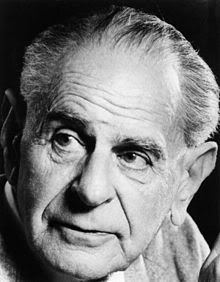

Karl Popper

footnote numbers taken over from part 1.

Not Facts but Verisimilitude:

Karl

Popper (1902-1994) is one of the most renewed and highly respected

figures in the philosophy of science. Popper was from Vienna, of Jewish

origin, maintained a youthful flirtation with Marxism, and left his

native land due to the rise of Nazism in the late thirties. He is

considered to be among the ranks of the greatest philosophers of the

twentieth century. Popper is highly respected by scientists in a way

that most philosophers of science are not.[15]

He

was also a social and political philosopher of considerable stature, a

self-professed ‘critical-rationalist’, a dedicated opponent of all

forms of scepticism, conventionalism, and relativism in science and in

human affairs generally, a committed advocate and staunch defender of

the ‘Open Society’, and an implacable critic of totalitarianism in all

of its forms. One of the many remarkable features of Popper's thought

is the scope of his intellectual influence. In the modern technological

and highly-specialised world scientists are rarely aware of the work

of philosophers; it is virtually unprecedented to find them queuing up,

as they have done in Popper's case, to testify to the enormously

practical beneficial impact which that philosophical work has had upon

their own. But notwithstanding the fact that he wrote on even the most

technical matters with consummate clarity, the scope of Popper's work

is such that it is commonplace by now to find that commentators tend to

deal with the epistemological, scientific and social elements of his

thought as if they were quite disparate and unconnected, and thus the

fundamental unity of his philosophical vision and method has to a large

degree been dissipated.[16]

Unfortunately

for our purposes we will only be able to skim the surface of Popper’s

thoughts on the most crucial aspect of this theory of science, that

science is not about proving things but about falsifying them.

Above

we see that Dawkins, Stenger and company place their faith in the

probability engineered by scientific facts. The problem is probability

is not the basis upon which one chooses one theory over another, at

least according to Popper. This insight forms the basis of this notion

that science can give us verisimilitude not “facts.” Popper never uses

the phrase “fortress of facts,” we could add that, science is not a

fortress of facts. Science is not giving us “truth,” its’ giving

something in place of truth, “verisimilitude.” The term verisimilar means “having the appearance of truth, or probable.” Or it can also mean “depicting realism” as in art or literature.”[17]

According to Popper in choosing between two theories one more probable

than the other, if one is interested I the informative content of the

theory, one should choose the less probable. This is paradoxical but

the reason is that probability and informative content very inversely.

The higher informative content of a theory is more predictive since the

more information contained in a statement the greater the number of

ways the statement will turn out to fail or be proved wrong. At that

rate mystical experience should be the most scientific view point. If

this dictum were applied to a choice between Stenger’s atheism and

belief in God mystical God belief would be more predictive and have

less likelihood of being wrong because it’s based upon not speaking

much about what one experiences as truth. We will see latter that this

is actually the case in terms of certain kinds of religious

experiences. I am not really suggesting that the two can be compared.

They are two different kinds of knowledge. Even though mystical

experience per se can be falsified (which will be seen in subsequent

chapters) belief in God over all can’t be. The real point is that

arguing that God is less probable is not a scientifically valid

approach.

Thus

the statements which are of special interest to the scientist are

those with a high informative content and (consequentially) a low

probability, which nevertheless come close to the truth. Informative

content, which is in inverse proportion to probability, is in direct

proportion to testability. Consequently the severity of the test to

which a theory can be subjected, and by means of which it is falsified

or corroborated, is all-important.[18]

Scientific

criticism of theories must be piecemeal. We can’t question every

aspect of a theory at once. For this reason one must accept a certain

amount of background knowledge. We can’t have absolute certainty.

