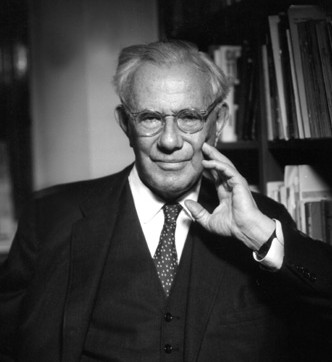

Paul Tillich 1886-1965

In this essay, which is a chapter from the new book I'm now working on, I'm moving toward defining what I think Tillich means exactly by being itself. It's a long journey but an important one.What does Tillich actually mean by “being itself?” Does he mean the same things as other theologians who use the phrase? It’s a mysterious sounding phrase and Tillich never actually comes out and says what he means by it. As I will show there is a reason for this, and I will show what I think that reason in is. In the mean time the task of this chapter is to deduce exactly what Tillich actually means by this phrase. There are three basic possibilities:

Three alternatives as to meaning

(1) The basic fact that things exist is all that the concept of “God” amounts to.

(2) There is a special quality to being, an impersonal aspect” ground of being” or “being itself” and that quality constitutes ‘the divine.’ This possibility excludes God as “king of the universe.”

(3) God is beyond our understanding, we can’t explain God but God is on a higher metaphysical level, and is not a thing to be classed with other things in creation; God is foundational to creation and to all things; God is “on the order of being itself; this might include but is not limited to a consciousness, or something like a Platonic form.

The first alternative can be ruled out immediately. If this were the case it would make Tillich an out and out atheist, with no belief in “God” to any real extent, and a very cynical atheist (more so than most) because he would be an atheist who can’t openly own up to his atheism. This is not really realistic possibility and this becomes clear as one reads Tillich. He’s clearly talking about something that is real and that is distinguished form just the mere fact that things exist. In fact he ruled this out himself in speaking of being “having depth” and excluding the possibility of atheism on the grounds that “being has depth” and that if one is aware of this one cannot be an atheist.

The name of infinite and inexhaustible depth and ground of our being is God. That depth is what the word God means. And if that word has not much meaning for you, translate it, and speak of the depths of your life, of the source of your being, of your ultimate concern, of what you take seriously without any reservation. Perhaps, in order to do so, you must forget everything traditional that you have learned about God, perhaps even that word itself. For if you know that God means depth, you know much about Him. You cannot then call yourself an atheist or unbeliever. For you cannot think or say: Life has no depth! Life itself is shallow. Being itself is surface only. If you could say this in complete seriousness, you would be an atheist; but otherwise you are not.[1]

This one quote is very important because it gives us several clues as to the meaning of the phrase as well as how to understand the reality of God as the Ground of Being. We will come back to this phrase. For the moment the important point to realize is that since he distinguishes between being as having depth, and “surface level of things” presumably the mere fact of existence, it seems clear he’s saying God is more than just the fact that things exist. This still doesn’t let him off the hook, however, in the eyes of some theological groups because it does not allay the Evangelical fears that what he really means is still un impersonal source of life rather than a God with a will and plan for your life. I will argue eventually that he does mean a God with will and a plan for your life, although the “plan” may not be as overt as we would like, the will may be harder to discern than we would like.

The second alternative, a special aspect of being, is no doubt part of what he means. I set up the second alternative to raise the issue raised by one of my former professors from Perkins school of Theology (SMU) that Tillich is merely reducing God below the level of the cognitive will to avoid coping with the moral aspects of God’s commands. [2] The issue of consciousness and personhood of God will be discussed in a subsequent chapter, and must be bracketed for the moment. On the other hand, to the extent that third alternative implies a stronger connection to the personal or the conscious than does the first I must tip my hand already and say that I will argue for the third alternative. Tillich does say that God is not “a person” (because he’s not a thing among other things in creation—not a contingency) but is “the personal itself.” This implies that God does contain an aspect of the conscious in some sense, specifically the structure that gives rise to consciousness as a whole. He speaks of being’s self affirmation.[3] This might lead us to think that he really did hold out of a “personal God,” and yet what is the “personal itself?” We are back at square one wondering what this “itself” thing is about. If the third alternative is not what Tillich had in mind, which I argue it is, it is what I have in mind anyway. Nevertheless, one clue we have is the distinction between possibility 2 and possibility 3, and what Tillich is doing with the concept of God in speaking this way. There is a more important distinction between option 2 and 3 than just the personal dimension; that of the distinction between God as just an aspect of being alongside other aspects, vs God as the basis of all reality, which the term “ground of being” might imply. The issue here is independent of the personal dimension, but no less important. The major point that Tillich is trying to make in speaking of God as “being itself” rather than “as aspect of being” is that God is not just another part of being; God is the basis of all being. The way of approaching the topic and the way speaking about God is Tillich’s attempt to guard the mystery of God without trying to explain things that are beyond our understanding, while communicating enough to tease one into seeking deeper realization.

