing the placement of the pericopes and the dependence of one source upon another. What he finds is mutual use made by the canonical and Peter of a an older source that all of the barrow from, but Peter does not come by that material through the canonical, it is independent of them.

1) no extant text,its all coming form a late copy of Peter,

2) it assumes the literary composition of latter Gospels can be understood to relate to the compositions of earlier ones; 3) Koester believes that the account ends with the empty tomb and has independent sources for the epihanal material.

Koester:

"A third problem regarding Crossan's hypotheses is related specifically to the formation of reports about Jesus' trial, suffering death, burial, and resurrection. The account of the passion of Jesus must have developed quite eary because it is one and the same account that was used by Mark (and subsequently Matthew and Luke) and John and as will be argued below by the Gospel of Peter. However except for the appearances of Jesus after his resurrection in the various gospels cannot derive from a single source, they are independent of one another. Each of the authors of the extant gospels and of their secondary endings drew these epiphany stories from their own particular tradition, not form a common source." (Koester, p. 220)

"Studies of the passion narrative have shown that all gospels were dependent upon one and the same basic account of the suffering, crucifixion, death and burial of Jesus. But this account ended with the discovery of the empty tomb. With respect to the stories of Jesus' appearances, each of the extant gospels of the canon used different traditions of epiphany stories which they appended to the one canon passion account. This also applies to the Gospel of Peter. There is no reason to assume that any of the epiphany stories at the end of the gospel derive from the same source on which the account of the passion is based."(Ibid)

Also see my essay Have Gaurds, Will Aruge in which Jurgen Denker and Raymond Brown also agree about the independent nature of GPete. Brown made his reputation proving the case, and publishes a huge chart in Death of the Messiah which shows the interdependent nature and traces it line for line. Unfortunately I can't reproduce the chart.

"The Gospel of Peter, as a whole, is not dependent upon any of the canonical gospels. It is a composition which is analogous to the Gospel of Mark and John. All three writings, independently of each other, use older passion narrative which is based upon an exegetical tradition that was still alive when these gospels were composed and to which the Gospel of Matthew also had access. All five gospels under consideration, Mark, John, and Peter, as well as Matthew and Luke, concluded their gospels with narratives of the appearances of Jesus on the basis of different epiphany stories that were told in different contexts. However, fragments of the epiphany story of Jesus being raised form the tomb, which the Gospel of Peter has preserved in its entirety, were employed in different literary contexts in the Gospels of Mark and Matthew." (Ibid, p. 240).

What all of this means is, that there were independent traditions of the same stories, the same documents, used by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John which were still alive and circulating even when these canonical gospels were written. They represent much older sources and the basic work which all of these others use, goes back to the middle of the first century. It definitely posited Jesus as a flesh and blood man, living in historical context with other humans, and dying on the cross in historical context with other humans, and raising from the dead in historical context, not in some ethereal realm or in outer space. He was not the airy fairy Gnostic redeemer of Doherty, but the living flesh and blood "Son of Man."

Moreover, since the breakdown of Ur gospel and epiphany sources (independent of each other) demands the logical necessity of still other sources, and since the other material described above amounts to the same thing, we can push the envelope even further and say that at the very latest there were independent gospel source circulating in the 40s, well within the life span of eye witnesses, which were based upon the assumption that Jesus was a flesh and blood man, that he had an historical existence. Note: all these "other Gospels" are not merely oriented around the same stories, events, or ideas, but basically they are oriented around the same sentences. There is very little actual new material in any of them, and no new stories. They all essentially assume the same sayings. There is some new material in Thomas, and others, but essentially they are all about the same things. Even the Gospel of Mary which creates a new setting, Mary discussing with the Apostles after Jesus has returned to heaven, but the words are basically patterned after the canonical gospels. It is as though there is an original repository of the words and events and all other versions follow that repository. This repository is most logically explained as the original events! Jesus actual teachings!

Koester and Crosson both agree that the PMR was circulating in written form with empty tomb and passion narrative, as early as 50AD

Canonical Gospels

The Diatessaon is an attempt at a Harmony of the four canonical Gospels. It was complied by Titian in about AD172, but it contains readings which imply that he used versions of the canonical gospels some of which contain pre markan elements.