Science is not about absolute certainty, thus rather than speak of

“truth” we speak of “verisimilitude.” No single observation can be

taken to falsify a theory. There is always the possibility that the

observation is mistaken, or that the assumed background knowledge is

faulty.[19]

Uneasy with speaking of “true” theories or ideas, or that a

corroborated theory is “true,” Popper asserted that a falsified theory

is known to be false. He was impressed by Tarski’s 1963 reformulation of

the corresponded theory of truth. That is when Popper reformulated his

way of speaking to frame the concept of “truth-likeness” or

“verisimilitude,” according to Thronton.[20]

I wont go into all the ramifications of verisimilitude, but Popper has

an extensive theory to cover the notion. Popper’s notions of

verisimilitude were critixized by thinkers in the 70’s such as Miller,

Tichy’(grave over the y) and Grunbaum (umlaut over the first u) brought

out problems with the concept. In an attempt to repair the theory

Popper backed off claims to being able to access the numerical levels

of verisimilitude between two theories.[21]

The resolution of this problem has not diminished the admiration for

Popper or his acceptance in the world of philosophy of science. Nor is

the solution settled in the direction of acceptance for the fortress of

facts. Science is not closer to the fact making business just because

there are problems with verisimilitude.

Science doesn’t prove but Falsifies

The aspect of Popper’s theory for which he is best known is probably the idea of falsification. In 1959 He published the Logic of Scientific Discovery in

which he rigorously and painstakingly demonstrated why science can’t

prove but can only disprove, or falsify. Popper begins by observing that

science uses inductive methods and thus is thought to be marked and

defined by this approach. By the use of the inductive approach science

moves from “particular statements,” such as the result of an experiment,

to universal statements such as an hypothesis or theories. Yet, Popper

observes, the fallacy of this kind of reasoning has always been known.

Regardless of how many times we observe white swans “this does not

justify the conclusion that all swans are white.”[22]

He points out this is the problem of universal statements, which can’t

be grounded in experience because experience is not universal, at

least not human experience. One might observe this is also a problem of

empirical observation. Some argue that we can know universal

statements to be true by experience; this is only true if the

experiences are universal as well. Such experience can only be a

singular statement. This puts it in the same category with the original

problem so it can’t do any better.[23]

The only way to resolve the problem of induction, Popper argues, is to

establish a principle of induction. Such a principle would be a

statement by which we could put inductive inferences into logically

acceptable form. He tells us that upholders of the need for such a

principle would say that without science can’t provide truth or

falsehood of its theories.[24]

The

principle can’t be a purely logical statement such as tautology or a

prori reasoning, if it could there would be no problem of induction.

This means it must be a synthetic statement, empirically derived. Then he asked “how can we justify statement on rational grounds?” [25]

After all he’s just demonstrated that an empirical statement can’t be

the basis of a universal principle. Then to conclude that there must be

a universal principle of logic that justifies induction knowing that

it ahs to be an empirical statement, just opens up the problem again.

He points out that Reichenbach[26] would point that such the principle of induction is accepted by all of science.[27] Against Reinchenback he sties Hume.[28] Popper glosses over Kant’s attempt at a prori justification of syetnic a priori statements.[29]

In the end Popper disparages finding a solution and determines that

induction is not the hallmark of science. Popper argues that truth

alludes science since it’s only real ability is to produce probability.

Probability and not truth is what science can produce. “…but scientific

statements can only attain continuous degrees of probability whose

unattainable upper and lower limits are truth and falsity’.”[30] He goes on to argue against probability as a measure of inductive logic.[31]

Then he’s going to argue for an approach he calls “deductive method of

testing.. In this case he argues that an hypothesis can only be

empirically tested and only after it has been advanced. [32]

What

has been established so far is enough to destroy the fortress of facts

of idea. The defeat of a principle of induction as a means of

understanding truth is primary defeat for the idea that science is going

about establishing a big pile of facts. What

all of this is driving at of course is the idea that science is not so

much the process of fact discovery as it is the process of elimination

of bad idea taken as fact. Science doesn’t prove facts it disproves

hypotheses.. Falsifying theories is the real business of science. It’s

the comparison to theory in terms of what is left after falsification

has been done that makes for a seeming ‘truth-likeness,’ or

verisimilitude. Falsification is a branch of what Popper calls

“Demarcation.” This issue refers to the domain or the territory of the

scientists work. Induction does not mark out the proper demarcation. The

criticism he is answering in discussing demarcation is that removing

induction removes for science it’s most important distinction from

metaphysical speculation. He states that this is precisely his reason

for rejecting induction because “it does not provide a suitable

distinguishing mark of the empirical non metaphysical character of a

theoretical system,”[33] this is what he calls “demarcation.”

