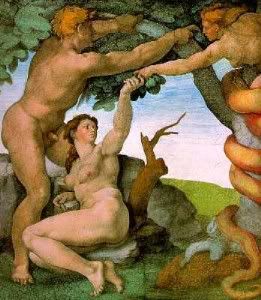

engraving on Assyrian cylinder represents tree of knowledge

The most radical view that I hold about the Bible, from the standpoint of evangelical Christians, is probably the idea that there are sections of the Bible that make use of Pagan mythology. This is a difficult concept for most Christians to grasp, because most of us are taught that "myth" means a lie, that it's a dirty word, an insult, and that it is really debunking the Bible or rejecting it as God's word. The problem is in our understanding of myth. "Myth" does not mean lie; it does not mean something that is necessarily untrue. It is a literary genre—a way of telling a story. In Genesis, for example, the creation story and the story of the Garden are mythological. They are based on Babylonian and Sumerian myths that contain the same elements and follow the same outlines. Those other stories are older so we know the Hebrew account must make use of them not vice verse. But three things must be noted: 1) Myth is not a dirty word, not a lie. Myth is a very healthy thing. 2) The point of the myth is the point the story is making--not the literal historical events of the story. So the point of mythologizing creation is not to transmit historical events but to make a point. We will look more closely at these two points. 3) I don't assume mythology in the Bible out of any tendency to doubt miracles or the supernatural, I believe in them. I base this purely on the way the text is written.

The purpose of myth is often assumed to be the attempt of unscientific or superstitious people to explain scientific facts of nature in an unscientific way. That is not the purpose of myth. A whole new discipline has developed over the past 60 years called "history of religions." Its two major figures are C.G. Jung and Marcea Eliade.[1] In addition to these two, another great scholarly figure arises in Carl Kerenyi.[2] These two form the basis, the foundation, for modern study of mythology. In addition to these three, the scholarly popularizer Joseph Campbell is important. Campell is best known for his work The Hero with A Thousand Faces.[3] This is a great book and I urge everyone to read it. Champbell, and Elliade both disliked Christianity intensely, but their views can be pressed into service for an understanding of the nature of myth. Myth is, according to Campbell a cultural transmission of symbols for the purpose of providing the members of the tribe with a sense of guidance through life. They are psychological, not explanatory of the physical world. This is easily seen in their elaborate natures. Why develop a whole story with so many elements when it will suffice as an explanation to say "we have fire because Prometheus stole it form the gods?" For example, Campell demonstrates in The Hero that heroic myths chart the journey of the individual through life. They are not explanatory, but clinical and healing. They prepare the individual for the journey of life; that's why in so many cultures we meet the same hero over and over again; because people have much the same experiences as they journey though life, gaining adulthood, talking their place in the group, marriage, children, old age and death. The hero goes out, he experiences adventures, he proves himself, he returns, and he prepares the next hero for his journey. We meet this over and over in mythology.[4]

In Kerenyi's essays on a Science of Mythology we find the two figures of the maiden and the Krone. These are standard figures repeated throughout myths of every culture. They serve different functions, but are symbolic of the same woman at different times in her life. The Krone is the enlightener, the guide, the old wise woman who guides the younger into maidenhood. In Genesis we find something different. Here the Pagan myths follow the same outline and contain many of the same characters (Adam and Adapa—see, Cornfeld Archaeology of the Bible 1976).[5] But in Genesis we find something different. The chaotic creation story of Babylon is ordered and the source of creation is different. Rather than being emerging out of Tiamot (chaos) we find "in the beginning God created the heavens and the earth." Order is imposed. We have a logical and orderly progression (as opposed to the Pagan primordial chaos). The seven days of creation represent perfection and it is another aspect of order, seven periods, the seventh being rest. Moreover, the point of the story changes. In the Babylonian myth the primordial chaos is the ages of creation, and there is no moral overtone, the story revolves around other things. This is a common element in mythology, a world in which the myths happen, mythological time and place. All of these elements taken together are called Myths, and every mythos has a cosmogony, an explanation of creation and being (I didn't say there were no explanations in myth.). We find these elements in the Genesis story, Cosmogony included. But, the point of the story becomes moral: it becomes a story about man rebelling against God, the entrance of sin into the world. So the Genesis account is a literary rendering of pagan myth, but it stands that myth on its head. It is saying God is the true source of creation and the true point is that life is about knowing God. The Bablylonian's had this creation story 1500 years before the Hebrews.[6] The actual story of the tree of knowledge and serpent tempting the woman is not found among the Babylonian writings. Yet we know that the story included these elements becuase we see those elements portrayed in art works of the era (see top).

Only a very small number of scholars think this way, however.[that there's no comparison] It is very clear that these stories share a common, ancient, way of speaking about the beginning of the cosmos. They participate in a similar “conceptual world” where solid barriers keep the waters away, pre-existent chaotic material exists before order, and light before the sun, moon, and stars.

