As I watched tv late the other night I saw one of those Christian stations where they show scenes of nature and play chruch music and you just sit there memorized by the beauty. Then they had a commentary by a guy I like named Paul Williams (not the short blond pudgy song writer of the 70s). This would be the worship network's own Paul Williams. About the only Christian Television I watch, those 'creation spaces.' Williams is about the only Christian talking head I like listening to on Christian tv. He had a little thing about the beauty of nature point beyond themselves to some greater reality because he feels there must be "someone to thank for it all." This reminded me of a God argument on my list I rarely use, no. 9 "argument from the sublime." My argument is a lot more sophisticated than Williams little one liner, but basically hints at the same idea. I was also reminded it of it's corollary and wondered if I could answer it. The corollary: The ugly evil horrible things in nature must also point beyond themselves. Do we also have God to thank for the bad things? If so how do we square that with Christian theology, and if not, why not? The myth of the fall? That opens another can of worms, in the from of "why wold God allow he fall." These are of course perinial questions I've known them all my life, I don't imagine I've solved them and I'm sure they will be around as long as humanity is around.

The other Paul Williams

The answer that I would tentatively take to the question of the fall must be understood against the background of my argument from sublime. It's ot argument from beauty per se but form the sublime which is somewhat different. The sublime can be either beautiful or terrible, horrible, ugly, monsters, catastrophic. Sublime does not mean "good." It means something beyond, far beyond our understanding or our limits. In the sense of the "terrible sublime" 9/11 was sublime. The Holocaust was sublime. These things totally transcend our limits, our capacity to understand and the framework we keep for the real. The good and the beautiful can surely be sublime as well. the Sunset is the beautiful sublime, Mother Teresa is the good sublime. To that extent the sublime itself sort of answers the issue of can we infer from evil that we have one to thank for that too? Of course there is always the answer that yes we do have one to blame for evil but it's not God. On the other hand since this will lead to the issue "isn't God more powerful why couldn't he stop satan," then we can't really just stop there. We need a transcendent overall answer that incorporates the whole.

The answer is, tentatively, that the sublime, being either beautiful or terrible points to a reality beyond the natural, the mundane. It points to a meaning beyond the world and beyond itself, beyond the things that make up the sublime of the moment. We get a sense of the overall profound nature of being and the ground and depth of being. We don't necessarily have a theological answer all wrapped up and ready to go but we can infer one. The sublime is not in itself a fall but evil is. That is to say, evil can surely be sublime, such as the Holocaust, but the evil aspects are not the same kind of thing that the good aspects of subliminal are, they are a fall from the good. How do we know they are a fall? Consider the creative and giving nature of being, love, the good. These are aspects that go together. Goodness is creative it's building it's not destructive, healing is not destroying. There's a sense in which destroying is part of work of healing and building, but in that sense it's not the evil aspects of destruction. The evil aspect is it's pointless non creative part of destruction, such as the Holocaust or 9/11.

Being, in itself the basic thing that it is to be is not to cease being not to destroy or take away but a positive force of being there, a standing firm a sense of giving. Being creates more being. Weather biological organizers, viruses, germs, evolution all the basic forces that enable prolongation of life are also creative of life. Being is giving out and leads to more being. Evil is a falling away from this standpoint of being there and healing and building and giving. Evil is a pointless taking away, destruction. Thus evil is a departure form the original, a falling away from the basic footing of the good or of being. Evil moves toward non being. Evil destructive, it creates no being, it is moving toward a loss of being. Thus the evil aspects have an element that is more than just the terrible sublime but also the pointless falling away form the sublime. That means we resisting tagging God with the responsibility for evil. Evil is moving in a direction away form God and from what God is and God does. Evil is a falling away.

St. Augustine said evil is the absence of the good. Evil is not a valid thing or a positive force is the absence of something. Like atheism is the absence of a belief, evil is the absence of the good. It's a falling away. It's not something God does it's something moves away form God. It's the putting away of God's love and God's presence and being without God. Evil is the absence of God. Now I will present my argument form the sublime and then tie it all up at the end.

Argument from The Sublime.