We can see this method at work in the way Tillich writes about other great Christian theologians. One such example is his take on Luther. Luther was one of his heroes, he was Lutheran, so it’s only natural that he would seek to spot one of his pet issues in Luther’s work. I am sure that he’s reading it in, or rather, I am prepared to find that he’s reading it in. If one were to argue “he’s only reading his own hobby horse into Luther,” I would be content to go along with that take. On the other hand, there must be element of this view in Luther that allow him to read it in (if that’s what he’s doing) and more importantly, it does show us what Tillich believed, whether or not it shows us what Luther thought. Tillich believed that Luther had one of the most profound conceptions of God in human history. [4] Tillich quotes Luther:

Luther Denies everything which could make God finite, or a being beside others. ‘Nothing is so small, God is even smaller. Nothing is so Large God is even larger.’ ‘He is an unspeakable being, above and outside everything we can name and think. Who knows what this is, which is called-- God?’ ‘It is beyond body, beyond spirit, beyond everything we can see, hear and think.’ He makes the great statement that God is nearer to all creatures then they are to themselves. Tillich quotes Luther:

‘God has found a way that his own divine essence can be completely in all creatures, and in everyone especially, deeper, more internally, more present than the creature is to itself an at the same time and at the same time no where and can’t be comprehended by anyone so that he embraces all things and is within them. God is at the same time in every piece of sand totally, and nevertheless in all above all and out of all creatures.’Tillich continues:

In these formulae the only conflict between theistic and pantheistic tendencies is solved; they show the greatness of God, the inescapability of his presence, and at the same time his absolute transcendence. I would say very dogmatically that any doctrine of God that leaves out one of these elements does not really speak of God but of something less than God.[5] (emphasis mine).

This is a very important concept and the key to the whole issue of understanding the notion of God as being itself; that is this idea that God is not a being alongside other beings in the universe, or in creation. God is the basis of all being. In fact Tillich does not speak of God as “a being” he leaves out the “a” but simply says that God is “being itself” not “a being itself.”

Leaving out the “a” is essential to understanding the concept. This is essential because the whole concept turns upon the idea that God is above the level things, above contingency, in a category by itself. True to the mystical concept Tillich understands that God is beyond our comprehension. God blows away all of our easy preconceived categories that we have taken for granted since we first learned to talk. Yet though God is beyond everything we name, think, or understand, he is beyond these things in a metaphysical sense; yet “God does not sit beside the world looking at it from outside but he is acting in everything in every moment.”[6] Tillich understands omnipotence not as talk about what God can and cannot do but as “creative power.” It’s this sense of God as a dynamic reality working actively in concert with the natural world that endears him to the process theologians. [7]

Of course none of this will satisfy the “new atheist” fundamentalists. The atheist fundies want only hard facts. This is all a phantasmagoria of made up crap. But, to get to the point where we can talk about the “facts” we have to be certain of what we are talking about. It’s very important to understand the concepts clearly. Some of the atheists with whom I have tried to discuss these things for years, still do not get the “not a being” aspect of it. Because they don’t understand this their arguments never apply. They are constantly arguing “there can be no such thing as a necessary being.” But their argument applies to a big man in the sky, a localized individual being who is like others, one of many, and who functions in a very similar way to biological humanity. They can’t for the life of them seem to understand the concept that eternal necessary being doesn’t mean “an eternal necessary being” but “being itself” the thing that being is, the begin ness of being so to speak, rather an individual being. Dawkins argument that God is improbable (The God Delusion) is based upon these same assumptions. Thus the argument he makes would not apply to any Christians view because it assumes God is a big biological organism, but it applies even less to Tillich’s view because it assumed on top of that that God is an individual manifestation of being and thus subject to being. Anything using the indefinite article assumes one of many. A penny assumes there is more than one penny, and this particular penny is an example of the many pennies that there are. A being is one of many, it is an example of one of the many beings that there are. But God is not a single individual being. That doesn’t mean there’s more than one God, it means that God transcends the easily understood category that we take for granted. In New Testament God is “The God” (‘0 Theos). This is a way of speaking of the quality of divinity itself. Literally John 1: 1 says “The God.” “The word was with the God.” One could translate the word was with deity, or as “the word was divine.”