Popper

writes with reference to positivistic philosophers as the sort of

umpires of scientific mythology. He was a philosopher and the project of

the positivists was to “clear away the clutter” (in the words of A.J.

Ayer) for science so it could get on with it’s work. Positivistic

philosophers were the janitors of science. Positivists had developed the

credo that “meaningful statements” (statements of empirical science)

must be statements that are “fully decided.” That is to say, they had to

be both falsifiable and verifiable. The

requirement for verifiable is really a requirement similar to the

notion of proving facts, or truth. Verifiability is not the same thing

as facticiy or proof it’s easy to see how psychologically it reinforces

th sense that science is about proving things. He quotes several

positivists in reinforcing this idea: Thus Schlick says: “. . . a

genuine statement must be capable of conclusive verification” Waismann

says, “If there is no possible way to determine whether a statement is

true then that statement has no meaning whatsoever. For the meaning of a

statement is the method of its verification.”[34]

Yet Popper disagrees with them. He writes that there is no such thing

as induction. He discusses particular statements which are verified by

experience just opens up the same issues he launched in the beginning

one cannot derive universal statements from experience. “Therefore,

theories are never theories are never empirically verifiable. He argues

that the only way to deal with the demarcation problem is to admit

statements that are not empirically verified.[35]

But I shall certainly admit a system as empirical or scientific only if it

is capable of being tested by experience. These considerations suggest

that not the verifiability but the falsifiability of a system is to be taken as a

criterion of demarcation. In other words: I shall not require of a

Scientific system that it shall be capable of being singled out, once and

for all, in a positive sense; but I shall require that its logical form shall

be such that it can be singled out, by means of empirical tests, in a

negative sense: it must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience.[36]

What

this means in relation to the “fortress of facts” idea is that it

transgresses upon the domain of science. Compiling a fortress of facts

is beyond the scope of science and also denudes science of it’s domain.

He

deals with the objection that science is supposed to give us positive

knowledge and to reduce it to a system of falsification only negates

its major purpose. He deals with this by saying this criticism carries

little weight since the amount of positive information is greater the

more likely it is to clash. The reason being laws of nature get more

done the more they act as a limit on possibility, in other words, he

puts it, “not for nothing do we call the laws of nature laws. They more

they prohibit the more they say.”[37]

[15] Steven Thornton, “Karl Popper,” The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Winter 2011 edition Edward N. Zalta Editor, URL: http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2011/entries/popper/ vested 2/6/2012

[16] ibid

[17] Miriam-Webster. M-W.com On line version of Webster’s dictionary. URL: http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/verisimilar?show=0&t=1328626983 visited 2/7/2012

[18] Thornton, ibid.

[19] ibid

[20] ibid

[21] ibid

[22]

Karl Popper, The Logic of Scientific Discovery. London, New

York:Routledge Classics, original English publication 1959 by Hutchison

and co. by Routldege 1992. On line copy URL: http://www.cosmopolitanuniversity.ac/library/LogicofScientificDiscoveryPopper1959.pdf digital copy by Cosmo oedu visited 2/6/2012, p4

[23] ibid

[24] ibid

[25] ibid, 5

[26] Hans

Reinchenbach (1891-1953) German philosopher, attended Einstein’s

lectures and contributed to work on Quantum Mechanics. He fled Germany to escape Hitler wound up teaching at UCLA.

[27] Popper, ibid, referece to , H. Reichenbach, Erkenntnis 1, 1930, p. 186 (cf. also pp. 64 f.). Cf. the penultimate paragraph of Russell’s chapter xii, on Hume, in his History of Western Philosophy, 1946,

p. 699.

[28] ibid, Popper, 5

[29] ibid, 6

[30] ibid 6

[31] ibid, 7

[32] ibid

[33] ibid 11

[34] ibid, 17, references to Schlick, Naturwissenschaften 19, 1931, p. 150. and Waismann, Erkenntnis 1, 1903, p. 229.

[35] Ibid 18

[36] ibid

[37] ibid, 19 the quotation about laws is found on p 19 but the over all argument is developed over sections 31-46 spanning pages 95-133.

No comments:

Post a Comment