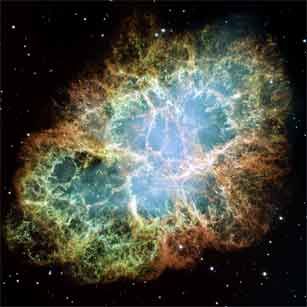

It always used to sound so stupid to me when people would say "O, look at the beautiful sun set, how can people deny that there's a God? (my Mother used to say that). Than after becoming a Christian I saw a really great sunset one day, the sky decked out in orange, pink, Gold, peach, cobalt, cerillian, and all punctuated by the most delicate suffering strips. It suddenly occurred to me why anyone would think that. Because we are the type of beings that are capable of appreciating beauty. It is not merely that aesthetic apprehension is beyond the ability of a dead random universe to produce, but that it spurs us to consider higher things. We realize from the appreciation of these things, art, music, poetry, literature, nature, that there is a realm of the sublime which transcends the mundane world of reductionism. I don't necessarily mean a supernatural realm--it could be a "realm" of our emergent qualities. But the fact that we can appreicate these things indicates that there is more to reality than merely the realm of science, technology, and the that to which reality is reduced by technocratic natrualists who can't appreciate higher possbilities.

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

"Sublime" refers to an aesthetic value in which the primary factor is the presence or suggestion of transcendent vastness or greatness, as of power, heroism, extent in space or time. It differs from greatness or grandeur in that these are as such capable of being completely grasped or measured. By contrast, the sublime, while in one aspect apprehended and grasped as a whole, is felt as transcending our normal standards of measurement or achievement. Two elements are emphasized in varying degree by different writers, and probably varying in different observers: (1) a certain baffling of our faculty with feeling of limitation akin to awe and veneration; (2) a stimulation of our abilities and elevation of the self in sympathy with its object.

That all people, given the right exposure, can appreciate the sublime, beauty in nature and art, in such a way as to seek some realm beyond that of the mudane physical is a direct implication that something more exists to be found. While this is not a proof of God in and of itself, it might be logica to infur from this sense of transcendence that reality is more than just the physical realm, and therefore, even though this is a highly subjective notion, if one finds that God satisfies this urge best of all, than God is probably the object of our longings for the sublime.

Peter Suber's Infinite Reflections

All college address at ST. John's College in Oct. 96

published St John's Review XLIV 2 (1998) 1-59

The Sublimity of the Infinite

"I am profoundly grateful that understanding infinity does not deprive it of its majesty. If the infinite were only interesting because of the paradoxes it generates, and the absorbing academic issues raised by the need to resolve them, then it would not be studied any more than self-reference, a prolific but more pedestrian engine of paradox. But the infinite is also majestic, one might say infinitely majestic."

"An hour under a clear sky at night, looking up, gives some sense of this. The depth of space is a wild blue yonder, not a true, perceived infinity.[Note 34] But it inspires contemplation of the true infinite, and the slightest brush with that idea is breath-taking, invigorating, expanding, lifting, calming, but also agitating, alluring, but also distant and magnificently indifferent. One reason to study mathematics is that you can get these feelings in broad daylight or indoors."

"There are many ways to become precise about these feelings, and many ways to praise and honor the infinite. I'd like to use Kant's term: it is sublime."[Note 35]

All college address at ST. John's College in Oct. 96

published St John's Review XLIV 2 (1998) 1-59

"Just for comparison, Cantor had a different set of numinous feelings about the infinite. He was not only a great mathematician, but a very religious man and by some standards a mystic. Yet his mysticism was supported by his mathematics, which to him was at least as strong an argument for the mathematics as for the mysticism.[Note 36] Apart from claiming divine inspiration for his work, we don't know exactly what spiritual views he linked to his mathematics, but his theorems[Note 37] give support to the following. Measured in meters, we are tiny specks compared to the universe at large. But measured in dimensionless points, we are as large as the universe: a proper subset, but one with the same cardinality as the whole. Similarly, measured in meters, we may be off in a corner of the universe. But measured in points, the distance is equally great in all directions, whether universe is finite or infinite; that puts us in the center, wherever we are. Measured in days, our lives are insignificant hiccups in the expanse of past and future time. But measured in points of time, our lives are as long as universe is old. We are as small as we seem, but simultaneously, by a most reasonable measure, co-extensive with the totality of being in both space and time. This is truly (as Blake put it) "[t]o see the world in a grain of sand and a heaven in a wild flower, hold infinity in the palm of your hand and eternity in an hour."[Note 38]

The first step is realizing we are the kind of beings who can appreciate the sublime. This appreiciation, though culturally bound, and though it is an aquired taste, stems form our basic nature as personally aware centers of consciousness. This is espeicially true in the way that art makes us think of transcendence. Why should the cold universe be able to produce centers of conscious awareness from dead matter? The structure for awareness must exist in the universe, and since the object of our awareness seems to be a longing for the sublime we can infurr that the answers lies in the sublime, in God.