This is the sort of reason for which Tillich loses the “a” in “being.” God is not one of many but is on a higher level and belongs to a higher class. God is not a product of being. God is not subject to being, conversely God cannot cease being. This is part of what Tillich means by “depth.” If we know being has depth we can’t be atheists. Why would that be? Because the situation in regard to being is not what it seems on the surface? The easily taken for granted situation that appears on the surface is not what is, and what is, is not what seems to be. We look at the surface we assume things exist, all that exists must be tangible and must be one of the many things in the world, the huge list of ships and strings and sealing wax, cabbages and kings; yet God does not belong on the list. God is not one of these things but is the basis of these things.

God is the foundation of their existence, the basis upon which they are allowed to cohere; the ground of their being. Thus God is above the list. The divine cannot be represented with the indefinite article because there can only be one ground of being. There can’t be a pantheon, they would all cancel each other out; which one is the ground of the other’s being? If there is one being in all of existence, then that one being is the ground of all being. If there is not one they all cancel each other out because they are all the ground of being then there is no ground of being. One could argue “its existence by a committee” but what’s the ground of the committee? If each member of the committee is “a being” then how can the committee itself be “the ground of being?”

Atheists pondering that will probably think in terms of a committee of very powerful beings could so make all the objects in the universe and thus be the creators of the universe. Sure they could but that’s not really the point. That would just be moving problem back one stage because you have to ask “what is the ground of being for this committee. It’s an eternal committee of individual’s beings that are not the ground of being but as a committee they are the ground of being? The problematic nature here is obvious. It’s much more elegant to propose a single ground of all being that is eternal, necessary, self sustaining and that transcends any particular list of articles in the universe by virtue of the fact that it is the maker of list. This is an example of what Tillich means by this enigmatic phrase “if you know being has depth you can’t be an atheist.” But of course to move to the point where it’s more than just a concept we need to say more. What does Tillich really mean by the phrase “ground of being,” what does that tell us about the nature of God? Tillich is fond of saying that God is the power of being.

God – power of being

Tillich speaks of God as the “Power of being,” and in his Systematic Theology (vol. II) He groups this phrase with ground of being and being itself as epithets of the divine. In volume II he explains what he means by the power of being and he does so in the context of answering an argument leveled at this concept by the nominalists. This is an example of what has been said above about Tillich’s concern for the philosophical controversies of the middle ages; the period was still living in Tillich’s mind. Yet this is not merely an example of a musty out of date thinker raking up ideas form the past no one understands or holds to, or reliving battles of the past long forgotten. When we read the term “nominalistis” in his writings we should read “modern scientific reductionists” as well as from Tillich’s time “postivisits.” The analogy is perfect and it was very real for Tillich. The same criticism made by the nominalists is made by modern reductionsits and scientism buffs. This very argument that Tillich answers in his Systematic Theology volume II has been made against my discussion of God as being itself by modern reductionistic atheists on the internet. This is a very long passage but it is well worth reading because it speaks volumes. Note in this passage the link between ground of being and power of being:

When a doctrine of God is initiated by defining God as being itself, the philosophical concept of being is introduced into systematic theology. This was so in the earliest period of Christian theology and has been so in the whole history of Christian thought. It appears in the present system [meaning in his systematic theology] in three places, in the doctrine of God where God is called being as being or the ground and the power of being; in the doctrine of man…and in the doctrine of Christ where he is called manifestation of New Being…In spite of the fact that classical theology has always used the concept of “being” the term has been criticized from the standpoint of nominalistic philosophy and that of personalistic theology. Considering the prominent role which the concept plays in the system it is necessary to reply to the criticisms and at the same time to clarify the way in which the term is used in its different applications.

The criticism of the nominalists and their positivistic decedents to the present day is based upon the assumption that the concept of being represents the highest possible abstraction. It is understood as the gneus to which all other genera are subordinated with respect to universality and with respect to the degree of abstraction. If this were the way in which the concept of being is reached, nominalism could interpret it as it interprets all universals, namely, as communicative notions which point to particulars but have no reality of their own. Only the completely particular, the thing here and now, has reality. Universals are means of communication without any power of being. Being, as such, therefore, does not designate anything real. God, if he exists, exists as a particular and could be called the most individual of all beings.