Those similarities should not be exaggerated or minimized. But they are telling us something: even though Genesis is unique, and even though Genesis is Scripture, it is an ancient story that reflects ancient ways of thinking.

Genesis 1 cries out to be understood in its ancient context, not separated from it. Stories like Enuma Elish give us a brief but important glimpse at how ancient Near Eastern people thought of beginnings. As I discussed in an earlier post, ancient texts like Enuma Elish help us calibrate the genre of Genesis. That way we can learn to ask the questions Genesis 1 was written to address rather than intruding with our own questions.[7]

The mythological elements are more common in the early books of the Bible. The material becomes more historical as we go along. How do we know? Because the mythical elements of the first account immediately drop away. Elements such as the talking serpent, the timeless time ("in the beginning"), the firmament and other aspects of the myth all drop away. The firmament was the ancient world's notion of the world itself. It was a flat earth set upon angular pillars, with a dome over it. On the inside of the dome stars were stuck on, and it contained doors in the dome through which snow and rain could be forced through by the gods (that's why Genesis says "he divided the waters above the firmament from the waters below”). We are clearly in a mythological world in Genesis. The Great flood is mythology as well, as all nations have their flood myths. But as we move through the Bible things become more historical.

The NT is not mythological at all. The Resurrection of Christ is an historical event and can be argued as such (see Resurrection page). Christ is a flesh and blood historical person who can be validated as having existed. The resurrection is set in an historical setting, names, dates, places are all historically verifiable and many have been validated. So the major point I'm making is that God uses myth to communicate to humanity. The mythical elements create the sort of psychological healing and force of literary strength and guidance that any mythos conjures up. God is novelist, he inspires myth. That is to say, the inner experience model led the redactors to remake ancient myth with a divine message. But the Bible is not all mythology; in fact most of it is an historical record and has been largely validated as such.

The upshot of all of this is that there is no need to argue evolution or the great flood. Evolution is just a scientific understanding of the development of life. It doesn't contradict the true account because we don't have a "true" scientific account. In Genesis, God was not trying to write a science text book. We are not told how life developed after creation. That is a point of concern for science not theology.

How do we know the Bible is the Word of God? Not because it contains big amazing miracle prophecy fulfillments, not because it reveals scientific information which no one could know at the time of writing, but for the simplest of reasons. Because it does what religious literature should do, it is transformative.

No need for Halfway House

I have been in good discussions with evangelicals who knew their stuff and who intelligently argued that the ancestors of Abraham got the story of the creation form God and they kept it and the Pagans wrote it first, but the Hebrews kept it going orally and wrote it down latter. That may be possible but not likely. It's really dependent upon a lot of unlikely thing, such as an oral tradition that spans a thousand years with no written back up, then appeal to God to keep it going. It's not necessary to make that kind of gymnastic argument when we could just so much economically recognize that it's not meant to be a literal history. It does not have to be a literal history. Myth communicates with the psyche and that's the point of the story. That's why they use those pagan myths, becuase they communicate through he archetypes. Hebrew slaves in Babylon turned the story on its head. They probably combined it with their own Canaanite myths which were similar. Then they turned the story on its head saying "it's our God that was creator." That is not a lie and it's not a stretch becuase they are talking about the true creator. It is the case that in Hebrew religious genius they recognized the economy of one God and one reality behind it all.

[1] Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and The Profane: the Nature of Religion. New York: Harcourt, 1987, original English translation, 1959.

[2] Article on Carl Kerenyi in Wikipedia: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/K%C3%A1roly_Ker%C3%A9nyi accessed 8/28/13.

[3] Joseph Campbell, The Hero With A Thousand Faces: the Collected Works of Joseph Campbell. New World Library, third edition, 2008. Original publication was 1949.

[4] ibid. 1.

[5] Gaalyah Cornfeld, Archaeology of the Bible: Book by Book. New York: Harpercollins; 1st pbk. ed edition (May 1982) (originally 1976).

[6] "Chaldean Account of Genesis: Chapter V Babylonian Legend of Creation." Wisdom Library on line resource. http://www.wisdomlib.org/mesopotamian/book/the-chaldean-account-of-genesis/d/doc2817.html accessed 8/28/13.

[7]Pete Enns, "Genesis 1 and Babylonian Creation Story." The Biologos Forum: Science and Faith in Dialogue. blog: http://biologos.org/blog/genesis-1-and-a-babylonian-creation-story accessed 8/28/13.

Pete Enns is a former Senior Fellow of Biblical Studies for The BioLogos Foundation and author of several books and commentaries, including the popular Inspiration and Incarnation: Evangelicals and the Problem of the Old Testament, which looks at three questions raised by biblical scholars that seem to threaten traditional views of Scripture.