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philsophy

James McCosh writting of Archibold Alison's theories

on the Sublime

"The conclusion, therefore, in which I wish to rest is, that the beauty and sublimity which is felt in the various appearances of matter are finally to be ascribed to their expression of mind; or to their being, either directly or indirectly, the signs of those qualities of mind, which are fitted, by the constitution of our nature, to affect us with pleasing or interesting emotion." There is a singular mixture of truth and error in this statement: truth, in tracing all beauty and sublimity to the expression of mind; but error, in placing it in qualities which raise emotion according to our constitution. Beauty, and sublimity are not the same as the true and the good; but they are the expression and the signs of the true and the good, suggested by the objects that evidently participate in them." {316}

If there is a higher reality there must be something real about it. To transcend the world is to obtain something of some higher realm. But an empty higher realm is meaningless. Since we are the kind of beings who can percieve the trasncendent we must have been created in such as way that we are capable of understanding the transcendent. If beauty is a sign of the good than the sublime must be a sign of the source of the good. Since we are personally conscious beings capable of reading the transcendent in a sunset we must have been created by a conscious being who is cabable of putting it there.

All The basic objections deal with reducing the phenominon to some naturalistic explaination and naturalizing it.

The skeptic might argue that the sublime is merely the resut of feeling overwhealed by the huge or awed by the beautiful and is therefore merely a stemulous response.

Internet Encyclopedia of Philsophy

http://www.utm.edu/research/iep/s/sublime.htm

"The element of magnitude in beauty was noted by Aristotle, and given by him a prominent place in tragedy. But the earliest extant determination of the sublime as a distinct conception is in the treatise ascribed to Longinus, but now supposed to be of earlier date (first century C.E.). In modern philosophy, it was given special prominence by Edmund Burke in his Essay on the Sublime and Beautiful (1756) and Henry Home in his Elements of Criticism who sought a psychological and physiological explanation. According to Burke, it is caused by a "mode of terror or pain," and is contrasted with the beautiful (rather than being part of the beautiful). Kant also distinguished it as a separate category form beauty, making it apply properly only to the mind, not to the object, and giving it a peculiar moral effect in opposing "the interests of sense." He distinguished a mathematical sublime of extension in space or time, and a dynamic of power. Most subsequent writers on aesthetics tend to bring the sublime within the beautiful in the broader sense insofar as its aesthetic quality is closely related to that of beauty."

Suber:

"As long as we are physically safe when viewing the sublime immensity, Kant argues, it helps us know our moral dignity and nonphysical invulnerability undiminished, even accentuated, by our forceful acknowledgment of our physical smallness and frailty."[Note 42]

Clearlythe sublime is not reducible to just fear, terror, or beauty. If so, why would these three (really two) very different things bring on the same response? And again this is missing the mark. The real question is why are we the sort of beings who can experience this sense? Animals in nature navigate to a large extent by pattern recognition. We should not be surprised to find that we did evolve a sense of the sublime, we are after all physical creates and we evolved. On the other hand why would be evolve such a highhanded sense of it? And moreover, since it is not reducible to any one of these things, but may be triggered by them (as well as by mathematics and abstractions) than it is transcendent in itself beyond any of these reductionist accounts.

Of course the reductionists will tell us that beauty and aesthetics began as some form of communication, it helped us determine who to mate with and how to avoid posion berries or something. To take that line is merely silly. It simpley reduces these things to less than they are. If we catch a glipse of the sublime we do understand that "something is afoot in the universe" (uh, Godwise).

The Recognition of certain states of being, or tensions produced by being dwarfed in immensity bring on the sublime.