The answer to this argument is that the concept of being does not have the character that nominalism attributed to it. It is not the highest abstraction, although it demands the ability of radical abstraction. It is the expression of the experience of being over against non-being. Therefore, it can be described as the power of being which resists non being. For this reason the medieval philosophers called being the basic transcendetntale, beyond the universal and the particular. In this sense was understood alike by such people as Parmenides in Greece and Shankara in India. In this sense its significance has been rediscovered by contemporary existentialists such as Heidegger and Marcle. The idea of being lies beyond the conflict of nominalism and realism. The same word, the emptiest of all concepts when taken as an abstraction, becomes the most meaningful of all concepts when it is understood as the power of being in everything that has being.[8]

Tillich tells us that the notion of God as being itself is old; it can be taken back to the pre-Socratics. It has been used throughout the history of the church. The two major criticisms are the idea that it is nothing but an empty abstraction and that is means an impersonal view of God. As will be seen both criticisms are false. The criticism that it is an empty abstraction is basically a reductionist criticism, going all the way back to the nominalists. In its modern incarnation it is a reductionist criticism. In refuting this argument Tillich implicitly denies that his concept of God is anything like an atheistic concept. He denies that his view is that the fact of existing things is God, or God is nothing more than the sheer fact of existence. The alternative to mere abstraction that Tillich offers is the “power of being.” By that he means being as an active force that resist nothingness. He almost makes it sound like nothingness is an active force, or like gravity, pulls us to the center of mass, or like water draining out of a sink. We are being sucked down the drain to the sewer of nothingness except the drain stopper of being prevents this. The transcendental transcends both universal and particular according to Tillich. In Platonic analogy that would give being itself the role of “the one” as the form of the forms. That’s probably somehow analogous to the role the idea played in Tillich’s understanding. What he says about the same word can be either the emptiest or the most meaningful of terms depending upon one’s assumptions, is actually a good fleshing out of what he means by being having depth. Not only is he saying that things are not as they seem on the surface, but one way in which they are not the same is that there’s a power to being that resists nothingness. Being is “on,” by that I mean it’s a positive force; it is the most basic thing aside from nothingness.

The quotation given above continues:

No philosophy can suppress the notion of being in this latter sense. It be hidden under presuppositions and reductive formulas, but it nevertheless underlies the basic concepts of philosophizing. For “being” remains the content, the mystery and the eternal aporia of thinking. No theology can suppress the notion of being as the power of being. One cannot separate them. In the moment in which one says that God is or that he has being, the question arises as to how his relation to being is understood. The only possible answer seems to be that God is being itself, the sense of the power of being, or of the power to conquer non being.[9]

At this point the terminology gets sloppy and hazy. Is God the power of being? Is being itself the power of being? Is being the power of being? If being is the “power of being.” This is a redundant phrase. What does “being is the power of being” tell us about what being is? Of course we can always sort it out in our own way and hope we are on the same page with Tillich. God is the power of being, but that would mean that God is also something other than being which furnishes being its power. Unless we want to say that Being is power. What is being? Power. What is power, being? What in the heck are we saying? The answer is that Tillich says himself this phase “God is being itself” is a metaphorical way of speaking. It’s a symbol, it’s not meant to be a literal and precise formation tracing the essence of the divine. We might also note that John MacQuarrie makes a distinction between Being and “the beings.” Contingent beings are “the beings” and they cohere in reality because they participate in Being as creatures of the Being itself.[10] Being is the power to resist nothingness, the power to be. Thus we can say God is the basis upon which all that is coheres and has its being. God is the basis upon which “the beings” (all existing things) have their being. The power of being is its nature to generate becoming. Just as existentialism presupposes an essential to play off of, so becoming presupposes state of Being to develop from. Yet, these statements must be taken as metaphors, as Tillich himself says. We cannot understand these terms as scientific style terms which accurately tell us the physical make up and dimensions of a given object. These are not ways to promote a scientific understanding of God, or could hey be nor should they be.

sources

[1] Paul Tillich, The Shaking of the Foundations. New York, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948.

[2] This was raised in a private discussion when one of my former professors was told I was working on this project.

[3] Paul Tillich, The Courage to Be. London and Glasgow: Collins, the Fontana Library, 1952-74.175

[4] Tillich, History, 247

[5] Ibid. [6] Ibid

[7] That is according to my friend Scott Gross who studied process theology at Claremont with Hartshorne, D.Z. Phillips.

[8] Paul Tillich, Systematic Theology volume II, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1957, 10-11.

[9] Ibid

[10] John MacQuarrie, Principles of Christian Theology, op cit (find where he says being and the beings)

feb 2010