In an article published in the Back of Helmut Koester's Ancient Christian Gospels, William L. Petersen states:

"Sometimes we stumble across readings which are arguably earlier than the present canonical text. One is Matthew 8:4 (and Parallels) where the canonical text runs "go show yourself to the priests and offer the gift which Moses commanded as a testimony to them" No fewer than 6 Diatessaronic witnesses...give the following (with minor variants) "Go show yourself to the priests and fulfill the law." With eastern and western support and no other known sources from which these Diatessaranic witnesses might have acquired the reading we must conclude that it is the reading of Tatian...The Diatessaronic reading is certainly more congielian to Judaic Christianity than than to the group which latter came to dominate the church and which edited its texts, Gentile Christians. We must hold open the possibility that the present canonical reading might be a revision of an earlier, stricter , more explicit and more Judeo-Christian text, here preserved only in the Diatessaron. (From "Titian's Diatessaron" by William L. Petersen, in Helmut Koester, Ancient Christian Gospels: Their History and Development, Philadelphia: Trinity Press International, 1990, p. 424)

The Jesus Narrative In Pauline Literature

Paul's allusions to the narrative relates to many points in the Gospels:

He was flesh and blood (Phil 2:6, 1 Tim 3:16) Born from the lineage of David (Rom 1:3-4, 2 Tim 2:8) Jesus' baptism is implied (Rom 10:9) The last supper (1 Cor 11:23ff) Confessed his Messiahship before Pilate (1 Tim 6:13) Died for peoples' sins (Rom 4:25, 1 Tim 2:6) He was killed (1 Cor 15:3, Phil 2:8) Buried (1 Cor 15:4) Empty tomb is implied (1 Cor 15:4) Jesus was raised from the dead (2 Tim 2:8)

Resurrected Jesus appeared to people (1 Cor 15:4ff) James, a former skeptics, witnessed this (1 Cor 15:7) as did Paul (1 Cor 15:8-9) This was reported at an early date (1 Cor 15:4-8) He asceded to heaven, glorified and exalted (1 Tim 3:16, Phil 2:6f) Disciples were transformed by this (1 Tim 3:16) Disciples made the Gospel center of preaching (1 Cor 15:1-4) Resurrection was chief validation of message (Rom 1:3-4, Rom 10:9-10) Called Son of God (Rom 1:3-4) Called Lord (Rom 1:4, Rom 10:9, Phil 2:11) Called God (Phil 2:6) Called Christ or Messiah (Rom 1:4, Phil 2:11

Summary and Conclusion

From this notion as a base line for the beginning of the process of redaction, and using the traditional dates given the final product of canonical gospels as the base line for the end of the process, we can see that it is quite probable that the canonical gospels were formed between 50 and 95 AD. It appears most likely that the early phase, from the events themselves that form the Gospel, to the circulation of a written narrative, there was a controlled oral tradition that had its hay day in the 30's-40's but probably overlapped into the 60's or 70's. The say sources began to be produced, probably in the 40's, as the first written attempt to remember Jesus' teachings. The production of a written narrative in 50, or there about, probably sparked interest among the communities of the faithful in producing their own narrative accounts; after all, they too had eye witnesses.

Between 50-70's those who gravitated toward Gnosticism began emphasizing those saying sources and narrative periscope that interested them for their seeming Gnostic elements, while the Orthodox honed their own orthodox sources that are reflected in Paul's choices of material,and latter in the canonical gospels themselves. So a great "divvying up" process began where by what would become Gnostic lore got it's start, and for that reason was weeded out of the orthodox pile of sayings and doings. By that I mean sayings Like "if you are near to the fire you are near to life" (Gospel of the Savior) or "cleave the stone and I am there" (Thomas) "If Heaven is in the clouds the birds of the air will get there before you" (Thomas) have a seeming gnostic flavor but could be construed as Orthodox. These were used by the Gnostically inclined and left by the Orthodox. That makes sense as we see the earliest battles with gnosticism beginner to heat up in the Pauline literature.

My own theory is that Mark was produced in several forms between 60-70, before finally comeing to rest in the form we know it today in 70. During that time Matthew and Luke each copied from different versions of it. John bears some commonality with Mark, according to Koester, becasue both draw upon the PMR. Thus the early formation of John began in 50-s or 60s, the great schism of the group probably happened in the 70's or 80s, with the gnostic bunching leaving for Egypt and producing their own Gnostic redaction of the gospel of John, the Orthodox group then producing the final form by adding the prologue which in effect, is the ultimate censor to those who left the group.

The Gospel material was circularizing throughout Church hsitory, form the infancy of the Church to the final production of Canonical Gospels. Thus the skeptical retort that "they weren't written until decades latter" is totally irrelevant. It is not the case,they were being written all along, and they were the product of the communities from which they sprang, the communities which originally witnessed the events and the ministry of Jesus Christ.