Peter Suber's Infinite Reflections

All college address at ST. John's College in Oct. 96

published St John's Review XLIV 2 (1998) 1-59

"Kant's theory of the sublime does not rest on these Cantorian theorems. His chief thesis for our purposes is that, "That is sublime in comparison with which everything else is small."[Note 39] Clearly the infinitely large is a perfect fit for this definition.[Note 40]

"The sublime is not an easy notion, and the best approach to it may be via negativa, showing how it differs from something familiar, the beautiful. Sticking only to those differences which bear most on the sublimity of the infinite, Kant says that the beautiful concerns a bounded object while the sublime object can be unbounded; the beautiful is compatible with charms while the sublime is not; the beautiful attracts the mind while the sublime both attracts and repels it; and the beautiful "seems as it were predetermined for our power of judgment" while the sublime is "incommensurate with our power of exhibition, and as it were violent to our imagination, and yet we judge it all the more sublime for that."[Note 41]

"The infinitely large meets these criteria almost by design. The infinitely large is unbounded, incommensurate with our powers of imagination, and to engage and satisfy us it no more needs charm than spring water needs sugar. It is so large that some of its proper subsets are just as large, a property shared by no finite magnitude."

"What triggers the feeling of the sublime most is immensity. Immensity in turn makes us feel a tension between two aspects of ourselves. On the one hand it makes us feel the inadequacy of our senses and imagination. On the other it makes us feel that there is more to us than senses and imagination, whose adequacy cannot be brought into question by immensity, no matter how spectacular or infinite. This second dimension of ourselves is not conception but moral vocation. While physically the immensity dwarfs us into insignificance, this very fact highlights that within us which is not dwarfed.

The Internet Encyclopedia of Philsophy James McCosh writting of Archibold Alison's theories

on the Sublime

"But there is a higher element than all this in beauty; an element seen by Plato and by those who have so far caught his spirit,-- such as, Augustine, Cousin, MacVicar, and Ruskin, but commonly overlooked by men of science and the upholders {315} of the association theory. The mere sensations or perceptions called forth by the presence of harmonious sounds, colors, and proportional forms, is not the main ingredient in the lovely and the grand. Beauty, after all, lies essentially in the ideas evoked. I hold by an association theory on this subject. But the ideas entitled to be called aesthetic should be of mind, and the higher forms of mind, intellectual and moral. There was, therefore, grand truth in the speculation of Plato, that beauty consists in the bounding of the waste, in the formation of order out of chaos; or, in other words, in harmony and proportion. There was truth in the theory of Augustine, that beauty consists ill order and design; and in that of Hutcheson, that it consists in unity with variety. Alison had, at times, a glimpse of this truth, but then lost sight of it. He speaks with favor of the doctrine held by Reid, that matter is not beautiful in itself, but derives its beauty from the expression of mind; he holds it true, so far as the qualities of matter are immediate signs of the powers or capacities of mind, and in so far as they are signs of those affections or dispositions of mind which we love, or with which we are formed to sympathize. He thus sums up his views: "

b) Therefore, not reduceable to patterns.

"The idea in the pattern recognition argument is that patterns that trigger the sense of the sublime key us in to the feelings of fear or beauty that we have experinced in the past and almost hypnotically cerate the sense of awe. Nevertheless the concept is comlpex and cannot be reduced to merely a sring of patterns. This argument makes sense in thinking of music or visual effects, but form the sense of aloneness in nature or the night sky we are reaction to more than juat pattern recognition. IT can also affect us with new pattterns or with non -physical phenomena such as mathematics."

3) Chemical determinism.

a) Functionalist can't make good on their claims.

The brain/mind reductionists that try to say that consciousness is nothing more than chemicals in the brain (brain function) are simpley missing the point. Here is a long (I mean really long long long) boring dry but excellently scientific article showing that these guys are no where near figuring out what consciousness is, and that the complexity of the brain is still so vast we can look in wonderment at the sunset and dream of trasncendent possibilities, and commune with nature and sense God's reality without fear that we are nothing more than an accidently produced batch of neurons chemicals. Lantz Miller (who is not a Christian and it not a religious article) The Hard Sell of Human Consciousness (part I).

(See also the answers below on Consciousness argument which draw upon Miller's work)

To reduce the sublime to mere chemical determinism or brian functionalism loses the phenomena. When we try to analyze or disect the sublime we lose the charictoristics that trigger it. These attempts merely ignore what is being experienced.

One of the major arguments is that we appreciate beauty as an evolutionary function so that we will seek out the better mates and have good genes. But this is super reductionism that ignores all kinds of phenomena. I do not get horny looking at sunset s or studying set theory, I do sense the sublime on those occassions. The sublime is a value added proposition and there is basically no reason for it in evolution.

More on Wednesday.